The MVP of the Super Bowl last year was Eli Manning, the quarterback of the New York Giants. It was well deserved. Eli took a beating in the prior week’s game and in this one too but he held his composure and kept his football confidence and mental toughness in check and played a simply outstanding game. The vast majority of passes from Eli were right on target and gave the receivers a chance to catch the ball in-bounds for the Giants. He also scrambled and avoided many sacks or knock down. He simply rose to the occasion, used his sport psychology for football as well as his physical talents and played a simply outstanding Super Bowl game.

The Head Coach of the Giants, Tom Coughlin went to extraordinary measures to mentally prepare himself and his players for the Super Bowl. Among other things, he had the player’s participate in Yoga classes the week of the Super Bowl to get them to mentally focus on the game at hand. In regard to his own personal mental preparation as he states, “When you do get totally engrossed in the game, it’s not unlike any other game that you’re involved in. But really, you get into a zone and you don’t think about those things. You’re not paying attention to the vastness of the game, the importance of the game.” In other words, his football mentality was totally focused on each play as it was playing out.

David Tyree was another huge contributor to the New York Giants winning the Super Bowl this year. He prepares mentally in the off season for the next year by meeting with a football sport psychologist who helps him to see what he can improve on for next season. Tyree says they usually watch game tape and then the psychologist asks him what was going through Tyree’s mind at the time of the play. It’s a win-win situation.

If you watched the Super Bowl last year you can infer on your own that there is absolutely no question that the New York Giants were much more mentally prepared for the game and also they had a confidence because of this preparedness to be able to win the game; which they did.

Is there any doubt that this sounds like Chip Kelly and the Oregon Ducks? Fans often talk a lot about players’ skills and statistics, but show a lesser interest in and knowledge of what goes into being mentally prepared for a game.

‘Win the Day’ is a phrase that shows that a great deal of mental preparation must be happening in Chip Kelly’s entire approach to football and his players. The players’ performance, posture, attitude, workmanlike and confident approach to game preparation and game performance, speaks volumes about the genius of Kelly’s approach to winning.

Today, we will explore the role of anxiety and mental preparation in competitive sports and the accompanying theories that may explain anxiety’s role – the good, bad, and the ugly.

Sport is littered with the broken dreams of those who wavered when they most needed to be in control of themselves and focused on the task at hand. We will explore the nature of anxiety and its common symptoms, review the latest competition anxiety research, and provide you with five techniques that either control anxiety or channel it positively into your performance.

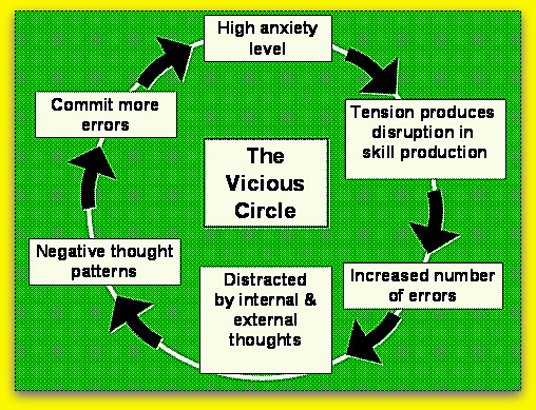

When a competitor ‘freezes’ in the big moment or commits an inexplicable error, anxiety, in one of its many guises, is very often the root cause. The precise impact of anxiety on sporting performance depends on how you interpret your world. Unfortunately, far too many athletes accept high levels of anxiety as an inevitable part of the total sporting experience and fail to reach their potential.

What Precisely is Anxiety?

Anxiety is a natural reaction to threats in the environment and part of the preparation for the ‘fight or flight’ response. This is our body’s primitive and automatic response that prepares it to ‘fight’ or ‘flee’ from perceived harm or attack. It is a ‘hardwired’ psychological, somatic, and physiological response that ensures survival of the human species (think adrenaline, for example). Sporting competition promotes similar psychological and bodily responses because there is often a threat posed towards the ego; your sense of self-esteem. Essentially, when the demands of training or competition exceed one’s perceived ability, anxiety is the inevitable outcome.

The Main Causes of Anxiety

At the same time as providing challenge and stimulation, sports also provide considerable uncertainty. At the precise moment the Olympic archer releases an arrow, or the placekicker kicks for a field goal, the outcome is unknown. The stress that sport provides therefore is inevitably linked with its inherent uncertainty. Sport is a cultural focal point because it is a theater of unpredictability.

