For coaches, watching football broadcasts can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, we all love football, and enjoy watching the best of the best compete against one another. On the other, the guys doing the game on TV often are misinformed about what’s really going on down there on the field when it comes to the X’s and O’s. This may seem like I’m picking on Kirk Herbstreit, but I’m not. I’ve actually done dozens of radio broadcasts for football, and I can tell you that describing what you’re seeing and staying interesting is a lot harder than it looks. He’s actually one of the better in-game analysts for ESPN, but one thing he kept saying over and over during the Rose Bowl was the inspiration for this article.

One thing really annoys me more than it should, and that’s when television analysts refer to all the motions and shifts as ‘window dressing’ in this offense. I suppose the reason I cringe so much when I hear that is because it implies that there isn’t really a whole lot of thought put into it, and that it’s just something thrown in randomly as a change-up. Nothing could be further from the truth, and you’re about to find out why.

In this analysis we’ll go through a couple of examples of when the Oregon offense uses motion, but more importantly, we’ll talk about why the Ducks are doing what they’re doing.

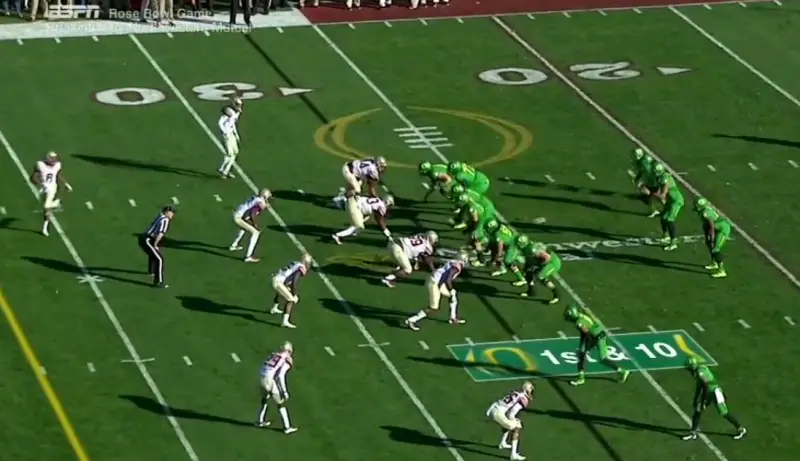

Play #1 – 1st & 10 – 9:00 left in the 1st Quarter

Head Coach Mark Helfrich and Offensive Coordinator Scott Frost dial up a winner right away.

On Oregon’s first play, the offense lines up in the middle of the field in what is a normal 2×2 set. Just before the snap, however, the Z receiver motions back into the backfield, briefly giving the appearance of a two-back set. Mariota finds the TE on the corner route to the deep right for an easy pitch-and-catch for the first down, and the Ducks’ offense gets rolling right away.

So why all the motion? Couldn’t Oregon just line up in that formation to start with and throw the same pass? Well, the short answer is yes. Obviously the Ducks can line up and run pretty much whatever play they want, but keep in mind the situation they’re in at this point.

The motion forces the secondary to adjust, and creates a big window for the TE on the first play of the game.

It’s the first play in the game, so right now, the only thing the Ducks know about Florida State’s defense is what they’ve seen on film. Both teams have had nearly a month to prepare and add new things to the game plan, so while it’s unlikely that they’ll see something completely different from the Seminole defense, it’s very possible that Charles Kelly, the FSU defensive coordinator, has thrown in a few new wrinkles in the practices leading up to this game.

So we’ve established that one reason the offense will put a man in motion is to gain information, another more immediate reason is to force the defense to move with the man in motion, and hopefully show some weak spots. In the next few shots from the game we’ll go through exactly what happens from a defensive perspective that allows the TE to get so wide open.

Oregon aligns in one of their most common formations, then brings the Z receiver in motion toward the backfield.

On the first play, (above) Florida State comes out in a nickel package that is made up of three safeties. This allows the Seminoles to be a little more aggressive against the run, and gives them another man to adjust to the offensive motion that we see in the first picture. What you can’t see from this angle is that the third safety is in the middle of the field. Before the receiver comes in motion, you’ll see a safety near the line of scrimmage, about five yards off, and standing on the hash with outside leverage on the TE. Watch what happens in the next photo.

