The spring season has come and gone in the college football world, it was a teaser sticking around just long enough to leave everyone wanting even more in typical George Costanza-style. It’s often hard to project success or failure based on a few spring practices, and in terms of scheme, most spring games are as bare-bones as it gets.

That being said, for football X-and-O junkies – like me – there’s usually more than a few interesting things to take away from spring practice, and we’re going to talk about one of them today.

The second-level read is something that’s been slowly making its way into the mainstream of college football play-books around the country, and one of the biggest reasons is because the ability it gives offenses to play even more games with opponent linebackers. Charles Fischer talked about it in his recent breakdown of the Oregon Spring Game a few days back, and now I want to dive a little deeper into not only the what, but also the why.

The Gridiron and the Boxing Ring

Several months back, when discussing some of the most basic ideas and philosophies behind this offense and the one Chip Kelly runs in Philly, I mentioned that one of the most important things a good offense has to have is not only a great plan, but also a great plan B. In other words, an offense needs answers to how a defense is going to respond to what they see.

Picture two boxers in the ring circling one another. Both keeping their heads down but just barely sparring with one another, trying to find the weak spot in the other guy’s defense. That’s a pretty good analogy for what goes on in the front end of a football game. There is often a lot more strategy (at that time) than meets the eye, in both boxing and in football.

You’re going to take your hits, and you’re going to land some hits, but you’ve got to be able to adapt once your opponent figures out what you’re trying to do.

What’s your Plan B?

It’s not often that you, as a coach, won’t go into a game with a good idea of what the opponent is going to give you. With so many good coaches in college football and everything on film, it’s very hard to do something completely different from one week to another and be really good at it. These days most coaches focus on doing what they do best and spend a lot of time trying to do it as well as possible.

So, if you know what your opponent is going to do, what’s your plan to stop them? Now, once you’ve figured that out, what’s your Plan B? Or, putting it another way, what’s your counterpunch? Your alternative strategy.

You’re going to need more than one plan of attack for the game, because either:

- You were wrong, and your plan isn’t working as brilliantly as you thought it would, or

- You were right, and you had a great idea of how to stop a particular play or slow down a known offense, only now the offense has adjusted to your defense. They’ve either stopped running that play entirely and begun to take advantage of a new-found weak-spot in your defense, or they’ve adjusted the play itself so that it’s a sound answer to whatever you’re doing.

- Cat, meet Mouse.

The bottom line is that you need answers to what the other guy is giving you. If you’re running the same scheme week after week and showing the same group of plays against every opponent you face, there’s a good chance that you’ll be able to anticipate what the next guy is going to throw at you (pun intended).

Bread and Butter

The plan on both sides of the ball starts with the “bread and butter” play of the offense. As a coach is getting ready to play the Oregon Ducks, what’s one of the plays you know you’re going to see over and over again? What does this group hang its hat on?

The inside zone read, of course. I won’t go into the basics of the play, but if you want to know more, you can click on the link to get a great FishDuck video exploring what it’s all about. The nuts and bolts, let’s say.

So, what are some of the most common ways to defend the play? The answer lies in a defensive alignment that was employed many, many times over the course of the Spring Game.

The Chalkboard

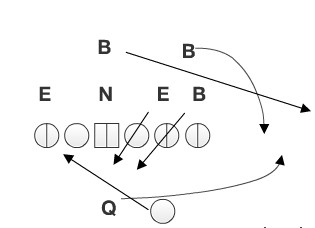

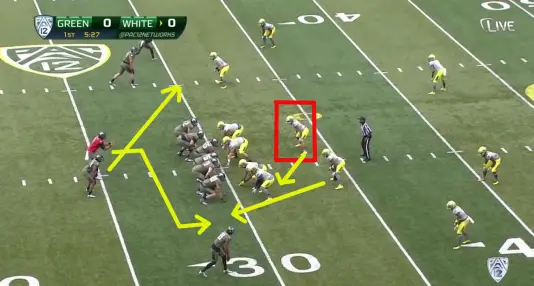

Let’s refer to the diagram. Notice how the linebackers are aligned to the side of the tailback in the backfield. The defense is basically cheating to the side of the back, where most of the time, especially when Oregon runs the inside zone read, the QB will be taking off around the corner to that side.

Defensive coaches spend a lot of time charting where the back lines up in the backfield, in today’s shotgun spread option offenses. There are some defensive coordinators who base their call entirely on where that guy ends up in relation to the QB. Front, back, to the right or to the left.

So, what is the plan once the ball is snapped? The defensive line and backer over the tight end will chase the tailback, and the backers at the second level are responsible for the QB, if he chooses to keep the ball. This would be a typical adjustment by the defense in a situation like first down, when the run is very likely. The defense has the offense figured out — or so they think.

Counterpunch

Necessity is the mother of invention, and obviously this offense needed answers for when defenses started to cheat by playing more aggressively against the zone read. One of those answers is the second-level read that Charles Fischer broke down earlier this week.

The genius of the play lies in a couple of different areas. First of all, the linebackers are cheated so far over to the tight end side, that once they hesitate to play what they think is another typical zone read play, they won’t be able to catch up to the running back sprinting the other way.

In this instance, the QB is reading the linebacker stacked over the nose-tackle, and unless the the backer just completely abandons his responsibility and chases after the tailback right away, this play is going to scream through the defense.

On the other hand, if the linebackers don’t line up the way the offense anticipates, the whole offensive line will be blocking to the right, and should provide an escort for the QB, should he choose to run with the ball.

Conclusion

Like everything else in the Ducks’ offensive arsenal, this version of the second-level read isn’t being run just so the coaching staff can brag about having a bunch of fancy plays in the playbook. The play addresses a specific situation and provides an answer that Oregon faces on a regular basis, and that’s exactly what a good offense is; a well-defined system of plays that compliment one another and provide an offense with answers to different situations, all without getting so intricate that the players can’t execute them properly.

Top photo by Kevin Cline

Related Articles:

Alex Kirby (Writer and Football Analyst) worked several seasons as an assistant football coach at the high school and college levels and is the author of Speed Kills: Breaking Down the Chip Kelly Offense, now available HERE.