While stress and uncertainty may motivate some athletes, they induce anxiety in others. There are some distinct factors that can increase athletes’ level of anxiety. For example, the more important the contest the greater the stress, and the more likely it is that a competitor will be prone to anxiety.

Also, spectators can have a huge impact on how athletes feel. In fact, studies of the home advantage phenomenon show that teams playing at their home venue win on average, around 56-64% of the time, depending on the sport. The impressive medal count of host nations during Olympic Games is also notable, in particular the record-breaking haul of medals won by Australia in Sydney (2000), by Greece in Athens (2004), and in the UK (2012).

Participants in individual sports have been shown generally to suffer more anxiety before, during and after competition than participants in team sports. This is because the sense of isolation and exposure is much greater in sports such as triathlon, golf, tennis and snooker than in the relative anonymity of field sports.

For athletes in high-contact sports such as football, basketball, boxing and martial arts, the possibility of getting hurt can also be a source of anxiety. Typically, this anxiety causes some critical changes in technique. For example, anxious boxers will often lean too far forward, be clumsy in their leg movements or fight defensively, any of which may result in them getting knocked out. Anxious linemen may be more prone to penalties because the anxiety makes it harder to control their own physical reactions.

An additional factor that causes anxiety is the expectation of success. The expectations held by British tennis fans for Tim Henman and Greg Rusedski to win the men’s singles title at Wimbledon have hung over these players like a dark cloud. Some athletes rise to the challenge imposed by public expectation while others can choke

Sport places a wide variety of stressors upon participants; it can be physically exhausting, it pitches one against superior opponents, hostile fans might verbally abuse the player, the elements may need to be overcome and one’s own emotional frailties are constantly laid bare for all to see. Despite this, sport offers participants an opportunity for growth and a chance to push back personal boundaries, and a means by which to liberate the body and the mind.

The Symptoms of Anxiety

Anxiety can be recognized on three levels:

On the cognitive level (relating to intellectual faculties of knowing, thinking or perceiving – e.g., by particular thought processes);

On the somatic level (bodily) – e.g., by physical responses;

On the behavioral level – e.g., by certain patterns of behavior.

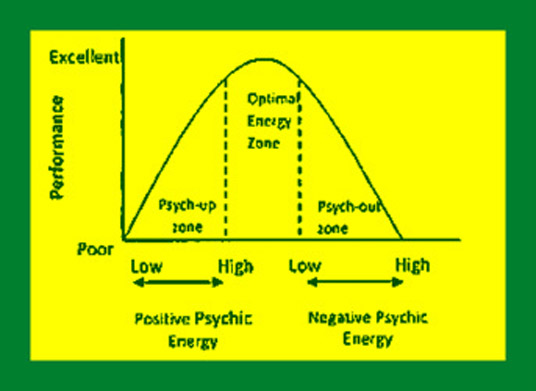

Table 1 lists some of the symptoms on each level. The reader might use this as a reference for recognizing anxiety. Not all of the responses are a cause for concern; increases in heart rate, respiration and adrenaline production can be very positive influences on performance, but the appearance of further somatic symptoms, and the emergence of the cognitive responses listed, means that excitement has turned to anxiety and appropriate anxiety control techniques may need to be applied. The trick is to become sufficiently ‘psyched-up’ without becoming ‘psyched-out’.

|

|||||||||||

Control Model of Competition Anxiety

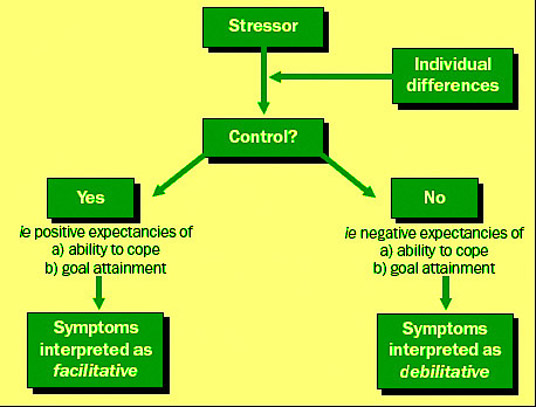

The extent to which we expect to control various competition stressors depends on factors that are specific to individuals, such as their personality, upbringing, experiences and trait anxiety – the degree to which individuals are predisposed to feel anxious. These are known as individual differences because they are the factors that serve to make each of us unique. In this model, individual differences mediate the relationship between a stressor and one’s perception of control.

