Larry Scott knew he had a problem.

If he didn’t know it when he took the job in 2009, he certainly knew it when he brought in former NFL VP of Officiating Mike Pereira in 2011 to fix it. His referees sucked, to put it bluntly, and it was the one of the key obstacles in harnessing the growth potential of college football’s most promising conference.

When a crew of Pac-12 officials was given the chance to officiate the 2013 BCS National Championship Game, it had to give Scott the feeling of both delight (because of the shift in perception leading to the opportunity) and terror (because he knew they had the potential to screw up that opportunity.) His hope: that his officials could get through four quarters without vomiting on themselves and avoid making a call that could shift a national title.

Unfortunately, the Pac-12 officials couldn’t go four minutes without causing a major controversy, making highly questionable calls on a Notre Dame third down, and then on a mishandled punt by Alabama on the game’s next play. The calls took away two possessions for Notre Dame, Alabama jumped out to a 14-0 lead, all while social media lit up with incredulity across the nation amidst a wave of “told-you-so”s from Pac-12 fans.

Unfortunately, the Pac-12 officials couldn’t go four minutes without causing a major controversy, making highly questionable calls on a Notre Dame third down, and then on a mishandled punt by Alabama on the game’s next play. The calls took away two possessions for Notre Dame, Alabama jumped out to a 14-0 lead, all while social media lit up with incredulity across the nation amidst a wave of “told-you-so”s from Pac-12 fans.

Alabama would go on to throttle Notre Dame, leading 28-0 at halftime before winning 42-14. The blowout would largely absolve the Pac-12 officials’ earlier gaffes from the public narrative, the implication being, “Alabama may have gotten help, but they didn’t need it.” Potential crisis was averted; as the conference wouldn’t have to explain why its officials were responsible for deciding a title instead of the players and coaches.

Alabama would go on to throttle Notre Dame, leading 28-0 at halftime before winning 42-14. The blowout would largely absolve the Pac-12 officials’ earlier gaffes from the public narrative, the implication being, “Alabama may have gotten help, but they didn’t need it.” Potential crisis was averted; as the conference wouldn’t have to explain why its officials were responsible for deciding a title instead of the players and coaches.

There’s only one problem with that story: it’s only half true. The Pac-12 officials didn’t give Alabama the title that night in Miami; they gave it to them 51 days earlier in Eugene.

In the last three seasons, Oregon has won 90% of their games – 36 wins to only four losses. More impressively, of those 36 wins, only three were by fewer than 15 points (’10 Cal, ’12 Wisconsin, ’12 USC). During that span, Oregon had another seven wins where they were tied or trailing at the half, yet only one of those games (’12 Wisconsin) failed to produce a 15+ point victory.

With Chip Kelly gone and his narrative at Oregon completed, that will be how the Ducks under him will be remembered – losses, though few and far between, were still more likely than close wins, even if the team trailed in the second half. Simply put, games were either a blowout, or a loss.

The fulcrum of their success is the third quarter. Oregon’s gameplan involves doing the same thing over and over until that plan finds traction. Once it does, Oregon is scoring over 40, guaranteed. If it doesn’t happen, they’re scoring in the teens, and hoping the defense can hold on, like it did against Cal in 2010.

The intent of this analysis is to show the impact the officials had on the outcome of the 2012 Oregon-Stanford game: how their haphazard attempts to gain control of the game, a game which they lost grasp of early on, through ill-timed calls or no calls, had as much of an impact on the game as any other factor in preventing Oregon’s offense from its ability to gain traction. As Oregon attempted to hold on to a lead in the game’s waning moments, the officials directly impacted the end result by unnecessarily injecting themselves into the game’s outcome.

Unlike the National Championship, this time the Pac-12 officials we actually able to get through the first quarter without controversy, so let’s pick up the action early in the second, with 12:39 remaining.

Chip Kelly is upset, as we see the first sign of the officials losing control of the game. Following Stanford’s touchdown to put the Cardinal up 7-0, Kelly argued that Stanford should have been whistled for illegal man downfield.

Chip Kelly is upset, as we see the first sign of the officials losing control of the game. Following Stanford’s touchdown to put the Cardinal up 7-0, Kelly argued that Stanford should have been whistled for illegal man downfield.