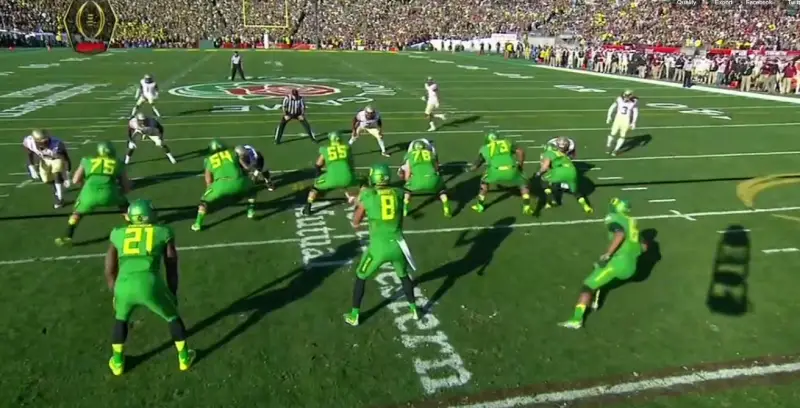

As the Z receiver moves into the backfield, the secondary begins to re-adjust to the new offensive alignment.

As you can see, the safety (No. 8 above) adjusts his position, backing up to a deeper alignment, and now he finds himself inside the TE since the corner has squeezed down and is sitting about where the safety used to be. Now in the next panel, (below) watch how easily the TE gets off the line of scrimmage and finds the green grass.

The TE gets a free release off the line and finds a wide open area in the deep right side of the field.

The defensive end on his outside shoulder barely gives him a shove, and with the corner sitting in the flat on his outside and the near safety to his inside, he gets a free release and makes this an easy throw and catch for the first down.

The alignment of the secondary changes as the offense brings the Z receiver into the backfield.

Before the ball is even snapped, Mariota knows where he’s going with the ball. The secondary’s alignment (above) gives it all away. Even just using the hash mark as a landmark, it’s obvious that the TE is going to be wide open. (The corner, No. 3 is moving inside as is the safety behind him.)

The TE finds nothing but green grass to the deep right thanks to the re-alignment of the secondary.

As the TE runs the corner route and gets behind the CB sitting underneath, he’s in great position to make a play, and he gets the Ducks’ offense going right off the bat.

Motion creates a nice opening for the Tight End.

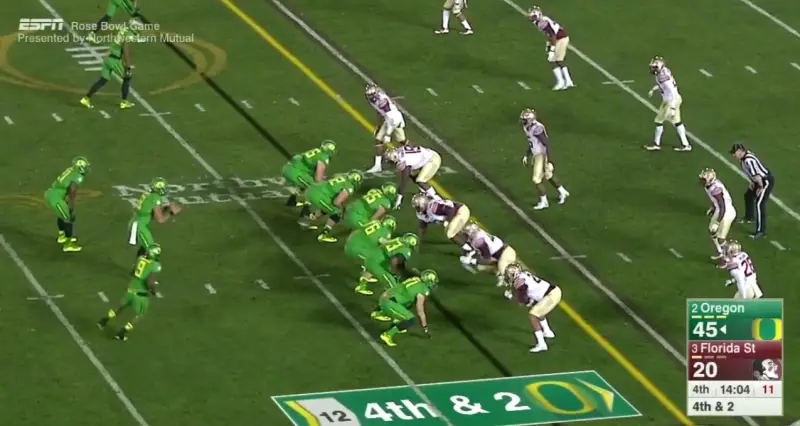

Play #2 – 4th & 2 – 14:06 left in the 4th Quarter

It’s important to realize another reason for offenses to run a particular motion. As we saw in the last example, the Oregon coaches were trying to gauge as much information early on in the game as they could on how the Seminole defense would react to certain formations and motions. By the fourth quarter, they’ve got their answer, and it’s time to go back to the same look they’ve shown a few times in this game. The result is another touchdown that puts the game almost completely out of reach for Florida State.

