When the Ducks travelled south to play Pac-12 rival Stanford, there were predictions of a Duck victory. De’Anthony Thomas predicted the Oregon offense would put up forty points, and many others had Oregon at least securing the W. Vegas even had the Ducks as a 10+ point favorite. The Duck faithful had high hopes, and with good reason.

Leading up to the game, Oregon was ranked No. 3 in the nation and had been stellar offensively. In their first eight games the Ducks had 59 offensive touchdowns, 41 of which occurred in two-minutes or less, and were averaging more than 600 yards of offense per game. Most of us wondered how the Cardinal defense could hope to stop, or even slow down, Oregon’s dynamic offense.

Then it happened. Stanford was able to hold the mighty Duck offense to only two offensive touchdowns and just over 300 yards of total offense. Another painful loss to Stanford.

With the disappointments of the 2013 season now fading away to the renewed hopes and excitement of the upcoming 2014 season, it is a good time to engage in some self-reflection. Self-study, while usually somewhat painful, is a vital component for improvement. So with this in mind, let’s explore how Stanford’s offense was able to control the game tempo and keep the Duck offense on the sideline by consistently and effectively converting on 3rd down.

So … What Happened?

It is important to keep in mind that losses can rarely be explained by any single factor. The game of football is complicated, with many moving parts. As such, any number of things can be discussed and may vary depending on perspective.

To be sure, many of the usual suspects of a loss were present – turnovers, missed opportunities in the Red Zone and a good opponent. These factors were discussed previously by FishDuck here, and each contributed to the loss. Let’s look deeper, and explore some of the other statistics of the game.

Offensive football relies on an understanding what the defense is trying to accomplish, establishing a gameplan, and adjusting as necessary during the game. This is even more critical against quality opponents and often requires several possessions to understand how to most effectively counter what the defense is doing. In light of this, some of the following statistics offer up some valuable insight into why the Ducks were so uncharacteristically limited on offense:

- Time of Posession (TOP) — Oregon had the ball for just over 17 minutes, while Stanford controlled the clock for more than 42 minutes. In fact, Oregon only had the ball only once in the entire second quarter.

- Tempo Control — Stanford ran the ball for 274 yards on 66 carries, which shortened the game.

- The Cardinal converted 14-of-21 3rd down opportunities, which led to extended drives and the discrepency in TOP.

Stanford’s Favorite 3rd Down Concept

To accomplish this tempo and clock control, Stanford often turns to a power concept on 3rd down. This allows them to convert and maintain possession of the ball. Stanford will run this concept out of numerous formations, personnel sets, and may or may not pull linemen. The idea, however, is the same and is known as “power football.”

The basics involve getting a series of severe angle downblocks and/or double teams at the point of attack, while leaving the edge player initially unblocked. You then insert a player, sometimes a fullback, tight end, or pulling lineman, to kick out the isolated defender.

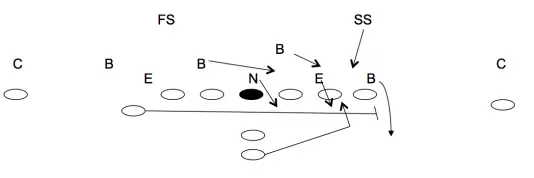

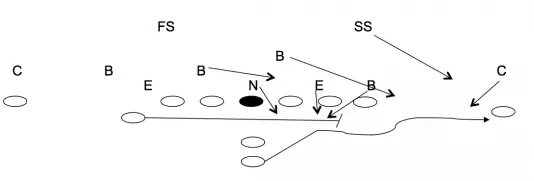

In this first example of a power concept, Stanford uses a 2×2 set and inserts the backside tight end across the formation for the kick-out block.

In this second example, Stanford is in a formation that utilizes eight offensive lineman. Again, there are severe angles and double teams at the point of attack, and a kick-out block on the edge defender.

The video above provides some great detail on how Stanford uses the power game.

Breaking Down the Power Concept

Let’s take a look at how Stanford used the power concept against Oregon on a key 3rd down in the first quarter.

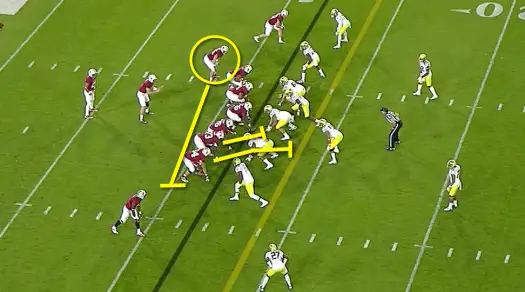

In the screen shot above, we have Stanford aligned in a 2×2 Gun formation with a single back. Note the backside wing player circled above. On the snap of the ball, we will see down blocks at the point of attack, and the wing player will cross the formation to kick out the edge player.

