commons.wikimedia

The ankle ligamentous sprain injury is the most common single type of acute sport trauma. Over the years, various preventive strategies have been implemented. However, a recent epidemiology revealed that ankle sprain injuries still dominated in sport injury, as it accounted for 14% of all attendance in an accident and emergency department. In the recent decade, the growing orthopaedic biomechanics techniques have enhanced a better understanding of the injury mechanism, and the subsequent research in sports injury prevention and management.

Sports participation and sports injury:

All around the world, medical doctors and sports scientists were actively promoting regular physical exercises to gain health benefits and to prevent cardiovascular-related disease. People nowadays are more eager to participate in sports and exercises for personal interest, leisure, relaxation, health and fitness purposes.

In Hong Kong, according to the annual survey of sports participation conducted by the Hong Kong Sports Institute, people in general were becoming more active in sports participation from 1996 to 2001. The increasing trend was found in youngsters and the elderly, as well as in the working population. The increasing sports participation was also reflected by the number of participants in the annual marathon race. There were only 1,000 participants in the first marathon race in 1997. The number of participants increased every year, and reached 10,000 in 2001. The number of participants kept increasing in recent years and has dramatically increased to 50,000 in 2008. Most of the participants were recreational athletes, indicating a mass participation of sports among the population.

However, contrary to the promotion of the health benefits from sports participation, sports often cause injuries. A study in Sweden reported that 17% of the 3,341 acute visits to a clinic due to accidents in a one-year prospective study, were from sports. It was comparable to home accidents (26%), work accidents (19%) and was much higher than traffic accidents. In the United Kingdom, 7.1% of 2,432 new patients attending accident and emergency departments in a 10-day period, sustained trauma from sports. In Northern Ireland, in adolescents age 11-18 who actively participated in sports, as many as 51% of these participants sustained sports injuries. When the sports participation rate became high, the exposure to potential injury increased – thus the high incidence of sport injury.

Ankle anatomy and biomechanics:

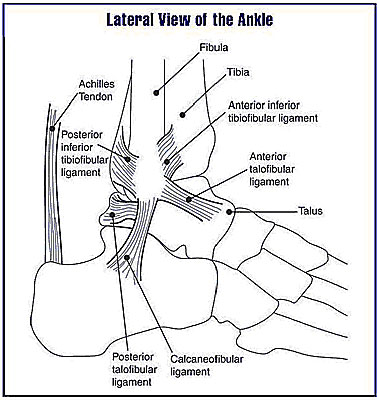

In human anatomy, the ankle joint is where the foot and the leg segments meet. It is comprised of three major articulations: the talocrural joint, the subtalar joint and the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis. The talocrural joint is also termed the tibiotalar joint or the mortise joint, and is formed by the articulation of the dome of talus, the tibial plafond, the medial malleolus and the lateral malleolus. This joint, in isolation, behaves rather like a hinge joint that allows mainly plantarflexion and dorsiflexion. The fibula extends further to the lateral malleous than the tibia does, to the medial malleolus, thus creating a block to eversion (a turning outward or inside out, such as a turning of the foot outward at the ankle). Such a body feature mainly allows for a larger range of inversion (tilting of the sole inwards) than eversion, thus, inversion sprains are more common than eversion ones.

The talocrural joint is supported by several main ligaments, namely the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) and the posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL) at the lateral aspect, and the deltoid ligament in the medial aspect of the ankle. Among the lateral ligaments, the ATFL is the weakest as it has the lowest ultimate load, approximately 138.9N, which is about half of that of PTFL, that is, 261.2N, and one-third of that of CFL, that is, 345.7N. These values were obtained from mechanical tests on ligaments of fresh human ankles. The ATFL is approximately 20-25 mm long, 7-10 mm wide and 2 mm thick. It originates from the anterior-inferior border of the fibular and inserts to the neck of the talus. It prevents anterior displacement and internal rotation of the talus, especially when the talocrural joint is plantarflexed. Due to its low ultimate load and the anatomical positions of origins and insertions, the ATFL is most commonly injured in a lateral ankle sprain.

|

HISTORY OF INJURY |

| Plantarflexion and inversion stresses injure anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL); with progressive force injuring calcaneofibular, posterotalofibular, and tibiofibular ligaments in severe strains. |

| Inversion stress in neutral position injures calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) |

| Dorsiflexion stresses tibiofibular ligaments (higher ankle) |

| Eversion and external rotation injuries, deltoid ligament medially and tibiofibular ligament laterally, often accompanied by fibular fracture. |

