It was 1918. After years of unimaginable horror in the trenches of Belgium and France, the Great War ground to a halt. Millions of men and women in uniform — and countless civilians — had perished. The world stood aghast, sighed and buried its fallen.

Back home, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed the 11th day of the 11th month as Armistice Day (now known as Veterans Day). And so it has remained every year since. At the 11th hour on the 11th of November every year, from lavish ceremonies at national cemeteries to small town gatherings at the local Legion, Americans young and old pause for a moment to remember those who paid the ultimate price for the rights and liberties most of us blithely take for granted.

We pause and are reminded as the lonely notes of Taps float across the ocean at Coos Bay or echo off the basalt cliffs of the Gorge, there’s more to life in the end than earning a living, raising a family or… enjoying Ducks football.

Veterans Day has always been a big deal for me. Growing up in Salem, then Eugene, I can vividly recall the shiver than ran up my spine as I sat at the feet of my Grandpa Morse, listening to him dispassionately relate his experiences in World War I.

The falling leaves of an Oregon autumn faded into the background as he told of the German shell that exploded beneath his charging horse, sending him flying, ultimately saved by the deep, soul-sucking mud he’d fallen into when his dead horse landed on top of him.

Grandpa was changed forever by that war. It made him flinty and cynical, impatient and sometimes intolerant. He served with the 42nd Division — the Rainbow Division it was called, because its troops were drawn from across the country, including bright-eyed, eager young men from the hard-scrabble iron ore mining country of northern Minnesota where Grandpa hailed from.

When I was kid I was never able to understand why he was such a hard man. Then, long after he’d gone, I came across James J. Cooke’s The Rainbow Division in the Great War, and in particular this passage from a Lieutenant van Dolsen, that explained it:

Well, we got down into the dug out and, my dear mother, such a shamble I never hope to see again. A long black tunnel lighted just a little by candles, our poor wounded shocked boys there on litters in the dark, eight of them half under ether just as they had come off the tables their legs only half amputated, surgeons trying to finish and check blood in the dark, the floor soaked with blood, the hospital above us a wreck, three patients killed and one blown out of bed with his head off. Believe me I will never forgive the bastards as long as I live.

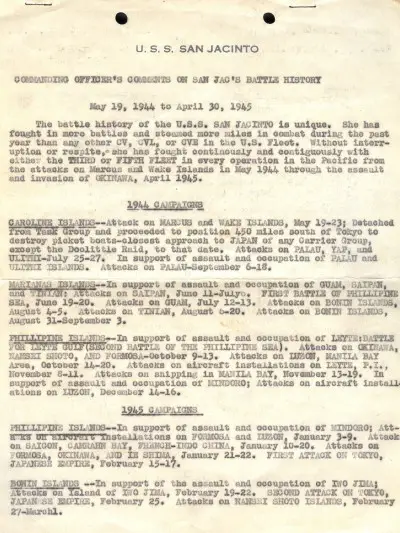

If the First World War changed my grandfather for the worse, World War II changed my dad for the better. Allowed to enlist as an underage recruit, he ended up in the Navy, eventually serving a tumultuous tour of duty in the Pacific on a light attack aircraft carrier, the U.S.S. San Jacinto.

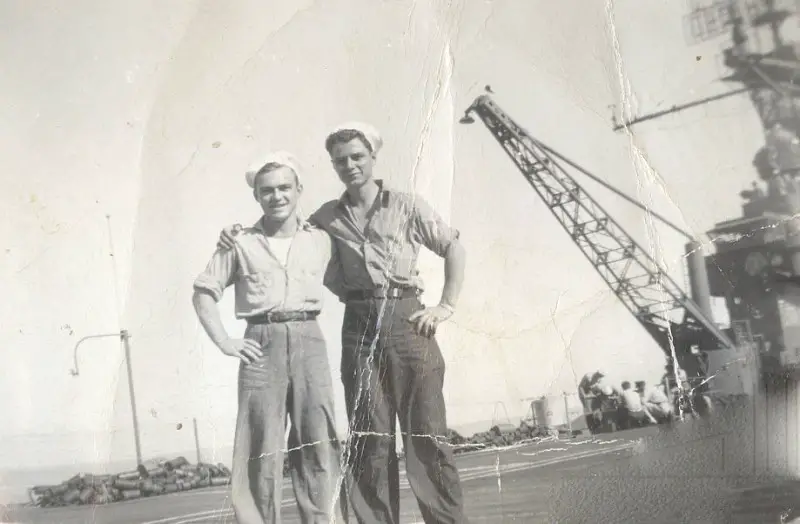

My Dad, Garfield (on the right, now 88 and a rabid Ducks fan) on the deck of the USS San Jacinto, 1944.

