Florida State defensive coordinator Charles Kelly has quite a task in front of him in the upcoming playoff game. First off, he’s got to prepare for a somewhat unusual offense from Oregon; a high-speed, relentless attack that, oh by the way, happens to be led by Heisman Trophy winner, Marcus Mariota.

It may be the offense that gets most of the credit for the Seminoles’ success, but FSU’s tough defense has kept them in a lot of games that nearly got out of hand, thanks to often shaky play from the last guy to win the Heisman, Jameis Winston. Knowing how important his job is, let’s take a look at some of the tools Kelly has at his disposal to try to stop this offense.

In the last post, we discussed some of the benefits of bringing pressure from the boundary side of the hash, as well as some of the most basic points of strategy and execution. In this article we’re going to do a 180 and take a look at things from the opposite perspective.

Philosophy of the Field Blitz

The idea behind bringing pressure from the field is that the defense will be able to force the offense into playing in a much smaller area than it is used to. By bringing the right amount of pressure and cutting off any attempts to run to the perimeter, the defense hopes that the offense will stick to attacking the boundary area, and thus will end up limiting itself to a more conservative game plan.

The defense loves to see the offense run to the boundary, because there is simply very little space to operate.

It’s also important to note that when discussing the sideline, many defensive coordinators talk about it almost like a 12th defender. On defense, you’ve got to know where your help is, and the sideline is the defense’s biggest ally on the field, because it never misses a tackle. It’s very common to see defenses set an extra man to the field in their pre-snap alignments, so that when so many of the check-with-me style offenses of today start playing the numbers game at the line of scrimmage, they’ll see a numbers advantage to the boundary and not toward the field. In this way, the defense wants to try to limit where the offense can go, and what types of plays it can run. For example, with so little space to the boundary side, it becomes much more difficult to run any kind of perimeter run play, even if an offense may have the numerical advantage at first glance.

Playing the Run and the Pass

One of the biggest problems defensive coordinators face is finding ways to get enough men to the football in the run game, while still keeping enough back in the secondary so that the defense isn’t vulnerable to the long bomb. One of the best ways to get more men to the run game is to get the secondary involved, but then conversely, doesn’t that mean the offense can just start chucking it deep?

To be sure, there is no such thing as a defense that has no holes and no weaknesses. There is no way that eleven men can successfully lock down every inch of the football field, but through good scouting they can severely limit an offense’s choices, and through sound football principles, they can make it as difficult as possible for the offense to gain the upper hand.

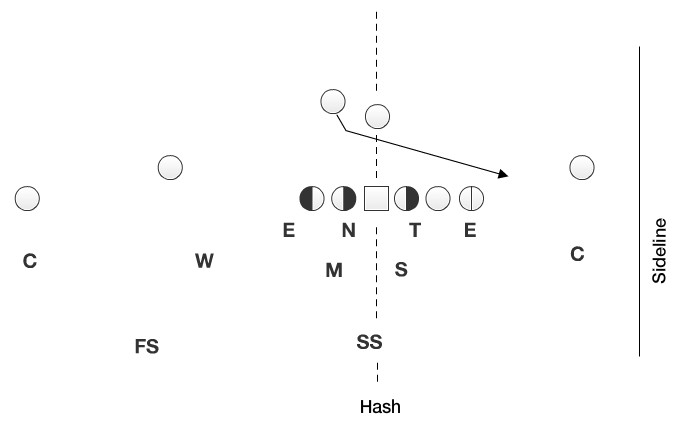

The diagram below is an example of one of the most common ways a defense can get more men to the ball while still keeping the safeties deep to protect against the pass.

Rotating the secondary to the field is one way to get enough men to the ball while still keeping enough defenders to defend against the pass.

As you can see, the secondary has rotated toward the field and the defense has three deep defenders, each responsible for a deep third of the field in pass defense. At the same time, the field-side corner is playing the flat very aggressively, ready to jump on any quick wide receiver screen to that side, and is also responsible for forcing any wide runs back inside to the rest of the defense. This is true with any bubble screens, and in case the offense decides to go with some kind of triple option involving the Z receiver motioning from the other side of the formation, which isn’t out of the question for Oregon.

We can see that each man on the blitz has a particular responsibility when it comes to containing the run game, especially the zone read and the option. This particular coverage does leave some holes to the boundary side of the field, but once again, that’s the idea. The defense wants the offense to settle for attacking the short side of the field, because if you can force a team with as much speed as Oregon to play in a tiny part of the field, you’re able to breathe a whole lot easier as a defensive coach.