The propositions of this model have generally been supported in the literature. One of the most recent studies examined the intensity and direction of anxiety as a function of goal attainment expectation and competition goal orientation. The intensity of anxiety is how much anxiety one feels, whereas direction has to do with whether they interpret the symptoms as being facilitative or debilitative to performance.

Team sport players who reported positive expectations of goal achievement and indicated some input into the goal generation process experienced the most facilitative interpretations of anxiety symptoms. The implications of this study are that athletes should set their own goals rather than have goals imposed upon them by a coach or team manager.

Research has shown that coaches and team managers may, however, have a key role to play in buffering the effects of anxiety. When researchers examined the influence of perceived coach support on anxiety among high school tennis players, their results indicated that for players who were predisposed to feeling anxious (trait anxious), the perceived support of their coach tempered their anxiety and helped them to cope far better with the psychological demands of competition.

Very recent work has examined the impact of motivational climate on young athletes’ anxiety. The results showed that coaches who promoted a mastery climate – one in which personal skill development was emphasized rather than superiority over peers (performance climate) – enabled their athletes to experience a significant decrease in anxiety from pre-season to late-season. This was in contrast to the anxiety of a control group of athletes, which increased over the season.

Ostensibly, there is nothing damaging about the stress associated with a sporting contest, and in fact stress can be a very positive influence that leads us to tackle the challenges that make life far more rewarding. However, when we perceive stress to be negative, it causes anxiety and therefore, much depends upon how we view the demands placed upon us.

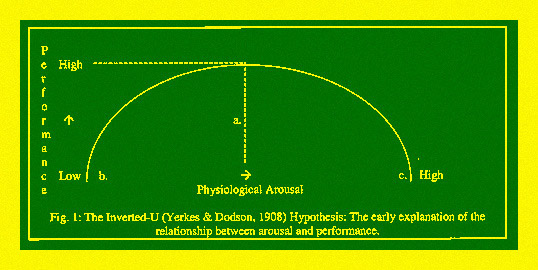

Originally, it was widely believed that the connection between performance and arousal was an uncomplicated Inverted-U. The best performance could be achieved with an average level of arousal.

Moreover, if the level of arousal were too low (or too high) poor performance would ensue. However, the Inverted-U Hypothesis (see Figure 5) was seen by some as being far too simplistic, and a number of researchers began to question its validity.

The Multidimensional Theory of Anxiety and the Catastrophe Model are the two foremost theories that have emerged in recent years. Despite offering a much-improved explanation of the ‘underlying mechanics’ of competitive anxiety, both descriptions are fundamentally in conflict with each other, and are not devoid of their respective critics.

Multidimensional Theory of Anxiety

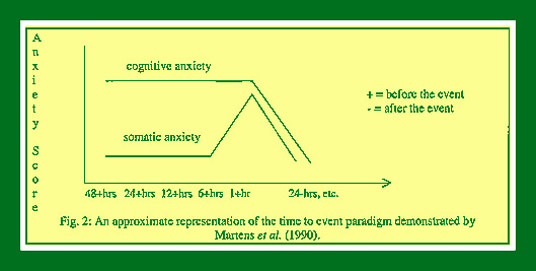

Primarily, the theory is based on the assumption that competitive anxiety is comprised of two distinct parts; a cognitive component, and a somatic component, both having dissimilar effects on performance. Hence, theoretically, the components can be manipulated independently of one another. The cognitive component has been defined as the negative expectations and concerns about one’s ability to perform and the possible consequences of failure. Whereas, the somatic component is the physiological effects of the anxiety experience, such as an increase in autonomic arousal with negative physiological effects, like palpitations, tense muscles, shortness of breath, clammy hands, and in some cases even nausea.

Researchers proposed that somatic anxiety had an Inverted-U shaped relationship with performance, whilst cognitive anxiety had a negative linear relationship with performance. In addition, they utilized a time-to-event paradigm to assist in the demonstration of the disconnection of somatic and cognitive anxiety. They affirmed that the cognitive component stayed stable before the start of the measurements before an event begins, but the somatic component began to increase prior to the onset of the event (see fig. 6 below). They found a relationship between the two sub-components to such an extent that there were positive effects related to cognitive anxiety in the days before a crucial event when somatic anxiety was at a low level. In addition, they found a combination of both negative and positive effects for somatic anxiety for a range of performance related activities shortly before the crucial event when cognitive anxiety was at an elevated level.