The motion by the flanker into the backfield provides the offense with good leverage on the edge for a big play.

In this situation, FSU comes out in an odd front with three down linemen, but the reaction (above) to the motion from the secondary is pretty much identical to the first play of the game.

In this example, the offense starts out in a similar formation to the last play we examined.

In the first screenshot, we see the same basic alignment from the corner and the near safety. You can’t see it in this picture above, but there is a cornerback aligned over the receiver who is hidden behind the scoreboard graphic in the bottom right. Note that this is pretty much the same formation that we used for the first example.

Once again the formation goes from a one-back set to a two-back set, and the corner and strong safety adjust their alignments.

The shift in the secondary isn’t as dramatic this time, since it’s 4th and short, so the safeties of Florida State (above) don’t give as much ground as they would a normal down and distance situation. The receiver motions back into the backfield and the near safety and corner squeeze down and get in a little tighter to the formation. The near safety once again comes inside the TE, which will be important once the ball is snapped.

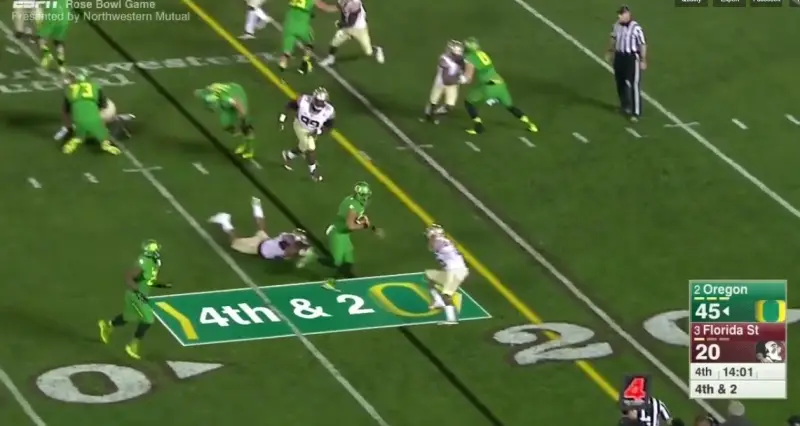

Once the ball is snapped, the TE releases down the field, and Mariota now only has to beat the corner in the flat.

At the snap, we see it’s a Zone Read with the TE (No. 81 Evan Baylis above) going vertical to the first defender at the next level he sees on his inside. It just so happens that this is the near safety. With the linebacker over the outside shoulder of the TE closing down on the dive, Mariota takes the ball with the ability to pitch it to the extra back in the backfield if he needs to.

The strong safety is aligned so far inside after the motion that it makes it easy for the TE to seal him inside. This leaves Mariota one on one to the perimeter.

The near safety is pinned inside by the TE (Evan Baylis above is blocking next to the referee.), whose block was made enormously easier when the safety moved inside of the formation in response to the offensive motion. By the time Mariota gets out on the edge, he’s one-on-one with the cornerback, who is no match for him in the open field. Mariota runs for a score that ices the game, and sends everyone not wearing Florida State colors into a joyful celebration.

Motion brought the safety inside which made an easier block for No 81, Baylis.

Conclusion

After going over these two examples, I hope you’ve been able to see how the Oregon offense uses motion not only to get the looks they want from the defense, but also to use that information to set up big plays later on in the game. At the end of the day, players win ball games, but it’s the coaches’ job to put them in the best possible position to do so, and that’s something that Helfrich and Frost do better than just about anyone in the country.

I may be in Indiana, but “Oh how love to learn about your beloved Ducks!”

Alex Kirby

Oregon Football Analyst for CFF Network/FishDuck.com

Indiana

Featured image courtesy of Craig Strobeck

Alex Kirby is a former high school and college coach who writes regularly at LifeAfterFootballBlog.com and is the creator of DrawFootballPlays.com. He is the author of Speed Kills: Breaking Down the Chip Kelly Offense available on Amazon here.

Alex Kirby (Writer and Football Analyst) worked several seasons as an assistant football coach at the high school and college levels and is the author of Speed Kills: Breaking Down the Chip Kelly Offense, now available HERE.