A note from FishDuck.com: Today we have a unique treat, this article from a highly successful coach gives an inside perspective football fans don’t often get to see, the direct insight of football concepts from a coach in the know. This week Coach Curtis Peterson of Glenbard North High School and owner/editor of StrongFootballCoach.com.

We encourage other coaches that are interested in possibly writing guest columns providing their unique insight to please contact us. For now, here is Coach Curtis Peterson!

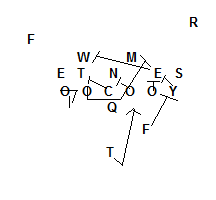

The Power-O, otherwise known as Power, Counter, Counter GT, and “Dave” to Ohio State under Jim Tressel; is a robust blocking scheme designed to overwhelm the point of attack while maintaining a simple yet aggressive way to defeat just about any defensive front. The Power-O is a vital part of my team’s attack, probably 40% of our play calls are a variation of it as either a power or counter. The fundamentals of the Power-O are practiced every day, hammered in through repetition as soon as athletes enter our program so that for both the coaches and players it becomes second-nature.

Some people, however, pigeon hole the Power-O and its blocking scheme relatives as I-formation (or under center) plays, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. The best aspect of the Power-O is that it is robust, simple, and aggressive by nature. It can be adapted to any offense with some small modifications, and perhaps its most flexible use comes from what is generally classified as the “shotgun spread offense.”

Basics of the Power-O

- Holding the edge player accountable (Kickout block, reading him, deceiving him, base blocking him)

- Wrapping/pulling a backside blocker for the play-side inside linebacker (either a guard or fullback)

- Blocking down/getting as many double teams at the point of attack as possible

While most would consider the Power-O implemented mainly in the I-formation, it can be run from a single-back set, a four-receiver set, a two-back set without a tight end, and a two tight end set (with or without two backs). With the spread offense, it can even be run with an empty set utilizing motion.

With all these elements occurring simultaneously, the play can seem confusing to those not used to seeing it. I have a simple method for teaching for the power-o blocking scheme:

- Play-side blocker rules, in order of execution (Tight End, Tackle, Guard, Center)

- Inside gap

- This includes someone blitzing just after the snap

- Play-side combo

- If there is no one in the inside gap, but someone aligned outside (either on you or your play-side teammate), perform a combo block with play-side teammate to the backside linebacker

- Backside linebacker

- If there is no play-side combo available, work immediately to the backside linebacker

- Inside gap

- Backside guard pulls for play-side inside linebacker

- End Man on the Line of Scrimmage (henceforth referred to as EMOLOS) is accounted for by the fullback or QB

- Backside tackle must make sure B gap is protected before working to C gap

Through so much repetition in practice, it gets to the point where we can instruct freshmen in high school just by saying “Inside Gap, Playside Combo, Backside Linebacker.” Usually within a few weeks the freshmen class can block this against most fronts without issue, that’s how simple these rules really are.

Spread Elements to Power-O

Under center variations are very effective at running Power-O for a multitude of reasons, for instance the downhill running (I-formation) or misdirection (wing-T) elements. However the spread can bring a few new elements, while adding or maintaining the others. Better yet it can be flexible, meaning it can give the play new characteristics depending on how it is run.

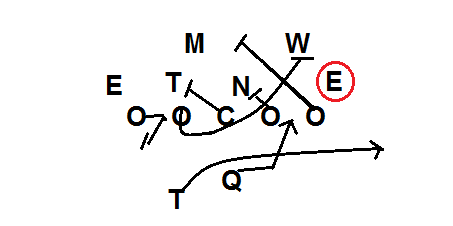

The Option Element

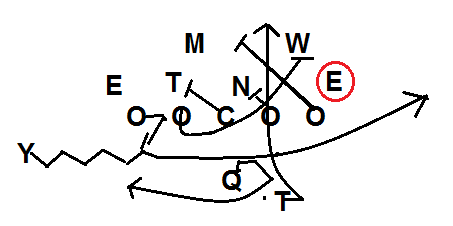

One new element that running the Power-O from the spread gives the play is the ability to read the end man on the line of scrimmage (EMOLOS). Figure 2 shows the traditional way many teams, like Nebraska and Ohio State in 2010, ran Power-O from the shotgun. They read the play-side EMOLOS, with the QB stepping towards the play-side and the tailback taking the ball running horizontally on a sweep path. If the defensive end takes the tailback, the QB dives with the ball, following the guard. If the defensive end crashes on the QB, he gives it to the tailback.

Multiple Ball-carriers

The spread gives the Power-O the chance to have multiple ball-carriers. In figure 2 above, the QB was the main dive player, with the tailback being the stretch player. From a similar look, maybe with the tailback moved back half a yard or so the tailback can then become the dive player. The QB reads the end the same way, “Always give the ball unless I see the EMOLOS’ play-side armpit.”

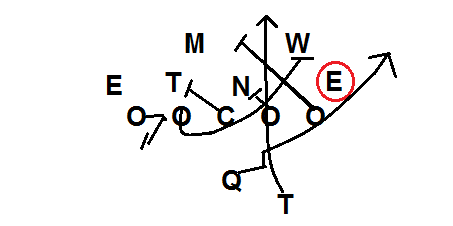

Flexibility and Misdirection Elements

As a coach, one of my favorite things to do is keep the defensive end guessing. It leads to hesitation and second guessing, enabling the offense to have more success at the most important area of the line of scrimmage: the edge of the line.