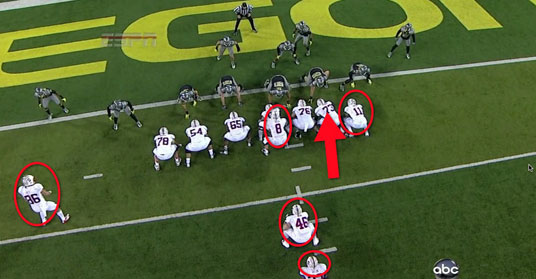

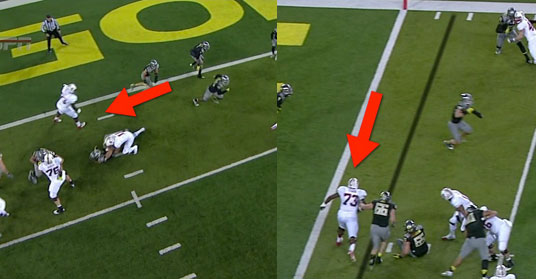

The rule for illegal man downfield dictates that the only eligible receivers (those allowed past the line of scrimmage) are those lined up behind the line of scrimmage (above), and the ends on either side of the line. All other players, including Stanford lineman Cameron Fleming (#73), are ineligible past the LOS, save for a one-yard cushion (the single yard provision is in place to minimize penalties), until the ball passes the line of scrimmage.

The rule for illegal man downfield dictates that the only eligible receivers (those allowed past the line of scrimmage) are those lined up behind the line of scrimmage (above), and the ends on either side of the line. All other players, including Stanford lineman Cameron Fleming (#73), are ineligible past the LOS, save for a one-yard cushion (the single yard provision is in place to minimize penalties), until the ball passes the line of scrimmage.

Was Chip right? While it’s uncertain if #73 is over a yard downfield, it’s very close (above), and Chip definitely has a case. Does the umpire hear him out? If by “hearing him out”, you mean, “gave him a 15-yard unsportsmanlike conduct penalty”, then yes.

Was Chip right? While it’s uncertain if #73 is over a yard downfield, it’s very close (above), and Chip definitely has a case. Does the umpire hear him out? If by “hearing him out”, you mean, “gave him a 15-yard unsportsmanlike conduct penalty”, then yes.

While giving a coach an unsportsmanlike conduct penalty for arguing a call is about as common as a one-point safety, the call itself set the trend for penalties that night. Every penalty called against the Ducks against Stanford resulted in one of three outcomes:

- Hindered field position at the start of a drive

- Negated an Oregon first down conversion

- Negated a successful Oregon third down defense

The unsportsmanlike call against Kelly following the touchdown allowed Stanford to kickoff from the 50, neutralizing Oregon’s dangerous kick returners on one of only three kick return opportunities (two TDs and the start of the second half) the Ducks would have the entire game. It was an unnecessary call, one driven by most by official’s desire to demonstrate his authority rather than operating from a position of control. As the game progressed, each call, or no call, carried increasingly detrimental weight towards Oregon’s chances.

As addressed earlier, establishing momentum in the third quarter is critical to Oregon’s success. Yet the greatest impact in momentum was made by the referees, whose officiating became more destructive with each successive possession.

The four possessions the Ducks had in the third quarter, with penalties and their drive outcomes:

- 15:00: No penalties called, drive ends in punt.

- 9:55: Personal foul/leg whip called on Bralon Addison. Wiped out Oregon first down. Drive ends in touchdown.

- 6:20: Holding called on Ryan Clanton. Wiped out Oregon first down. Pushes Oregon back to 1st and 20, forced to kick 42-yard field goal on fourth down. Kick is missed.

- 3:27: No penalties called despite obvious Stanford infractions on second and third down, drive ends in punt.

We’ll address the last three.

The drive beginning at 9:55, 3rd, though having an absurd leg whip call, followed by one of the most farcical sequences in college football last season, with the head linesman losing track of the down, then swaying the other officials, before being re-corrected (above); ultimately didn’t cost Oregon anything, as the Ducks ended the drive in a touchdown.