The Switch

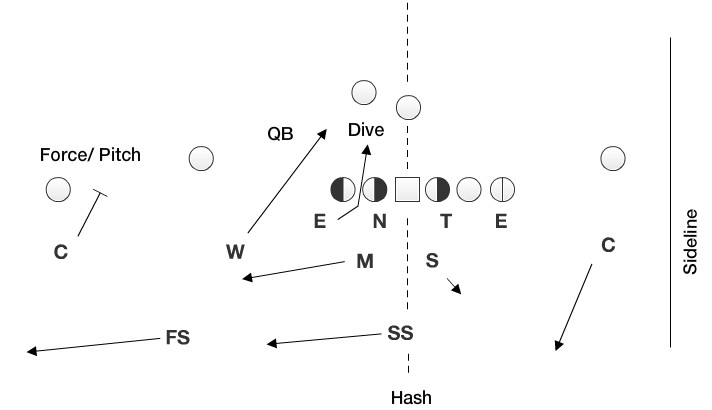

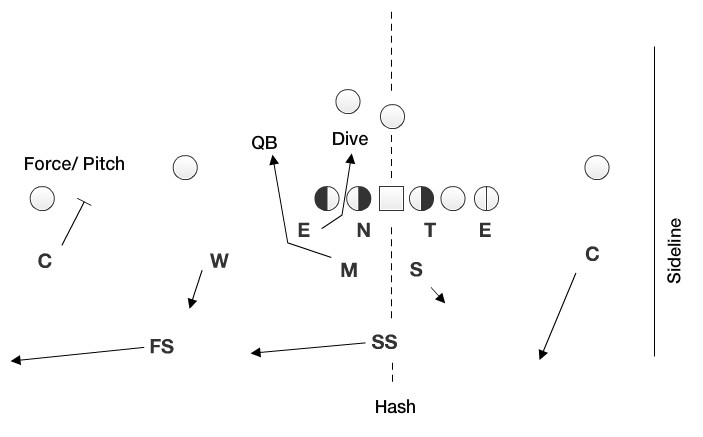

The most challenging part of sending a field pressure against a team that likes to spread the field with its formations is finding a way to replace the man in coverage who was just sent on the blitz. With so much more space to worry about to the wide side of the field, there is obviously a whole lot more space to defend, and more for the offense to exploit.

Sometimes, the guys on the field may get a blitz call, but feel that the alignment of the offense makes it too difficult to play correctly. In this case, the defenders will call a ‘switch’ and exchange blitz and coverage responsibilities. In the diagram below, this time the Will linebacker will cover the short zone over the slot receiver, sometimes called the hook zone, and the Mike backer will take his place on the blitz. These kinds of changes can either be pre-called from the sideline or made on the fly once the defense sees what kind of formation the offense lines up in.

When the offense forces a blitzing defender to align too wide, he has the option to exchange his responsibility with another man on the field.

This not only makes it easier for the defense to stay in a sound alignment so that the defenders are in a better position to do their jobs, but it also prevents prematurely tipping off the offense to what’s coming. It’s the same reason you so rarely see a corner blitz from the wide side of the field. In order to have any chance whatsoever of getting to the QB, he’d have to tighten up his alignment, which would set off an alarm in the QB’s head that something wasn’t right.

Conclusion

Once again, space and numbers are two of the biggest factors when it comes to the X’s and O’s on the field. If it sounds simple, it’s because it is. The offense wants to get the ball in space against as few defenders as possible, and the defense wants to keep the offense from doing so. The only thing left to do is to find creative ways on both sides of the ball to do what they’ve set out to accomplish.

I hope I’ve been able to help you learn a little bit about some of the defensive strategy that goes into game planning for coaches.

Finally, as a member of one of the other 49 states, I believe I speak for every college football fan outside of Tallahassee when I send you and the Ducks the following message:

Featured image courtesy of Craig Strobeck

Related Articles:

Chip Kelly Update: Everything's Good Again ...

Chip Kelly Update: Wailing and Gnashing of Teeth

Shock and Awe -- The Oregon Ducks' Football Hangover Effect

Despite Lopsided Score, Georgia State "Never Stopped Believing"

Hope Springs Eternal for Ducks

Incompetent Pac-12 Officials: How Do You Miss ALL of THIS?

Alex Kirby (Writer and Football Analyst) worked several seasons as an assistant football coach at the high school and college levels and is the author of Speed Kills: Breaking Down the Chip Kelly Offense, now available HERE.