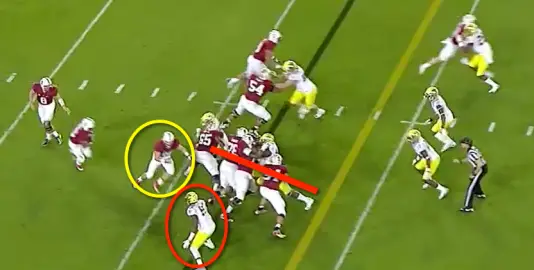

As the play develops, we can see (above) that the down blocks have created a wall, effectively sealing off the interior of the defense. We can also see the wing player, circled in yellow, closing in on the edge defender for the kick-out block.

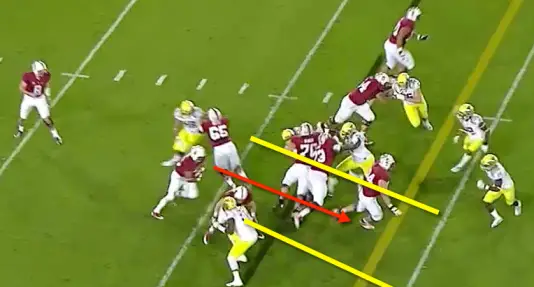

As the kick out occurs (see image above), the running lane develops, and the running back is able to gain the yardage needed to convert the third down and extend the drive.

Viewing the entire clip (above), we see that the running back is able to get down hill quickly and gain positive yardage.

Two Philosophies of Defense

There are two basic defensive philosophies that dictate how the defense will respond to the power game. One is the Contain Philosophy which is based on the idea of “setting the edge” and turning the ball carrier back inside to the interior of the defense. The other is the Spill Philosophy, which is predicated on continually forcing the ball carrier to bounce to the outside where, hopefully, a force player will be in position to make a play.

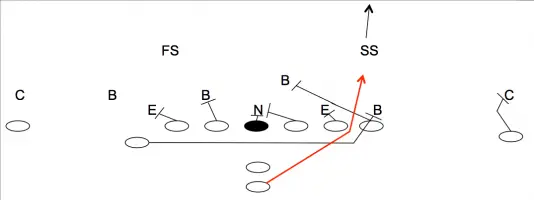

The diagram above illustrates the basic idea behind the contain philosophy. In this concept, the defensive edge player attacks the kick-out block with a goal of keeping his outside arm free and setting the edge. If done properly, this will turn the ball carrier back inside to other defenders.

This concept is effective against perimeter plays such as toss and sweep, but can be problematic against the power game because the play is designed to run the ball inside. The power concept takes advantage of the contain philosophy and uses it’s characteristics to create the running lane illustrated above in the screenshots. As shown, the interior of the defense is walled off by the down blocks and double teams and the kick-out block creates the running lane.

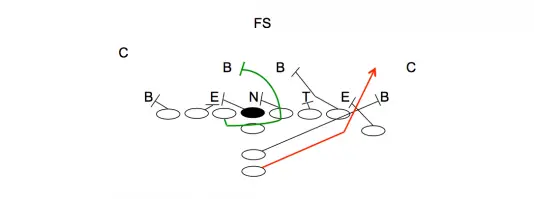

The second diagram (above) illustrates the spill philosophy. In this concept, the edge player again wants to attack the kick-out block, but this time with a goal of fighting inside the block with a technique known as the “wrong-arm.” To do this, the defender will attack the offensive player’s inside shoulder, ripping his outside arm across his face.

If done properly, this will force the running back to bounce to the outside, where the force player or players (often times an unblocked Safety or Corner) are waiting to make the play. The spill philosophy, if executed well, is very effective against the power concept as it is predicated on taking the inside running lane away and forcing the ball carrier to find a different running lane to the outside where the force players are waiting.

The videos above do a nice job of showing how to defend the power game by spilling the ball carrier to the outside.

Final Thoughts

While each philosophy is likely to be used at different times in the game and depends heavily on the called defense. In my experience, 3-4 teams often employ the contain philosophy because of the amount of blitzing and man coverage that is used.

Conversely, many 4-3 teams employ a spill philosophy and rely more on zone coverages that help to facilitate the force players necessary for the philosophy to work. These force players are necessary, because the cardinal rule of spilling is being sure you have someone to spill to.

Keep in mind that both philosophies can be successful in stopping the power concept, I just wanted to demonstrate the basics behind them, and demonstrate why the spill philosophy might be something for Oregon to consider in 2014.

It is likely that Oregon utilizes both philosophies in their defensive scheme depending on the call. However, in many of the 3rd down situations versus Stanford, they tried to contain the play and weren’t successful.

On a related note, this post complements the arguments presented by Coach Peterson on the merits of the 4-3 Defense. Please feel free to leave your thoughts in the comments below.

Coach Levi Steier

Albany, New York

(Top photo by Craig Strobeck)

Levi Steier, (Football Analyst) after a collegiate playing career cut short by injuries, began his coaching career as a student assistant at Dakota State University. Since then he has coached primarily at the high school level. During this time he has been a head coach and has coordinated all three phases of the game. He is currently the owner of a web design business and the publisher at OptionFootball.net where he discusses many aspects of football, but regularly focuses on option oriented football topics. Coach Steier enjoys talking football and encourages anyone who would like to discuss the game or find more information to visit his site. You can follow Levi on twitter @OptionFootball, on his Facebook page and on Google+.