(FishDuck Note: This article holds astounding news for many of us “greybeards” who contend with knee problems as we age. Our own “NeuroDocDuck,” in the personage of Dr. Jacob Driesen, is writing for us to help us learn about sports injuries AND the proper treatments. This contribution could impact how the UO looks at knee injuries in the future!)

We hear the injury news all the time: “Player X requires arthroscopic surgery, out 4-6 weeks.” It’s a fairly common procedure in the world of sports, and we even see it in the news concerning athletes at the University of Oregon. However new research from Finland suggests that thousands of people who have arthroscopic knee surgery to fix a torn cartilage might be wasting their time, and the ripples of this research can reach across the world and alter how such injuries are treated in the Hatfield-Dowlin Complex in Eugene, Oregon.

A report on the Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY), published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, finds that the benefits of routine keyhole operations to repair degenerative meniscal tears are no better than a sham. Previous studies have shown that keyhole surgery on the knee does not help patients with osteoarthritis and, as such, those procedures have become less common for arthritis sufferers. In the meantime, typical keyhole surgery to repair torn cartilage has risen significantly, despite lack of evidence that it actually helps, says the Finnish team.

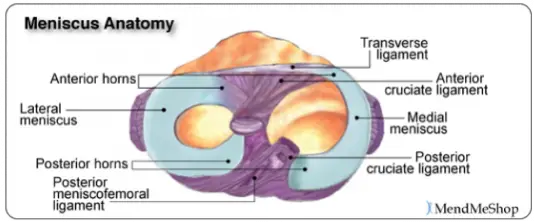

Knee problems, other than arthritis that cause stiffness and pain, are very common and are caused most often by gradual wear and tear rather than sudden injury or trauma. The most common diagnosis that requires treatment is a torn meniscus, a crescent-shaped cartilage that acts like a shock absorber that helps stabilize the knee.

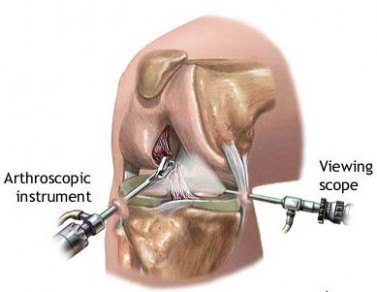

The usual procedure for repairing a torn meniscus is keyhole surgery or arthroscopy, where the surgeon inserts a scope through a small incision to examine the joint and, if required, also partially removes the damaged cartilage through another incision.

Comparing partial removal of damaged cartilage with a sham procedure

In this new study, the Finnish team recruited 146 patients aged 35 to 65 with meniscal tears that had developed through wear and tear, rather than injury or trauma. None of the patients had arthritis of the knee.

The researchers randomly assigned the patients to one of two groups: one who underwent the common keyhole surgery to remove partially the damaged meniscus and the other who underwent a sham procedure where nothing was actually done.

In the sham procedure, the surgeons simulated the real operation. They manipulated the patient’s knee and handled surgical instruments near the knee so the patient was under the impression they were being operated on. Consequently, both groups underwent arthroscopy, where the scope is inserted into the keyhole so the surgeon can look at the torn cartilage, but only one group actually had part of the cartilage removed.

However, neither the patients, the people caring for them after the operation nor the researchers analyzing the results, knew which patients had undergone the real procedure and which had just had the sham operation.

Both groups of patients were equally satisfied with the results!

The results show that a year later, both groups of patients had an equally low rate of symptoms and were equally satisfied with the overall situation of their knee. Both groups of patients said they believed their knee felt better than before the operation. When asked if they would choose the same procedure again, 93% of the partial meniscectomy group said they would, as did 96% of the sham procedure group.

The researchers concluded:

In this trial involving patients without knee osteoarthritis, but with symptoms of a degenerative medial meniscus tear, the outcomes after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy were no better than those after a sham surgical procedure (essentially a ‘placebo’).

Doctor talking to senior man in surgery.

Speaking of the impact the study is likely to have, lead author Raine Sihvonen, a specialist in orthopedics and traumatology at Hatanpää Hospital in Tampere in southern Finland, says: “It’s difficult to imagine that such a clear result would result in no changes to treatment practices.” He explains that in nearly all Western countries, this operation is now the most common surgical procedure after cataract surgery, adding that: “By ceasing the procedures which have proven ineffective, we would avoid performing 10,000 useless surgeries every year in Finland alone.

The corresponding figure for the US is at least 500,000 surgeries.”

Co-author and state adjunct professor Teppo Järvinen, of the Helsinki University Central Hospital, says: “Based on these results, we should question the current line of treatment according to which patients with knee pain attributed to a degenerative meniscus tear are treated with partial removal of the meniscus, as it seems clear that instead of surgery, the treatment of such patients should hinge on exercise and rehabilitation.”

While one study does not necessarily prove anything conclusively, and more studies are necessary, any patient with meniscal degeneration or tears should discuss this with his orthopedic surgeon before going ahead with surgery. This study gives us pause as only the expert on the scene can objectively judge the circumstances and give the best advice.

Related Articles:

Chip Kelly Update: Everything's Good Again ...

Chip Kelly Update: Wailing and Gnashing of Teeth

Shock and Awe -- The Oregon Ducks' Football Hangover Effect

Despite Lopsided Score, Georgia State "Never Stopped Believing"

Hope Springs Eternal for Ducks

Incompetent Pac-12 Officials: How Do You Miss ALL of THIS?

NeuroDocDuck (Dr. Driesen) is a doctor who specializes in neurology, and sports medicine. He is an Oregon alumnus, completing his medical education and training in the UK. He has been both a practicing clinician and professor, a well-known and respected diagnostician, an author, and has appeared on national television.

NeuroDocDuck is active in his profession, and stays current on all new trends in his field. He enjoys golf and loves his Ducks!