Table 1. Injury History. © 2013, Dr. Jacob L. Driesen

Lateral Ankle Sprain

Lateral ankle sprains are common acute injuries suffered by athletes. The most common mechanism for a lateral ankle sprain is excessive inversion and plantar flexion of the reafoot (not a misspelling) on the tibia (the inner of the two bones of the leg that extend from the knee to the ankle and articulate with the femur and the talus; shinbone). The injured ligaments are located on the lateral aspect of the ankle and include the anterior talofibular, the posterior talofibular and the calcaneofibular.

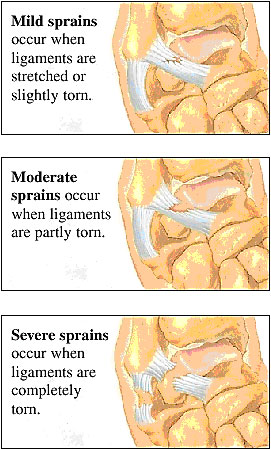

With lateral ankle sprains, the severity of the ligament damage will determine the classification and course of treatment. In a Grade 1 sprain, there is stretching of the ligaments with little or no joint instability. Pain and swelling for a Grade 1 sprain are often mild and seldom debilitating. After initial management for pain and swelling of the Grade 1 sprain, rehabilitation can often be started immediately. Time loss from physical activity for a Grade 1 sprain is typically less than one week.

Grade 2 sprains occur with some tearing of ligamentous fibers and moderate instability of the joint. Pain and swelling are moderate to severe and often, immobilization is required for several days.

With a Grade 3 sprain, there is total rupture of the ligament with gross instability of the joint. Pain and swelling is so debilitating that weight bearing is impossible for up to several weeks.

Rehabilitation Expectations

With lateral ankle sprains, regaining full range of motion, strength and neuromuscular coordination, are paramount during rehabilitation. Isometrics and open-chain range of motion can be completed by those patients who are non-weight bearing. Range of motion should focus on dorsiflexion and plantar flexion and be performed passively and actively, as tolerated. During early rehabilitation, towel stretches, and wobble board range of motion should be introduced, as tolerated. Stationary biking can aid dorsiflexion and plantar flexion motion in a controlled environment while also providing a cardiovascular workout for the athlete. Clinicians can also incorporate joint mobilizations to aid in dorsiflexion range of motion. Hydrotherapy is an excellent means to work on range of motion, while also gaining the benefits of hydrostatic pressure.

Once weight bearing is tolerated, middle-stage rehabilitation is started. This includes balance and neuromuscular control exercises, as well as continued range of motion exercises, as tolerated. Balance activities should progress from double-limbed stance to single-limb stance, as well as from a firm surface to progressively more unstable surfaces. Closing the eyes or incorporating perturbations, can further challenge patients. Patients can be asked to throw and catch weighted balls, perform single-leg squats, and perform single-limb balance and reaching exercises. Regaining and maintaining range of motion should be continued. Wobble board training and slant board stretches are also important to focus on heel cord stretching.

|

|

Summary of the Treatment Methods for Ankle Sprain Injury |

|

|

|

Treatment |

Effect |

Detail |

|

| Aircast ankle brace | Significant improvement in ankle joint function at both 10 days and one month compared with standard management with an elastic support bandage. | Application of a semi-rigid ankle brace consists of two contoured thermoplastic lateral straps lined with foam pads and designed to fit against the medial and lateral malleoli of the ankle joint. The aircells can be supplemented with additional air through an inlet port. The rigid sidewalls are held in place with Velcro strapping. | |

| Elastic support bandage | Improve single-leg-stance balance and might decrease the likelihood of future sprains. | ||

| Training on wobble board | Anteroposterior and mediolateral stability improved after training. | Patient practices balancing on a rectangular or square platform with a single plane-rounded fulcrum underneath that extends the width of the board. | |

| Ankle disk training | Balanced improved after training. | Patients have to balance the circular platform with hemispherical ball underneath, without allowing the edges of the platform to touch the floor. | |

| Imagery | Greater muscle endurance than the control group. | Movement imagery, including visual imagery of movement itself and imagery of kinaesthetic sensations. | |

| Resistive walking boot | Patients’ ankle were immobilized by walking boot with aircast support and compression wrap in the first 0-5 days after injury. | ||

| Traditional Chinese medicine methods | Drug treatment, electroacupuncture, massages. | ||