The drive beginning at 9:55, 3rd, though having an absurd leg whip call, followed by one of the most farcical sequences in college football last season, with the head linesman losing track of the down, then swaying the other officials, before being re-corrected (above); ultimately didn’t cost Oregon anything, as the Ducks ended the drive in a touchdown.

The detriment begins with the drive starting at 6:20. After shifting the momentum following the recovery of a Stanford fumble, Oregon picks up a first down two plays later. They picked up another first down, this time in the red zone, a 12-yard catch by Daryle Hawkins, which was immediately wiped out following a holding call. The call pushed Oregon back ten yards, leading to a 42-yard field goal. Given that it was largely understood publicly that forty yards was the edge of Oregon’s kickers’ range, it reasons that the call took points off the board.

Yet the damaging nature of that call pales in comparison to the hypocrisy we see from the officials on Oregon’s next drive, beginning at 3:27.

We can complain about the timing of the holding call, or its impact on the play, but by the nature of the officials’ role as rule-enforcers, that’s their prerogative. However, if the officials choose to enforce a game that closely, they must adhere to that strategy throughout the game. If they call close penalties on Oregon, it would reason they should do so on Stanford as well.

Which makes what occurred on second and third down of Oregon’s final drive of the third quarter an absolute travesty.

Oregon’s drive begins following a Stanford punt. On the punt coverage, the officials flagged Josh Huff for a personal foul (above), likely for hitting a Stanford player too far into the bench.

Oregon’s drive begins following a Stanford punt. On the punt coverage, the officials flagged Josh Huff for a personal foul (above), likely for hitting a Stanford player too far into the bench.

Now backed up an additional 15 yards, Oregon began its drive. Two plays later on 2nd and 10, Kenjon Barner ran to the right side, pushed out of bounds by Stanford CB Terrence Brown (#6). Brown continues to hold onto Barner, eventually tackling him three yards deep on the sideline in front of the line judge, with no call !

Now backed up an additional 15 yards, Oregon began its drive. Two plays later on 2nd and 10, Kenjon Barner ran to the right side, pushed out of bounds by Stanford CB Terrence Brown (#6). Brown continues to hold onto Barner, eventually tackling him three yards deep on the sideline in front of the line judge, with no call !

Brown wasn’t done with his run of impunity. Now 3rd-and-7 from the Oregon 12, not 1st-and-10 from the Oregon 27, Brown hits Will Murphy prematurely (above), which any average football fan could tell was pass interference; or as 59,000 average fans determined, as a cascade of boos echoed throughout Autzen Stadium during the entire change of possession.

Brown wasn’t done with his run of impunity. Now 3rd-and-7 from the Oregon 12, not 1st-and-10 from the Oregon 27, Brown hits Will Murphy prematurely (above), which any average football fan could tell was pass interference; or as 59,000 average fans determined, as a cascade of boos echoed throughout Autzen Stadium during the entire change of possession.

Oregon punted, and wouldn’t have a complete drive the remainder of the third quarter. The standard window for Oregon to gain traction had closed.

Like the game in Berkeley in 2010, eventually the tone of the game changed from “waiting for the offense to get going” to “hoping the defense could hold the lead”. Unfortunately, this didn’t happen.