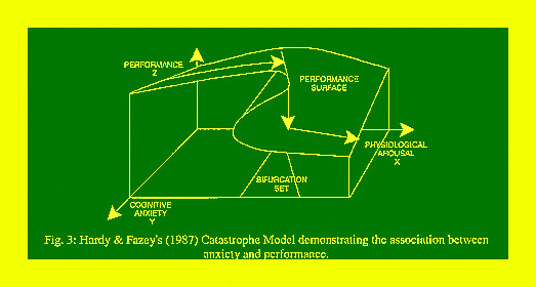

Catastrophe Model of Anxiety

The use of the expression ‘Catastrophe Theory’ was first conceived by the French mathematician Rene Thom in 1975 to describe a method that could model discontinuities in functions that was, as a rule, continuous. As is explained, Thom’s central theorem was that, with certain qualifications, all naturally occurring discontinuities could be classified as being of the ‘same type’ as (i.e., topologically equivalent to) one of seven fundamental catastrophes”.

A year later another researcher took the conceptual framework of catastrophe a step further by drawing attention to its potential relevance and utilization within the behavioral sciences. With the aid of a tangible model, he demonstrated the effectiveness of the cusp catastrophe, leading the way for others to implement catastrophe models to the appropriate behavioral sciences.

This model is not unlike the Multidimensional Theory of Anxiety as it presupposes that anxiety is comprised of two sub-components. In contrast however, rather than using somatic anxiety as the asymmetry factor, this model chooses to use physiological arousal. When measured by heart rate, both follow identical temporal patterns to, for example, a critical competitive event. Nevertheless, there are a number of differences between the two in relation to their effect on performance. It has been reasoned that physiological arousal may have a direct effect upon performance through the suppression of crucial cognitive and physiological resources. Additionally, physiological arousal (it is well known that physiological arousal can make anxiety worse) may also cause an athlete to interpret their physiological state as either negative or positive, inadvertently altering their performance. Somatic anxiety, on the other hand, is believed to effect performance only if the extent of the somatic response is so large that the athlete becomes excessively concerned and distracted with their perceived physiological state.

Physiological arousal follows the Inverted-U hypothesis in relation to performance. Nevertheless, that will only occur when the individual is exhibiting low cognitive state anxiety, (e.g. they are not worried about their immediate performance – see back face of fig. 3).

Alternatively, a catastrophe will occur if the individual is exhibiting high cognitive anxiety (e.g. concern over their immediate performance). This is typified by an increase in physiological arousal that will reach a threshold point just over the cusp of optimal arousal. Thereafter follows a steep and expeditious deterioration in the individual’s performance, (i.e., a catastrophe (see right face fig. 4). It was further proposed that cognitive anxiety behaves as a splitting factor that causes the normal factor’s (i.e. physiological arousal) effect on performance to be smooth and small, large and catastrophic, or alternatively falling somewhere within the two extremes. The model also predicts that if there is low physiological arousal present in the days leading up to an important event, cognitive anxiety will enhance the athlete’s performance in relation to the baseline data that can be taken from his training session (see left face, fig. 3). Additionally, one can state that the model will predict either positive or negative effects of physiological arousal upon performance when there is an elevation in cognitive anxiety. This depends upon how high the cognitive anxiety is at the time. This can be demonstrated by bisecting through fig. 7, parallel to the physiological arousal by performance plane.

There are three additional proposals based upon their model:

Physiological arousal should (for the most part) only be deleterious to athletic performance when there is high cognitive anxiety.

Hysteresis will follow when high cognitive anxiety is present, and a bifurcation set will arise, (i.e., the association of the same level of physiological arousal with two alternate levels of performance subject to the decrease, or increase, of the physiological arousal). To elucidate, it is predicted that there will be a negative correlation between performance and cognitive anxiety when physiological arousal is high, and a positive correlation when physiological arousal is low.

An average level of performance is unlikely to occur when high cognitive anxiety is present. Moreover, performance is likely to follow two distinct modes under conditions of high anxiety, as opposed to being unimodal when cognitive anxiety is low.

It should be stressed that the surface of the cusp catastrophe is ‘tailored’ to each individual, insofar as the model can be bent, stretched, rotated and transformed to fit an athlete’s ability and experience in relation to their performance. Notably, and central to the original theorem, the flexible properties of the cusp catastrophe can never be torn, (i.e., it should always remain continuous), following the fundamental rule of hysteresis, and the discontinuous changes in performance under certain conditions.

This relatively new catastrophe model is still in its ‘infancy’. Moreover, it has yet to evolve from its conceptual framework stage to a fully established and accepted theory. This, however, may not occur for some time as there is still very little current or on-going research involving the model to sufficiently validate its proposed explanation of A-state competitive anxiety. Additionally, this situation has been exasperated by the difficulty in testing the model.