Table 2. Summary of the Treatment Methods for Ankle Sprain Injury, © 2013, Dr. Jacob L. Driesen

Other Ankle Sprains

Although less common, medial and syndesmotic ankle sprains: The common mechanism of injury is sport and most often they occur during forceful twisting outward of the ankle. This injury is more common in football, hockey, wrestling and soccer. In these sports the opportunity to become tangled under another person is increased. The outward twisting motion of the ankle will cause the two bones to pull away from one another and tear the ligaments that connect them.

Another way to injure these ligaments is via hyperdorsiflexion — which means that the toes are forced toward the shin beyond their normal range (also known as a ‘high-ankle sprain’). This will occur when an athlete has his foot planted and falls or is pushed forward. In either event the splaying (pulling apart) of the two bones causes the ligaments to tear, often resulting in more severe injuries and causing a longer time to heal and rehabilitate. Medial ankle sprains occur with a mechanism of excessive eversion and dorsiflexion, causing the deltoid ligament to be injured. Patients with medial ankle sprains will often be present with swelling and discoloration on the medial aspect of the ankle and unwillingness to bear weight.

Syndesmotic Sprains (stability of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis is necessary for proper functioning of the ankle and lower extremity).

Much of the ankle’s stability is provided by the mortise formed around the talus (the large bone in the ankle that articulates with the tibia of the leg, and the calcaneum and navicular bone of the foot by the tibia and fibula). The anterior and posterior inferior tibiofibular ligaments, the interosseous ligament, and the interosseous membrane act to statically stabilize the joint. During dorsiflexion, the wider portion anteriorly more completely fills the mortise, and contact between the articular surfaces is maximal. The distal structures of the lower leg primarily prevent lateral displacement of the fibula and talus and maintain a stable mortise.

A variety of mechanisms individually or combined can cause syndesmosis injury. The most common mechanisms, individually and particularly in combination, are external rotation and hyperdorsiflexion (severe backward flexion or bending, as of the hand or foot). Both cause a widening of the mortise, resulting in disruption of syndesmosis and talar instability that occur with disruption of the interosseous (or syndesmotic) ligament that stabilizes the inferior tibiofibular joint. Injury to this ligament occurs with excessive external rotational or forced dorsiflexion.

Syndesmotic sprains may occur in isolation or in combination with medial or lateral ankle sprains. Due to limited blood supply and the difficulty in allowing the injured ligament to heal unless the ankle is immobilized, injuries to the syndesmotic ligaments often take months to heal. Patients with syndesmotic sprains are often present with a lack of swelling, but will be extremely tender over anterior aspect of the distal tibiofibular joint.

Rehabilitation Expectations

Initial treatment for both medial and syndesmotic sprains is often immobilization and crutches. During this time, swelling and pain management are the primary concerns. The length of time of immobilization will vary among patients and will depend on the severity of the sprain. While immobilized, patients can work on controlled open-chain range of motion, focusing on dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. During this time, inversion and eversion should be held to a minimum. During early rehabilitation, nothing should increase pain or swelling to the area.

Once weight-bearing is tolerated, crutches should be used at a minimum. Gait training may be needed to ensure the patient is not compensating in any way, which may cause secondary injury. At this point, rehabilitation will follow the progression, as stated above, in the lateral ankle section. Rehabilitation concerns include: pain and swelling, range of motion, strength, balance and neuromuscular control, and functional exercises.

Criteria for Full Competition

Full return to activity should be a gradual progression in order to stress the ligaments without causing further harm. Full activity should be allowed once the athlete has complete range of motion – 80 to 90 percent of preinjury strength – and the ability to perform gait activities (including running and changing direction) without difficulty. The athlete should be capable, without pain or swelling, to complete a full practice.

Patient Education

With medial and syndesmotic sprains, patience is the most important thing for the patient to learn. The healing of the medial and syndesmotic ligaments take time, sometimes up to several months to fully heal. The difference in the expectations of these injuries compared to lateral ankle sprains must be emphasized to all stakeholders, so that realistic expectations for return to play can be understood.