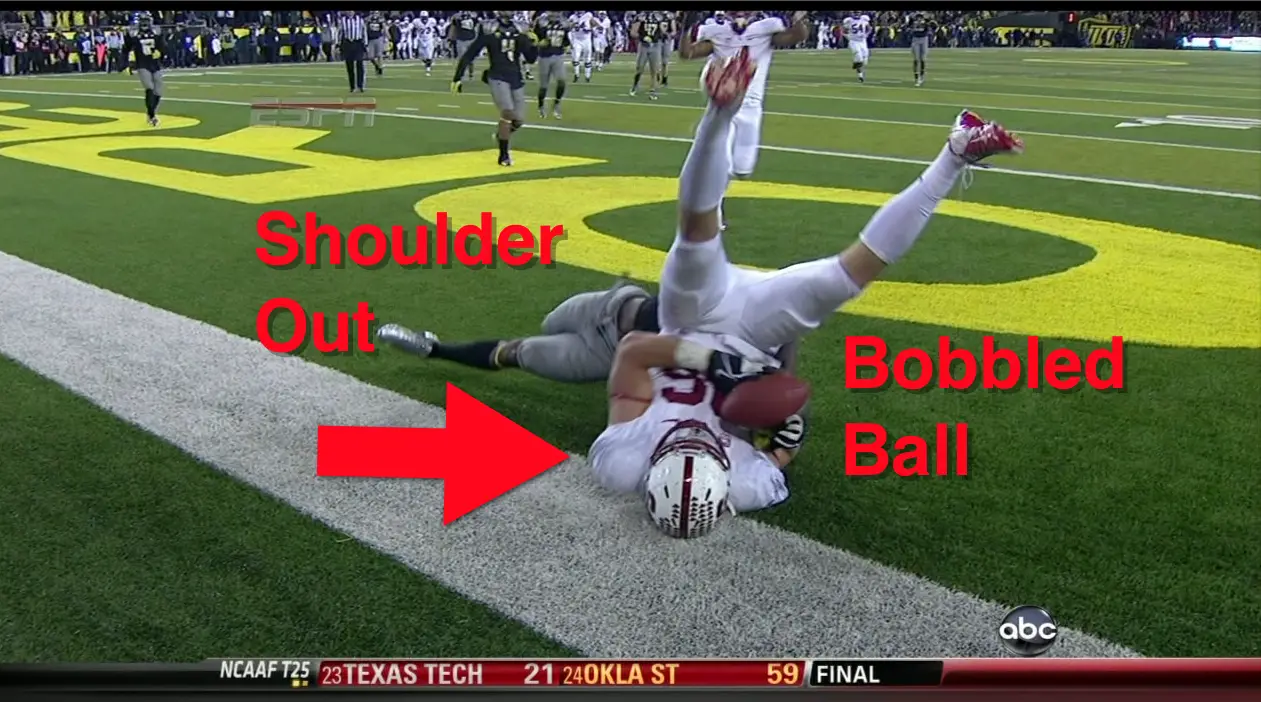

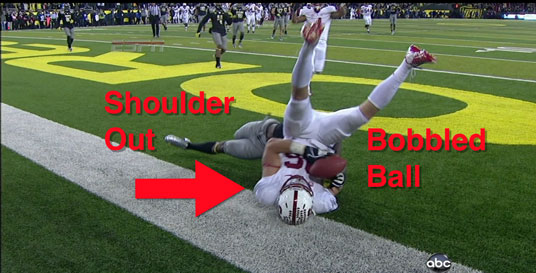

I’ll avoid devoting any more analysis to a single play that has already been dissected as though it were the Zapruder film, instead offering context as to how absurd this ruling was.

Here is what the NCAA rule book says about overturning a call:

SECTION 7, ARTICLE 1: Reversing an On-Field Ruling

To reverse an on-field ruling, the replay official must be convinced beyond all doubt by indisputable video evidence through one or more video replays provided to the monitor.

In that description, we see the egregiousness of the replay official’s ruling. His responsibility was not to determine whether the receiver made the catch; that difficult decision lay with the officials on the field. Instead, the replay official’s job is merely to observe the play; if there is any uncertainty whatsoever, the call on the field must be upheld. That’s it. He doesn’t have to do anything that challenges the scope of his abilities; he just has to not screw up. (How badly did he screw up? The man brought in to train him how to do his job wrote an article the following day describing how badly he screwed up.)

By injecting himself into the game, the replay official swayed the course of the 2012 college football season. Coupled with the decisions of the Notre Dame-Stanford officials five weeks earlier, and Pac-12 refs cost the conference two potential title game participants, and likely a National Championship. That success would have brought the conference and its teams millions, but that financial windfall has no value for the conference’s officials. They’ll be back in Pac-12 stadiums this fall, continuing to get paid no matter how badly they ruin things for their employer. When someone does their job that poorly and stays employed, they’re stealing a paycheck. It should come as no surprise their specialty is larceny, because they’ve already stolen a title from the Oregon Ducks.

Related Articles:

Nathan Roholt is a senior writer and managing editor emeritus for FishDuck. Follow him on Twitter @nathanroholt. Send questions/feedback/hatemail to nroholtfd@gmail.com.