Anyone who has ever laced up or called plays knows that feeling – when a defense aligns itself as if it knows exactly what play is coming. Sometimes, opposing players and coaches even call out the play as if they were in the offensive huddle. And then there are times when everything is aligned just right, and it seems like the defense is out of position. But once the ball is snapped, the defense reacts perfectly and stops the play.

For this reason, teams have installed Run-Pass Option (RPO) plays into their offenses for the QB or sideline to determine whether (and where) to throw or run the ball based on the schematics of the defense.

The following analysis will break down how the Oregon Quick-Strike RPO Scheme is executed, based on pre-snap reads and how the defense reacts once the ball is snapped. In several variations of the RPO, execution ultimately comes down to fundamental option-based football. (Except in this instance, we have swapped a pitch man for a WR screen, and a dive run play for an outside zone play.)

This is a quick-strike RPO. All three phases of this play are executed in 2.2 seconds from the time the ball is snapped until the final option has the ball in his hands.

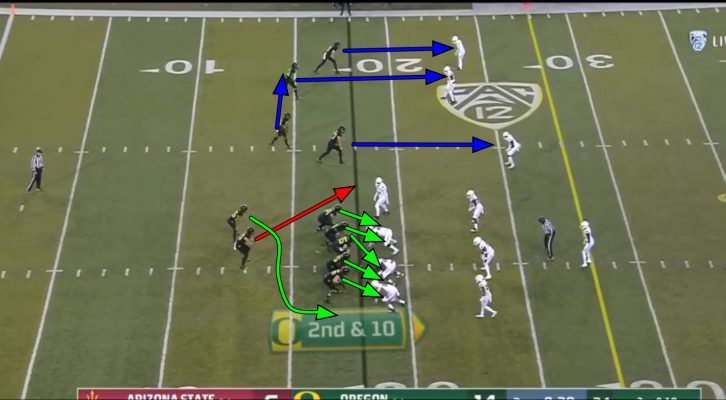

Above, you see how Oregon stretches the defense with both the formation and play design. Each of the three “options” are diagrammed by color to distinguish one from another. The diagrammed schematics of this play allow Oregon to attack both sidelines and the middle of the field.

In the play above, there are three potential outcomes wrapped up in the same “play”: Outside zone, QB keep and WR quick screen. They are labeled in the above picture as follows:

Green – Outside zone (run) Red – QB keep (run) Blue – WR quick screen (pass)

The QB must monitor the box count for the outside zone (green). In this instance, the box count is seven players and a tight safety. The read key for the QB keep is the the first man inside the closest wide receiver (red arrow). And the final read is based on the pass/screen assignments (blue).

The QB Read Progressions

1. Box Count to Play Side

2. The Read Key

3. “When in Doubt, Give Out” to Running Back

The outside zone running play (green above) shows that the defense is keying in on the run with seven players in the box and a tight safety. This tells the QB to cancel the run play since the five offensive lineman are outnumbered. Even though the offense is not blocking the backside defensive end (the read key) they are still outnumbered by one defender and a tight safety.

Most teams would prefer to run the ball, as there are fewer execution hurdles (bad throw, dropped ball, bad route, interception, etc.). A common RPO saying is, “When in doubt, give out!” to the running back. The running back has blockers, and it is a low-risk play to give him the ball. This is why most RPO schemes read the run first with the “Box Count to Play Side” rule. But in this example, the numbers aren’t in the offense’s favor.

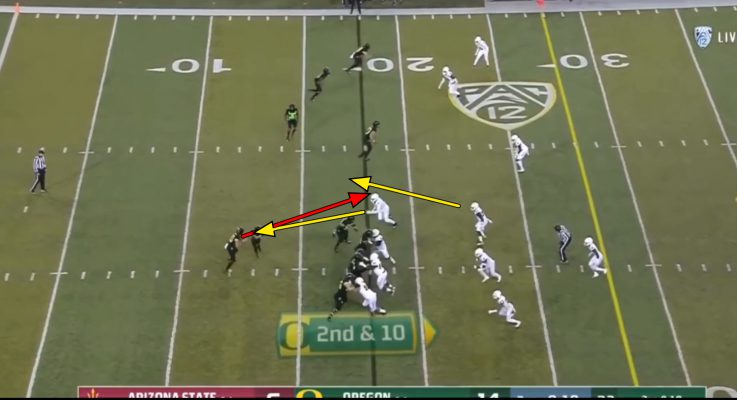

Above is the second progression of the RPO since the outside zone run is shut down. The QB can now focus all of his attention on either keeping the ball or throwing to his left. This is where the QB presents himself as a threat to run the ball and looks to the read key. The read key (red arrow above) now must make a choice between sprinting out into pass coverage or playing the QB run. Once the read key makes his choice, the QB will distribute accordingly. It’s almost like the QB is playing a game of “Keep Away” with the read key.