Plantar Fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis is the catchall term that is commonly used to describe pain on the plantar aspect of the proximal arch and heel. The plantar fascia is an aponeurosis (a sheetlike tendinous expansion, mainly serving to connect a muscle with the parts it moves) that runs the length of the sole of the foot and is a broad, dense band of connective tissue. It is attached proximally to the medial surface of the calcaneus and fans out distally, attaching to the metatarsophalangeal articulations and merges into the capsular ligaments. The plantar aponeurosis assists in maintaining the stability of the foot and secures or braces the longitudinal arch.

Plantar fasciitis is caused by a straining of the fascia near its origin. The plantar fascia is under tension with toe extension and depression of the longitudinal arch. During normal standing (weight bearing principally on the heel), the fascia is under minimal stress, however, when the weight is shifted to the balls of the feet (running), the fascia is put under stress and strain. Often plantar fasciitis is a result of chronic running with poor technique, poor footwear, or because of lordosis, a condition in which the increased forward tilt of the pelvis produces an unfavorable angle of foot-strike when there is considerable force exerted on the ball of the foot.

Patients more prone to plantar fasciitis include: those with a pes cavus foot (high arch); excessive pronation; overweight; walking, running, or standing for long periods of time, especially on hard surfaces; old, worn shoes (insufficient arch support); and tight Achilles tendon. The patient will present with pain in the anterior medial heel, usually at the attachment of the plantar fascia to the calcaneus. The pain is particularly noticeable during the first couple of steps in the morning or after sitting for a long time. Often the pain will lessen as the patient moves more, however the pain will increase if the athlete is on his/her feet excessively or on his/her toes often. Upon inspection, the plantar fascia may or may not be swollen with crepitus. The patient’s pain will increase with forefoot and toe dorsiflexion.

Rehabilitation Expectations

Depending on patient compliance, plantar fasciitis can be a very treatable minor injury with symptoms lasting days. However, without proper treatment and patient compliance, plantar fasciitis can linger for months or even years.

Initial treatment of plantar fasciitis starts with pain control. Rest is extremely important at this time, patients should not be performing any unnecessary weight-bearing activities. Patients should also be wearing comfortable supportive shoes when walking is necessary. Adding a heel cup or custom foot orthosis to a patient’s shoe, may relieve some of the pain at the plantar fascia insertion. During this time, regaining full dorsiflexion range of motion of the foot, as well as of the big toe, is vital. Towel stretches, slant board stretches, and joint mobilizations administered by a rehabilitation clinician will aid in the return of dorsiflexion range of motion.

After pain is reduced, strengthening exercises can be incorporated into rehabilitation. The focus should be in strengthening some of the smaller extrinsic and intrinsic muscles of the foot. Towel crutches, big toe-little toes raises, short foot exercises are good examples of strengthening exercises (Fig 3). Throughout the treatment and rehabilitation process, soft tissue work, such as cross-friction massage, may aid in the alleviation of symptoms.

Short foot exercises are performed by contracting the plantar intrinsic muscles in an effort to pull the metatarsal heads towards the calcaneus. Emphasis should be placed on minimizing extrinsic muscle activity.

Criteria for Full Competition

Although athletes can often continue to participate fully while suffering from plantar fasciitis, it should be understood that the longer activity is continued, the longer the symptoms will linger. For best recovery of this injury, extra activity should not be started until the athlete is able to walk a full day without any pain. Once daily activities are tolerated, activity can be slowly increased until full participation. Throughout the rehabilitation and participation progression, stretching should occur often throughout the day.

Clinical Pearls

- While sitting, roll on a ball (tennis ball, golf ball, etc) underneath the medial longitudinal to stretch the plantar fascia.

- Fill a paper cup with water and freeze it, roll on the frozen cup to get the benefits of cold, while also stretching the plantar fascia.

- Before getting out of bed in the morning, put on shoes with good arch supports, to provide the plantar fascia support upon weight-bearing.

- Sleep with feet off the end of the bed to allow some dorsiflexion while sleeping.

- Wear a night splint that will keep the foot in a dorsiflexed or neutral position.

- Stretching often throughout the day, for a short period of time, is more beneficial then stretching once a day for a long period of time.

- Do not wear high-heels or other shoes with no support (sandals), during the day.