Finally, despite its shortcomings, this approach has been regarded by many as a plausible ‘up to date’ alternative to the outmoded multidimensional theory. Nevertheless, the multidimensional theory has been invaluable in leading the way towards the identification and establishment of cognitive and somatic anxiety/physiological arousal as two distinct sub-components of A-state.

Five Techniques that Might Help Control Competition Anxiety

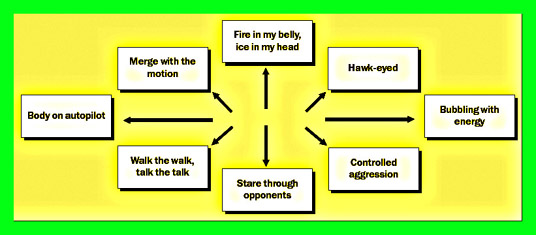

When mentally prepared, one should feel like this:

- You feel relaxed although the adrenaline level is high.

- A little nervousness but with a sense of calmness and confidence

- Your decisions will be made spontaneously without conscious thought process as you will have a strong belief in your ability.

- You will always feel as if you are in the right place at the right time

- You will maintain concentration and have an awareness of what is happening around you

- You will maintain control over your emotions and not become tense, therefore remain in total control of yourself

How does one get there?

To reach an optimum psychological state, an athlete needs to understand his/her own natural responses to stress and be sensitive to bodily signals. Learning to handle the demands of competition involves learning to read thought patterns and physical responses, and to develop the skills necessary to find one’s own ideal arousal level. Stress management requires excellent self-awareness because, if a person knows one’s self well, you will better understand the roots of your anxiety.

We will begin by outlining a self-awareness technique that allows someone to ‘capture in a bottle’ the feelings associated with success – ‘the winning feeling’. We will then look at the popular ‘centering’ exercise which relieves tension through focusing attention to the center of the body. Following this, the ‘five breath technique’ will be described; an ideal prelude to competition for over-anxious athletes. The penultimate exercise is ‘thought-stopping’ which deals with the cognitive symptoms of anxiety such as negative thoughts and images. Finally, ‘letting go’ will be presented – the deepest relaxation exercise of the five and ideal for the night before competition.

Establishing a ‘Winning Feeling’

Reproduce figure 8 on a piece of paper but leave the boxes blank. Think carefully about the last time you were performing at the top of your game then list every detail you might associate with your ‘winning feeling’. Pick out the eight most important aspects of this positive feeling and write them neatly into the boxes. The example provided in figure 5 came from a female basketball player. You can use your winning feeling to help create an optimum competition mindset through consciously reproducing the desired elements.

Centering

The second technique is known as ‘centering’ because it involves focusing attention on the center of your body, the area just behind your navel (the ‘gut’ is an important organ in emotion, including anxiety). This is a technique that is particularly effective during sports that have breaks in the action, such as in between sets in tennis, or in changing from offense-to-defense-to-offense in football. Centering has a calming and controlling effect, providing a simple but effective way to counteract the negative effects of anxiety:

Stand with your feet flat on the ground, shoulder width apart, arms hanging loosely either side of your body;

Close your eyes and breathe evenly. Notice that when you breathe in, the tension in your upper body increases, but as you breathe out, there is a calmer, sinking feeling;

Inhale deeply from your abdomen and, as you do, be aware of the tension in your face, and your neck, and your shoulders, and your chest. As you exhale, let the tension fall away and focus on the feeling of heaviness in your stomach;

Continue to breathe evenly, focusing all your attention internally on the area immediately behind your navel;

Maintain your attention on that spot and breathe normally, feeling very controlled and heavy and calm;

On each out-breath use a word that encapsulates the physical feelings and mental focus that you want such as ‘loose’, ‘calm’, ‘focused’, ‘sharp’, ‘strong’, etc.

The Five-Breath Technique

This anxiety control exercise can be performed while you are standing up, lying down or sitting upright. It is ideally used just before competition, or whenever you feel particularly tense. You should inhale slowly, deeply and evenly through your nose, and exhale gently through your mouth as though flickering, but not extinguishing, the flame of a candle:

Take a deep breath. Allow your face and neck to relax as you breathe out;

Take a second deep breath. Allow your shoulders and arms to relax as you breathe out;

Take a third deep breath. Allow your chest, stomach and back to relax as you breathe out;

Take a fourth deep breath. Allow your legs and feet to relax as you breathe out;

Take a fifth deep breath. Allow your whole body to relax as you breathe out;

Continue to breathe deeply for as long as you need to, and each time you breathe out say the word ‘relax’ in your mind’s ear.

