In recent weeks, the $63 million expansion to Oregon’s Len Casanova Center has been in the news as construction has begun on the 130,000 square foot project.

Some attention has gone to the unique private-public partnership behind the deal, in which a Phil Knight-owned development company leases the university’s land in order to build there (without following university construction processes) and then hand the finished building back to the Oregon athletics department as a gift. Others have focused on the amenities the bigger, better Cas Center will bring Duck athletes, from a new 25,000 square foot weight room to enhanced video facilities and a new practice facility.

While the Cas Center expansion is indeed an important part of Oregon’s continuing quest to win a national championship through investing in state-of-the-art facilities to go with its innovative coaching staff, it will not mark the end of the school’s architectural ambitions. In fact, the truly landmark project may be one yet to be announced but long anticipated: an expansion to Autzen Stadium.

As Duck fans remember from a decade ago, construction crews first expanded Autzen between the 2001 and 2002 seasons, with the south half the stadium rebuilt to bring capacity from approximately 41,000 to 54,000 (although crowds have surpassed 60,000 with standing-room-only seating). Although the addition meant that Oregon now had crowds coming closer to some of the conference’s larger facilities such as Husky Stadium and USC’s Memorial Coliseum, having one half of the oval larger than the other ruptured the elegant symmetry of the original 1967 design by internationally renowned architecture firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (creators of the Sears Tower in Chicago and the new World Trade Center in New York).

Bowl-shaped stadiums such as Autzen, the Rose Bowl, Michigan Stadium and Notre Dame Stadium have long been considered the most special of stadium designs, recalling the symmetry and simple beauty of the original Roman Coliseum. An expansion would not only put Autzen right again in terms of its original form, but would also bring capacity up to some 70,000, and probably surpassing that figure with standing-room seating. When architecture firm Ellerbe Becket won the job to design Autzen’s 2002 expansion, they were the only firm to go beyond what the university asked for—designing a new south side—and offer a future design for a full expansion.

Expanding Autzen Stadium wouldn’t just be a matter of increasing capacity, however. It would be an architectural symbol seemingly meant to give a sense of solidity and permanence to the metamorphosis of the Oregon program into one of the nation’s most elites. The circa-2002 façade has already become an icon of sorts, with the “O” logo towering from above and the space beneath a series of Y-shaped columns providing a gathering place shaded from the elements.

After all, the original stadium, despite the elegance of its bowl-shaped design, was designed to fit into the landscape without towering over the surrounding city of mostly one to three-story buildings. A new addition to Autzen would give Oregon the opportunity to make a grand architectural statement. Sport, like the rest of history, is a quest for dominance and to build empires, be they benevolent ones or malicious. Autzen could, and assumedly would try to be, given some of the ambitious people behind any such expansion, an architectural landmark.

One can only guess what wonders a new stadium could include. What about a second awning, for example? Not only would it shelter more fans from inclement weather (although legend of course has it that it never rains at Autzen Stadium), but it would also help make the acoustics even noisier. As at Qwest Field in Seattle, known as one of the loudest stadiums in the National Football League, at an Autzen with two partially covered halves the sound of fans cheering would bounce off the awning and back over the field – like a 767 jet engine taking off.

If we’re talking about building a state-of-the-art stadium, the premier feature today is retractable roofs. It would make the cost much greater, but as how recent athletic-department projects such as the Casanova Center expansion, Matthew Knight Arena and the Jaqua Center for student-athlete academics, there is a willingness to commit the necessary budget for matchless architecture. A retractable roof stadium would be the first in Oregon, and would bring the opportunity to host a number of additional indoor events there.