Patient Education

Plantar fascia tends to be a cyclical injury. Athletes will repetitively suffer from this injury because, after the initial injury, the cause of the injury is not treated, only the symptoms. Patients with plantar fasciitis need to have their gait biomechanics thoroughly evaluated and, if necessary, be fitted for custom orthotics.

Achilles Tendonitis

Achilles tendonitis is an inflammatory condition that involves the Achilles tendon and/or its tendon sheath. Achilles tendonitis is the most common “overuse injuries” reported in distance runners. Although Achilles tendonitis is generally a chronic condition, acute injury may also occur. Typically, the athlete will suffer from gradual pain and stiffness about the Achilles tendon region, 2 to 6 cm proximal (nearest; the opposite of proximal is distal) to the calcaneal insertion. The pain will increase after running hills, stairs, or an increased amount of sprints (running on toes). Upon evaluation, the gastrocnemius and soleus muscle testing may be normal, however flexibility will be reduced. Having the patient perform toe raises to fatigue will show a deficit compared to the uninvolved limb. Inspection of the area may feel warm to the touch and pain, tenderness and crepitus may be felt with palpation. The tendon may appear thickened indicating a chronic condition.

Rehabilitation Expectations

Healing of Achilles tendonitis is a slow process due to the lack of vascularity (blood vessels); thus, low blood supply to the tendon. Initially, patients will feel comfortable by placing less stress to the area by wearing a heel cup. Resting and activity modification is important during the initial healing stages. The clinician needs to emphasize the importance of allowing the tendon to heal. During this time, cross-friction massage can be started to the area, to break down adhesions and promote blood flow to the area.

Stretching and strengthening of the gastrocnemius-soleus complex (the most superficial of the muscles of the back of the lower leg. It arises from the medial and lateral femoral condyles by two heads which join to form the inferior border of the popliteal fossa behind the knee). Together with its smaller accessory, the plantaris, and the soleus muscle (arising from the shaft of the tibia), converges onto the Achilles tendon, to be inserted into the middle of the back of the calcaneum. It acts to plantarflex the foot and raise the heel when walking. Gastrocnemius and plantaris, which also act as weak flexors at the knee, should be incorporated.

Towel stretching and slant-board stretching should be done throughout the day, as tolerated by the patient. As range of motion is restored, the heel cup should be removed to reduce the chances of adaptive shortening of the muscles and tendon. Progressive strengthening including toe raises and resistive tubing, should be incorporated at the beginning of rehabilitation. Sets should start low with low reps and gradually increase to low sets high reps for endurance, as tolerated by the athlete. As pain and inflammation decreases, machine weights, lunges, and sport-specific exercises can be added. Eccentric exercises for the triceps surae often have beneficial results in athletes with Achilles tendonitis.

The patient’s foot structure and gait mechanics should be evaluated for possible orthotic benefits. Often Achilles tendonitis is a result of hyperpronation, an abnormality that can be addressed with foot orthotics. Once range of motion, strength and endurance has returned, athletes should slowly progress into a walking and jogging program. Workouts should be done on a flat surface when possible. The walking and jogging program should start out with slow mini-bursts of speed. The program is to increase the amount of stress the Achilles tendon can tolerate; it is not to improve overall endurance. As tolerated by the patient, running and sprinting can be increased.

Criteria for Full Competition

Athletes should be allowed to compete when full range of motion and strength has returned. The athlete should have regained endurance in the involved limb and be capable of completing a full practice without pain. Depending on the sport, some athletes may be able to compete, while suffering from Achilles tendonitis. However, patients should be educated in the fact that the condition will not go away without proper rest and treatment.

Patient Education

Patients need to be educated with the risks of Achilles tendonitis, specifically hill running, lack of proper shoes, lack of rest, and flexibility. Hill workouts increase the stress and strain to the gastrocnemius-soleus complex and Achilles tendon. Hill workouts should be done at a maximum once a week, to allow the body time to heal. Similar to any chronic injury to the feet, shoes must be evaluated. Athletes need to learn and understand their foot type and the proper shoes for their foot type. Also, shoes should be replaced every 500 miles or a maximum 2 years. Running on old worn shoes will alter biomechanics and cause stress and strain to the body. Finally, the lack of flexibility is often the main culprit in Achilles tendonitis. The importance of stretching — and stretching often – should be emphasized.