Thought-Stopping

When you experience a negative or unwanted thought (cognitive anxiety) such as ‘I just don’t want to be here today’ or ‘She beat me by five meters last time out’, picture a large red stop sign in your mind’s eye. Hold this image for a few seconds then allow it to fade away along with the thought. If you wish, you can follow this with a positive self-statement such as ‘I am going to hit it hard right from the start!’ Thought-stopping can be used to block an unwanted thought before it escalates or disrupts performance. The technique can help to create a sharp refocus of attention keeping you engrossed in the task at hand.

Letting Go

You will need to lie down somewhere comfortable where you are unlikely to be disturbed. If you wish, you can also use this exercise to aid a restful night’s sleep. Allow your eyes to close and let your attention wander slowly over each part of your body – starting from the tips of your toes and working up to the top of your head. As you focus on each part of the body, tense the associated muscles for a count of five and then ‘let go’. If this does not relieve the tension in a particular body part, repeat the process as many times as you need to. Once you have covered each body part, tense the entire body, hold for five and then ‘let go’. You will feel tranquil and deeply relaxed.

Benson’s Relaxation Response

Benson’s technique is a form of meditation that can be used to attain quite a deep sense of relaxation and can be ideal for staying calm in between rounds of a competition. It can be mastered with just a few weeks’ practice and comprises of seven easy steps:

Sit in a comfortable position and adopt a relaxed posture;

Pick a short focus word that has significant meaning for you and that you associate with relaxation (e.g., relax, smooth, calm, easy, float, etc.);

Slowly close your eyes;

Relax all the muscles in your body;

Breathe smoothly and naturally, repeating the focus word;

Be passive so that if other thoughts enter your mind, dismiss them with, ‘Oh well’ and calmly return to the focus word – don’t concern yourself with how the process is going;

Continue this for 10-15 minutes as required.

Conclusions

The key, then, to the best athletic performance depends on the proper regulation of anxiety (remember that it is both beneficial and debilitating depending on whether there is too much, just right, or too little). This is what mental preparation is all about: finding the best amount of anxiety that fits the circumstances. This means that not only is preparation for the game important, but also preparation for changing circumstances.

‘Win the Day’ is more than just about games; it is about practice, mental preparation each and every day, courage, confidence based on much more than self-esteem alone. The most self-esteemed people in our society are narcissists, and for the most part, they ultimately fail at life as well as eventually in sports (this is a generalization, but holds true most of the time).

The acquisition and the honing of skills towards perfection is an important feature of mental preparation, and include practice time. Self-confidence built on this is also useful to the control of anxiety at appropriate levels.

The Ducks have exceptional athletes with high-level performance abilities. Chip and the coaches’ game-planning and execution of it are brilliant, and the players’ performance of their responsibilities on each and every play are also dazzling, it all depends in the end on proper mental preparation and conditioning (mental, that is). Physical training, diet, medical and training care, and support of each player according to his needs are also important factors.

It is my professional view, and also my perspective as an observant fan, that the Ducks have few, if any, equals in this area.

Who do you think was the better prepared QB?

It appears that one of Marcus Mariota’s abundant good points is his mental preparation. That he does not panic, and that he played efficiently with few mistakes as a redshirt freshman, suggests that he is a young man who is mentally prepared to play like he does. How much is his nature, and how much he works on, is impossible to say at this distance. However, that he is prepared is undeniable.

It should also be clear to those of us that do not play high-level competitive sports, that mental preparation can improve our job performance and the accomplishment of all of our responsibilities at home, as well. The principles that define mental preparation can help with being a spouse, parent, coach, boss, or teacher.

Try using Figure 6 to analyze your mental state when you are at your best. Then try to get those feelings and thoughts when doing your job and when dealing with other circumstances.

To the many of us who play golf: use the information we have discussed consistently, and I promise that your game will improve (and if it should not, you will still get more pleasure from the game you have)!

Related Articles:

NeuroDocDuck (Dr. Driesen) is a doctor who specializes in neurology, and sports medicine. He is an Oregon alumnus, completing his medical education and training in the UK. He has been both a practicing clinician and professor, a well-known and respected diagnostician, an author, and has appeared on national television.

NeuroDocDuck is active in his profession, and stays current on all new trends in his field. He enjoys golf and loves his Ducks!