The list of college coaches who have transitioned well to the professional level is not a long one, and shorter still is the list of those who have done well right away. Often it’s an inability to deal properly with professional players, other times the intense demands of the job are more than the coach is prepared for. Still other college-to-NFL transitions have fared poorly because the coaches could not effectively use the same schemes in the pros that had worked so well for them in college.

In the 1970’s for instance, Chuck Fairbanks tried to run the same wishbone offense in New England that had worked for him at Oklahoma, with less-than-stellar results. It’s no surprise then, that any time a college coach starts coaching on Sundays and brings his playbook with him, there will always be skeptics who say that a certain brand of football won’t work at the professional level.

Enter Chip Kelly.

One of the most common generalizations of Chip Kelly’s offense is that it’s a fad. Even smart, seasoned NFL coaches have made the mistake of dealing in platitudes and generalizations when discussing Kelly’s offense with those in the media.

Bruce Arians of the Cardinals said that Philadelphia had a great “college offense” before their contest in Week 13 of this season, and repeated the same old tired cliches about how quick the defenders are in the NFL and how you don’t want to get your quarterback hit. As it turns out, smart people can say some pretty dumb things sometimes.

College to NFL?

Elsewhere, the talking heads on ESPN and NFL broadcasts look at Kelly’s success with cautious optimism at best, commenting on its impressive production while peppering their remarks with statements about how the NFL is so much different than college, and that this style of offense has a limited life expectancy.

Worst of all are the comparisons to the Wildcat, which is a ridiculous analogy, as if Philly was lining up with LeSean McCoy in the gun all season with an unbalanced line and letting him run around with the ball, without any kind of rhyme or reason to the attack.

The reality is that Kelly does not simply have a collection of plays, he has an offense. What’s the difference?

Some coaches merely have a collection of plays that they really like. They may all be great ideas, but one does not complement the other very well, leaving room for the defense to easily anticipate what’s coming next. Contrast that with an offense, which has plays that complement one another, and provides a coach with clear alternatives if the defense is focusing too much on one thing.

Being able to draw up plays on a blackboard is one thing, but what happens in a game when their defensive end is a lot better than you realized, and you’re not able to run the ball to his side like you wanted? What happens when the opposition begins anticipating your favorite pass play and starts doubling your stud receiver? What’s your plan B? What are your answers? In football, almost nothing ever goes completely according to plan, so a coach without answers is a coach without an offense, and a coach without an offense will eventually become a coach without a job.

In contrast to this, Kelly’s offense is a well-oiled machine with plays that complement one another, with contingency plans built in. The keys to the system’s success are:

1. Simplicity.

Chip Kelly

Chip Kelly is all about keeping the playbook as thin as possible. Controlling the number of different schemes the players have to learn and internalize, not just at the beginning of camp, but from week to week, is essential to the coach’s philosophy that he developed at Oregon and in his earlier days at New Hampshire.

Doing so allows his players to think less and react more, which is always preferable. Along with limiting the amount of plays — contrary to the typical NFL playbook — Kelly’s lingo doesn’t usually descend into the kind of Shakespearean wordplay that comes with having calls like “Flip right double-X jet 36 counter naked waggle at seven X quarter.”

The large amount of carryover in schemes from week to week allows the Philadelphia offense to get better the longer the season goes on. It’s never a good thing when players have to learn a large amount of new plays each week, and in this way many coaches can be their own worst enemies.

Of course, Kelly adapts his offense to best attack that week’s opponent, and he’ll add a few wrinkles here and there to keep things fresh, but for the most part, the plays that Philadelphia installed during the first week of training camp were the same plays they used during the wildcard round, consisting of power zone running schemes, shallow crossing routes and effective use of screens.

2. Get the ball to your best athletes in space.

This philosophy has been one of the prime reasons so many coaches adopted different kinds of spread offenses over the past decade. The Eagles are not unique in this respect, since all coaches say they want to get the ball to their playmakers, but Kelly’s schemes have been fine tuned to use every inch, horizontally and vertically, of an NFL football field.