From the Battle of Wake Island to the Japanese surrender, the San Jacinto saw continuous action, fighting its way through typhoons with seas that were five storeys tall, and waves of kamikaze suicide attacks. Yes, he experienced both fear and death. But he also forged deep friendships, and perhaps surprisingly, developed a life-long respect and admiration for the Japanese people, thanks largely to the kindness he was met with during his brief tour of occupation after the Japan’s surrender.

Dad’s now 88. He and my marvellous mother are now happy and healthy residents of West Linn. Both are rabid Ducks fans (I doubt there are many men out there who get texts from their 85-year-old mothers during a game, like these from Saturday’s battle in Salt Lake City: “Oh no! A Duck is hurt!” Or “Mariota must be ready for some rest. Wow!”).

Dad’s now 88. He and my marvellous mother are now happy and healthy residents of West Linn. Both are rabid Ducks fans (I doubt there are many men out there who get texts from their 85-year-old mothers during a game, like these from Saturday’s battle in Salt Lake City: “Oh no! A Duck is hurt!” Or “Mariota must be ready for some rest. Wow!”).

Meanwhile my Dad has passed on the sense of loyalty he honed during the War in the Pacific to his grandson — my son, Andreas, now an executive with Edmonton’s North American Soccer League team, FC Edmonton.

I was viscerally reminded of this recently when we all convened in Portland for a niece’s wedding (she’s another Ducks fan, of course). My Dad came away from his years in the Navy with that classic sailor’s souvenir — a tattoo — and Andreas was determined that he and I, to honor Dad’s service and remind the world we’re proud to be Morses, would head to a tattoo parlour in the Rose City while we were all together, and have one just like his grandfather’s done. Adding our first name initials to seal the deal.

So we did. Three generations. A tribute to family, service, and in the end, love.

There’s no game coming up this weekend for the Ducks. No need to scramble to hammer out an article on the upcoming game against Colorado. At least not for me, not today. There’ll be time enough for that, later. No, today I’m going to join a sweet little community choir in the tiny village where I now live, deep in the mountains of southeastern British Columbia.

After the piper and Mountie lead us down to the cenotaph overlooking fjord-like Kootenay Lake. After the bugler’s haunting Last Post wafts out across the waters to be ultimately swallowed by the towering Purcells on the other side of the lake. After we sing a few songs at the local Canadian Legion to a packed house. After all that, I’m going to walk home, start a fire, and raise a glass. To Grandpa. To Dad.

And on behalf of all off us here at FishDuck.com, a glass raised to all those who have served their country and to those who serve her today.

Consider us eternally grateful.

Related Articles:

Chip Kelly Update: Everything's Good Again ...

Chip Kelly Update: Wailing and Gnashing of Teeth

Shock and Awe -- The Oregon Ducks' Football Hangover Effect

Despite Lopsided Score, Georgia State "Never Stopped Believing"

Hope Springs Eternal for Ducks

Incompetent Pac-12 Officials: How Do You Miss ALL of THIS?

Randy Morse (Editor and Writer) is a native Oregonian, a South Eugene High and U of O grad (where he played soccer for the Ducks, waaay back in ’70-‘71). After his doctoral work at the University of Alberta he launched a writing & publishing career – that plus his love of mountaineering has taken him all over the world. An award-winning artist, musician, broadcaster, and author, he’s written 8 books – his writing on media & democracy earned him the Friends of Canadian Broadcasting’s 2014 Dalton Camp Award. He swears he taught LaMarcus Aldridge his patented fade-way jump shot, and is adamant that if he hadn’t left the country (and was a foot taller) he would be the owner of a prosperous chain of fast food outlets and a member of the NBA Hall of Fame by now. If there is a more rabid Ducks fan in the known universe, this would come as a major surprise to Morse’s long-suffering family. He resides in the tiny alpine village of Kaslo, British Columbia.