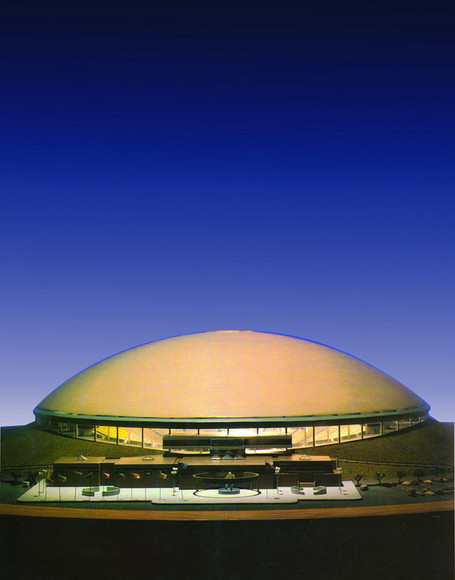

The model for the Duck Dome in 1986

Ultimately it seems doubtful Oregon would invest in a retractable roof for Autzen given that Matthew Knight Arena was just completed, and the weather is very rarely harsh enough in the autumn in Eugene to justify closing out the elements for a football game.

However, it should not be forgotten that for a time in the 1980s there was talk of making Autzen a domed stadium, with a wooden roof and skyboxes added to the original 1967 structure. Before the Moshofsky Center was constructed, then head coach Rich Brooks felt an indoor facility was needed to entice recruits to come to Oregon to escape the harsh winter conditions. A model of the wooden roof dome design still resides inside the Casanova Center.

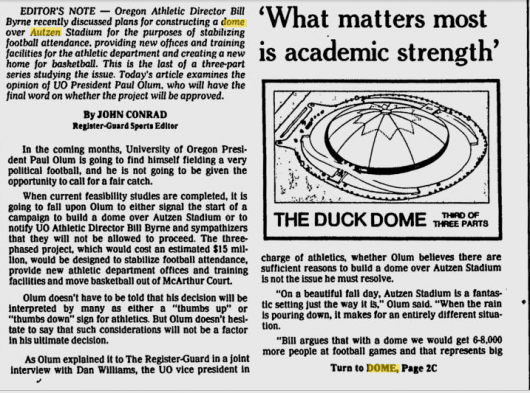

In 1986 a mock-up design was created for a potential dome to sit atop Autzen Stadium, spearheaded by Athletic Director Bill Byrne as a means to create skyboxes that could generate needed funds. In addition, with Mac Court showing its age it was proposed that a draped off Autzen could replace Mac Court hosting basketball games, much like Syracuse’s Carrier Dome and the Alamo Dome, home of the San Antonio Spurs. In the off-season Autzen could then double as a convention center of sorts.

Excerpt of a May 8th, 1985 Register Guard article detailing the plans for a dome over Autzen Stadium

While the bizarre “Duck Dome” idea thankfully died a quiet death, the failed attempt to modify Autzen led to alternate plans that proved far more successful, acquiring funding to construct the Autzen north side Sky Suites, which helped fund the building of the Casanova Center.

It should go without saying, of course, that all of this regarding a possible retractable roof or north side expansion is pure speculation. Maybe Autzen will stay in its current form for another 20 years. And as coach Chip Kelly’s apparent near departure for the NFL’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers reminds us—every team’s successful run is always a house of cards that could succumb to change at any moment, not always for the better. Even so, the “unfinished business” that Kelly referred to in deciding to stay at Oregon may be destined to bring even bigger moments than the glories of recent years. Certainly as sellout after sellout at Autzen has shown, there is clearly enough demand to justify another ten to fifteen thousand seats.

And after all: Oregon’s symbol, the “O” logo, is gorgeous and enduring in part because of the inherent beauty and simplicity of a perfect circle. Isn’t it fitting that the team’s home comes full-circle in its expansion too?

Related Articles:

Chip Kelly Update: Everything's Good Again ...

Chip Kelly Update: Wailing and Gnashing of Teeth

Shock and Awe -- The Oregon Ducks' Football Hangover Effect

Despite Lopsided Score, Georgia State "Never Stopped Believing"

Hope Springs Eternal for Ducks

Incompetent Pac-12 Officials: How Do You Miss ALL of THIS?

Brian Libby is a writer and photographer living in Portland. A life-long Ducks football fanatic who first visited Autzen Stadium at age eight, he is the author of two histories of UO football, “Tales From the Oregon Ducks Sideline” and “The University of Oregon Football Vault.” When not delving into all things Ducks, Brian works as a freelance journalist covering design, film and visual art for publications like The New York Times, Architect, and Dwell, among others.