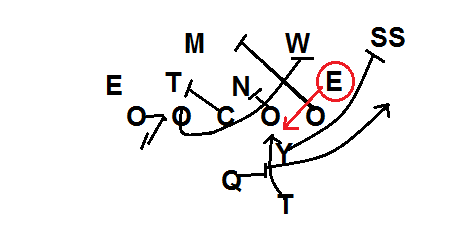

As seen in figure 4, the QB reads the defensive end as before. If he can see the armpit, he gives the ball to player going in jet motion. This can bring the power play directly into an empty shotgun set, again recycling the concept but forcing the defense to think. Most defensive ends aren’t thinking power when the offense is in an empty set, even if the offense is using motion– he’s thinking about sacking the quarterback. By using empty, the defensive end is forced to play honest or get burned.

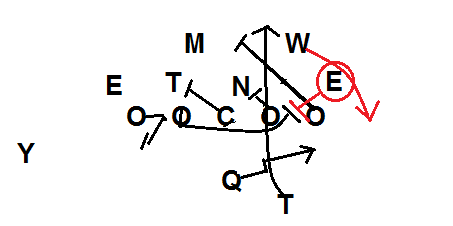

But what if the QB is slow, or coaches don’t want to expose him to a potential injury? Using the one-back shotgun spread, the tailback can take a counter step towards the jet sweep side, and come downhill taking the ball on the power-o. This results in essentially combining figure 3, with the runningback being the dive, and the jet sweep element in figure 4. This gives both flexibility and the ability to deceive the defense.

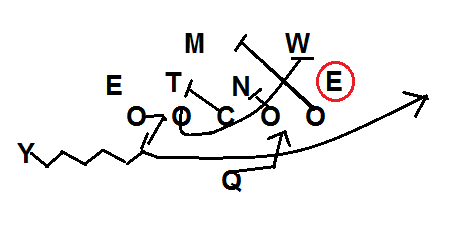

Two Back, Downhill Power-O from the Shotgun

Maybe the most exciting element of Power-O is the downhill running potential. This is a major contributing factor as to why many teams don’t run it from the spread, because they don’t believe the downhill running opportunities exist. Power-O, by definition, is aggressive. Some teams think it must be run downhill, and preferably not with a quarterback. Well, it can still accomplish this from the shotgun (and the pistol too).

The offense can be in the shotgun with two backs (a tight end is not necessary though welcome), and run Power-O reading the EMOLOS. This is especially effective when teams prefer to not use a 3 technique (defensive tackle aligned outside shoulder of the offensive guard) to the runningback, but instead set him to the field or to the slot receiver.

Figure 6 illustrates that every defender in the tackle box can be accounted for, specifically that pesky strong safety (usually the preferred method to defeat run formations, especially if a 3-technique isn’t present to a side), by arc releasing the fullback to him. That fullback’s arc release protects the QB if keeping the ball dictated by the defensive end’s actions. However, the fullback can also block the safety from the inside out if the read results in a dive. Obviously, the reaction of the defense determines the blocking assignment for the fullback.

False Rumors on Stopping Power-O from the Spread

A lot of teams will simply perform a fairly straight-forward gap exchange to stop Power-O, which is why many teams avoid it from a spread look. It became a very good way to stop the power-o, and a big reason Taylor Martinez at Nebraska had less success later in his freshmen year running the ball compared to the early parts of that season. The defensive end will crash, and the outside linebacker will sprint to the outside.

Well, the simplest way to counter this is to simply turn Power-O from the spread into an old school trap play. Adding a simple tag to the play call can tell the guard to kick-out the EMOLOS as he crashes. If the guard is better at run blocking, specifically trapping or kicking out defenders, than the defensive end is at wrong arming or playing the run, then this can work out very well. While the ability to block the play-side linebacker is lost, if they are performing the gap exchange as mentioned, the outside linebacker should already be out of the picture because he scraped to the outside as part of his rules for the gap exchange.

The play is essentially an automatic give, and the tailback will stay inside the guard’s kickout. Northern Illinois did this to perfection last year in their vaunted ground attack. In the video below, you’ll see Northern Illinois’ QB Chandler Harnish, in the second or third play, actually keep the ball underneath a trap block similar to the above figure.

Conclusions on the Power-O from the Spread

This overview skipped over the basic other requirements of the Power-O to discuss its flexibility. While the play is simple to install, it is by no means basic. Especially in the spread offense, timing in the development of the play is very critical. Working on the timing with the offensive linemen is a huge point of emphasis. Building a football practice plan designed to develop the skills necessary to run the play is essential. If the offense is using both pro style under center looks and spread sets, a team can easily use both variations without teaching many new skills, and just focus on getting the timing down.

Please note, this play can be run to a 3-technique side as well, even though this isn’t illustrated in the figures above (this means the defensive tackle is over the play-side guard and the nose tackle is in the backside A gap). Some teams prefer to run power or counter to a specific side (see the red or white theory of play-calling), but I believe it’s effective either way.

Overall, the Power-O is a way for teams to overwhelm defenses at the point of attack. With defenses becoming more aggressive and showing multiple fronts against the spread, the Power-O offers a simple yet effective way of combating them with the running game.

If you want more information on the Power-O, check out my football coaching blog, Strong Football. If you are looking for offensive line drills or running back drills to help make the play work, check them out at Strong Football. I welcome and look forward to any questions you may have!

Related Articles:

Curtis Peterson started coaching football in 2005 and he is the founder of Strong Football. He is currently a football coaching consultant for a few teams in the midwest. Coach Peterson welcomes your feedback, please follow him on Twitter at @CoachCP.