Prophylactic Support

Initially, heel cups will reduce the tension and stress placed on the Achilles tendon. As flexibility is regained, the heel cup should be gradually reduced, to minimize the chances of an adaptive shortening of the tendon. Athletes may find comfort in a special tape job that will reduce the stress placed on the Achilles tendon, as well. The patient’s foot type and gait mechanics should be evaluated for possible use of custom orthotics. Achilles tendonitis can often be attributed to over pronation during gait. A custom orthotic will be able to adjust the athlete’s gait, to reduce this abnormality.

Turf Toe

Tuft toe is a hyperextension injury of the great toe, causing a sprain to the metatarsophalangeal joint and damage to the joint capsule. Turf toe can be either an acute or a chronic condition. An acute turf toe often occurs when the athlete’s shoe sticks into the ground, while he/she is trying to stop quickly. The shoe sticks as the individual’s body weight shifts forward, causing the big toe to jam into the shoe and ground. The chronic condition occurs from frequent running or jumping in shoes that allow excessive great toe motion. This mechanism of injury may occur on natural or synthetic surfaces.

Athletes with turf toe will be present with pain at the 1st metatarsophalangeal joint. Swelling and stiffness may be present, however pain, especially with great toe extension, is the primary symptom. Rehabilitation of turf toe typically requires several weeks. If left untreated, turf toe can lead to permanent decrease in range of motion and osteoarthritis.

Rehabilitation Concerns

Patients suffering from turf toe respond best with rest and an adjustment made to their shoes. Pain management should be of primary concern to the clinician. Once pain and swelling have been reduced, the athlete should start performing toe extension and flexion exercises, such as toe crunches and short foot exercises. Joint mobilizations should be added to the treatment protocol, to aid in pain and increase range of motion. Once pain and swelling is reduced, the athlete may begin to progress into athletic activities. Protecting the great toe with a stiff forefoot insert or a great toe taping, may increase athlete comfort.

Criteria for Full Competition

Athletes are able to return to full competition when any pain and swelling has resolved. Often athletes with turf toe are capable of continue their practicing and participating, while suffering from this injury with the toe being taped and possible inserts into shoes.

Pearls of Wisdom

- Have patients wear stiff-insole shoes to prevent excessive motion.

- Great toe joint immobilizations can be incorporated to reduce pain and increase motion.

Patient Education

Patients should be aware that if left untreated, turf toe may cause permanent decreased range of motion in the great toe and bone spurs may develop. Although athletes can often play with turf toe, rest and pain management is most beneficial for athletes. Without prevention of excessive extension of the great toe, symptoms of turf toe may disappear with rest just, to return once the athlete returns to activity.

Prophylactic Support

Athletes with turf toe may benefit from adding a steel or other stiff material insert into the forefoot of the shoes, to reduce extension. Taping of the great toe to prevent dorsiflexion may also be done.

Conclusions

Nearly all lower extremity injuries in athletes will benefit from rehabilitation programs that include therapeutic exercise. Restoring joint range of motion, muscle strength and neuromuscular coordination, should be emphasized, as should normal gait mechanics. A graduated return to physical activity that includes sports-specific exercises is recommended, with the primary goals being to allow a safe return to sport, while minimizing the risk of recurrent injuries.

I must make the point that the time to deal with any ankle injury is immediately following the injury! There are many degrees of ankle sprain and, as you have now read, many different types of ankle sprain treatments. Determining the injury type and severity will go a long way to ensure that your ankle recovers properly. As well, just because the swelling is going away and the pain decreases, does not imply that the ankle has healed properly. Loss of range of motion, scar tissue and persistent instability are all complications of ankle sprains – even minor ones.

Related Articles:

Chip Kelly Update: Everything's Good Again ...

Chip Kelly Update: Wailing and Gnashing of Teeth

Shock and Awe -- The Oregon Ducks' Football Hangover Effect

Despite Lopsided Score, Georgia State "Never Stopped Believing"

Hope Springs Eternal for Ducks

Incompetent Pac-12 Officials: How Do You Miss ALL of THIS?

NeuroDocDuck (Dr. Driesen) is a doctor who specializes in neurology, and sports medicine. He is an Oregon alumnus, completing his medical education and training in the UK. He has been both a practicing clinician and professor, a well-known and respected diagnostician, an author, and has appeared on national television.

NeuroDocDuck is active in his profession, and stays current on all new trends in his field. He enjoys golf and loves his Ducks!