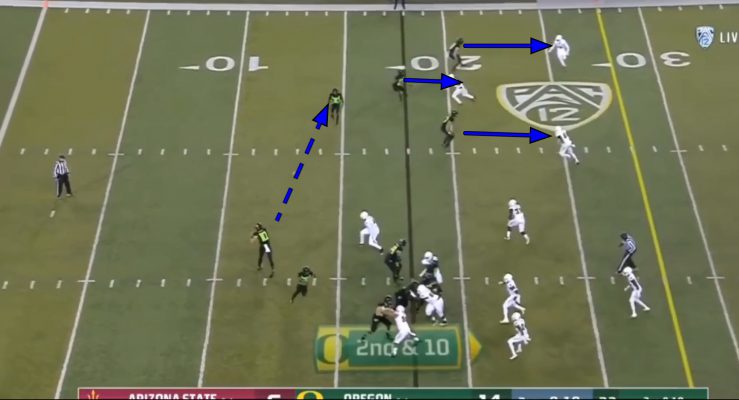

Above, you see the final phase of the RPO. The read key has committed across the line of scrimmage to play the QB run, and the ball is thrown to the quick screen. Oregon has a blocker to account for every defender on the top half of the field. As noted in the beginning of this analysis, the best RPO teams have the ability to get the ball in the hands of their playmakers very quickly. This type of throw, like many RPO throws, does not require the QB to read multiple coverage progressions or fit the ball into a tight window.

The above clip shows the complete play, during which the QB goes through all three reads and elects to pass the ball.

Above is what a similar play looks like when the offense goes with the “run” portion of the RPO. In this play, Arizona State (ASU) has six players in the box, but Oregon only needs to block five of them, with the defensive end being read (and therefore, unblocked). This creates a five-vs-five matchup in the box, which is favorable.

The defensive end is assigned to the QB, so the QB keep is off. The wide receiver screen is not favorable, as ASU has a defensive back pressing the WR, so the screen play is also off. This is an example of an easier read, when a defense aligns to account for the passing threats while leaving the run threat open. It’s also a good example of, “When in doubt, give out!”

The final example above shows how a QB sorts through the reads from the pocket and chooses to keep the ball on a QB run. It is often a process of elimination, so that the QB only has to choose between two plays after the ball is snapped.

So what does this mean for the Ducks moving forward?

The offense had a tendency to start slow last season. But when they incorporated several RPO plays against ASU, they scored 28 points in the first half against a defense that entered the game ranked first in the Pac-12 in tackles for loss and second in sacks. These plays develop quickly (unlike prototypical play action fakes from the pistol) and keep the defense from keying in on one phase of the offense.

Imagine if the Ducks averaged 28 points first-half points from the RPO package against every 2019 opponent as they did against the Sun Devils.

Would Oregon’s slow start scoring issues disappear?

Coach Jeremy Mosier

Geneseo, Illinois Top Photo by Eugene Johnson

Andrew Mueller, the FishDuck.com Volunteer Editor for this article, works in digital marketing in Chicago, Illinois.

Andrew Mueller, the FishDuck.com Volunteer Editor for this article, works in digital marketing in Chicago, Illinois.

Related Articles:

Longtime Oregon Duck fan with family in Portland. Former Offensive coach at Glenwood High School in Illinois. Team qualified for the Sweet 16, 3 Elite 8 appearances, and one state championship game in class 6A. Currently an administrator at Geneseo High School in Illinois. Father to four kids ages 9, 7, 4, and 2 years old. Coached former athletes that have went on to play college football at numerous schools such as Clemson, Duke, and Army. NCAA athlete at Millikin University 2000-2004.