When a fresh-faced Chip Kelly brought his shiny new version of the spread to the University of Oregon, he probably didn’t know he was about to start a revolution that would take over football from top to bottom. He probably didn’t know he was about to create an archetype that coaches and coordinators would break their blackboards over for the next half a decade. He probably didn’t think he was setting in motion the machine that would chew up the Tampa 2, spit out a Super Bowl champion and then run that over, too. But you know what? Maybe he did.

Kelly’s teams set 29 offensive records at New Hampshire in his final year there alone, during an era that was supposed to be dominated by defense. Ray Lewis and Rod Woodson’s Ravens, Teddy Bruschi and Rodney Harrison’s Patriots, and a vaunted Cover 2 in Jon Gruden’s Tampa Bay were the headliners back then. The great coaches were still thinking down and dirty, still playing old school ball like Kelly’s own high school coach, Bob Leonard, who in Kelly’s own words “averaged 5 passes per game,” and the hottest new look in football was a defensive shell designed to stifle big plays. Hardly the prime incubator for an offensive explosion.

That didn’t stop Chip, and neither did anything the DCs in Durham could do. Seven of the eight teams he coached there averaged over 400 yards per game, and the 2002-2006 teams averaged over 30 points. Coach Kelly was bringing something special, something white-hot, something that couldn’t be contained (no pun intended), and then-Oregon head coach Mike Bellotti, ever an OC at heart, observed, identified and took advantage of it.

Ever since its 1927 advent on Rusty Russell’s Mighty Mites, the spread had been about winning games against better athletes. It was about outmaneuvering your opponent, turning matchups upside down and running circles around a defense that could knock your teeth in if you stood too close. When Chip brought that to a team that already had talent, the stock car turned into a steamroller. 2007 saw Oregon crack #2 in the AP — the Ducks smelled blood, and the rest is history (2007’s injury-driven collapse notwithstanding).

We all remember the glory the speed spread brought to Eugene. Heck, we’re still standing in the middle of it, and we’re not even close to done. What we may not have been as attentive to up here in the foggy forest is what it has done to the rest of the football world.

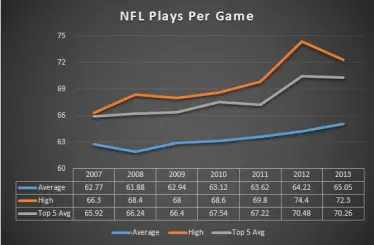

When the Ducks started flashing their new brand of fancy football, the world took notice. New Orleans took a look. Denver took a look. Foxboro took a look. When Chip Kelly took over as OC in 2007, the Saints led the NFL in plays per game with 66.3. When he left in 2012, the Patriots were averaging 74.4. Obviously, the number was slightly inflated by New England’s dominance the regular season that year, but the entire league was trending toward tempo. The NFL average for plays per game rose steadily from ’08 to ’13, and more importantly, the top 5 NFL teams drastically increased their tempo of play calling during that span. The leading edge adapted. The predators pushed their advantage. No huddle plays also rose sharply. Between 2007 and 2012, NFL teams nearly doubled their use of the hurry-up, snapping 2150 times from the no-huddle in the latter year, up from about 1200 in the former.

The Duck offense isn’t all about ticks on the play-clock, though, and neither was its manifestation in the NFL. One of the pillars of the Kelly-built attack in Eugene is its willingness to run when it has numbers at the line. Mariota and Dennis Dixon before him were taught to identify defensive sets with fewer defenders in the box and run straight through them. Tampa 2, that’s you. Two high safeties means if the D is going to cover the whole field, there can only be five in the box. Five run stoppers and five blockers? That’s too easy.

Sorry Gruden, that shell’s toast. Good luck in the analyst’s booth. Oregon forced the NFL to adapt and bring a safety down into the box to respect the run. Thus the Ducks turned the Cover 2 league into a Cover 1 league in which only physical, one high defenses could succeed. Does that description sound familiar? Yeah, that’s Arizona. That’s Seattle. That’s the way defense works now. It’s the way football works now. And it all happened because what happened in Eugene…didn’t stay there.

Top Photo: From Video

Related Articles:

Chip Kelly Update: Everything's Good Again ...

Chip Kelly Update: Wailing and Gnashing of Teeth

Shock and Awe -- The Oregon Ducks' Football Hangover Effect

Despite Lopsided Score, Georgia State "Never Stopped Believing"

Hope Springs Eternal for Ducks

Incompetent Pac-12 Officials: How Do You Miss ALL of THIS?

David Koh (Editor and Writer) is a lifelong sports fan and football nerd. An alumnus of North Carolina State University, where he studied English, and ex-marching band geek, David loves to write as much as he loves learn, and is constantly analyzing the game within the game on the gridiron. He is currently pursuing a career in sports writing, and hopes to one day make a living watching football.