Philadelphia has the best pair of speedsters at the skill positions in the league, with McCoy and DeSean Jackson, and you can bet that a large portion of Kelly’s call sheet is taken up by plays designed to get them the ball.

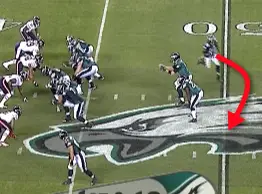

One of the most common concepts Kelly uses to get his two playmakers out in space is drawn up in the picture below.

An amalgamation of several different common NFL passing concepts, the play allows McCoy to run free up the sidelines against whichever opposing defender drew the short straw and was assigned to cover him out of the backfield. Not only that, but the tight end and slot receiver provide some great rub play (or pick play, if you’re a defensive coach) on the defenders in the box.

If the defense happens to play zone, and McCoy isn’t able to find room up the sideline, there’s still a high-low concept going on in the middle of the play with the basic cross at 12 yards, and the mesh and snag routes underneath forcing the defenders in the box to pick their poison.

If they simply drop back and defend the deep ball, Nick Foles will nickel and dime them until someone breaks a tackle and the home crowd is singing “Fly Eagles Fly” after another 7 points. If they come up to defend the shallow routes, then, well, see the previous sentence.

All of these concepts are designed with one thing in mind: to create space and separation for the offensive skills guys where before there was none. Kelly did a masterful job of it in 2013, and this team will only get better with another year of experience under its belt.

3. Put defenders in conflict.

In his book Swing Your Sword, Mike Leach talked about his philosophy on offense, which was all about putting defenders in a bind. This isn’t revolutionary by any means, but I really liked the way he put it:

If you have a 4.5-forty guy who hesitates, then he’s playing like a 4.9 guy. If another guy is a 4.7 guy but he reacts decisively at the snap of the ball, he’s probably moving like a 4.5 guy.”

Defensive coaches have a long list of pet peeves, but one of the biggest is playing slow. Many coaches even tell their players that if they’re going to make a mistake, do it fast. If you accidentally bite on a play fake, do it fast and get after the QB. One of the worst things you can do, on the other hand, is to spend too much time hesitating, because every second you’re not moving is another second of separation the offensive man is gaining on you.

Kelly’s schemes are designed to do just that. Besides being able to vertically and horizontally stretch defenses with pass patterns and create space where before there was an opposing defender, this offense does not allow the defense to be very decisive at all. For example, take a look at one of his most common screen plays used this past season in Philadelphia.

What we have here is a double screen, with both Jackson and McCoy, lining up on either side of Foles in the backfield.

Orbit route

Foles will put Jackson into an “orbit” motion behind him, sending him flaring out into the flat, and just after that he will snap the ball and fake it to McCoy, who is heading the opposite direction.

Foles will first read the edge defender to the flare side, and if he rushes up the field at the QB, or chases McCoy to the opposite side of the formation, Foles will toss it out to Jackson, giving one of the fastest men in the league all kinds of room to run and two blockers in front.

On the other hand, if one or more defenders widen with Jackson and chase the motion, Foles will look in his direction to pull the secondary with his eyes, then at the last moment turn the other way and get it to McCoy, who should be setting up a yard or two outside the offensive tackle with a wall of blockers in front of him.

This play is a perfect example of why the defense cannot be too aggressive, and as a result, cannot play very fast against this offense. As soon as you start to commit to what you think is happening, something else entirely develops on the other side of the play.

As we’ve seen from these examples, Chip Kelly is not introducing a trendy, statue-of-liberty-type offense to the NFL, he’s simply maximizing the opportunities for his guys to make plays. Whether the talking heads and “experts” will ever figure it out remains to be seen, but one thing is for sure, this style of play is here to stay.

__________

*In his defense, Arians is more concerned with learning the nuances of opponent defenses, since he calls the plays for Arizona, so he probably hadn’t seen a whole lot of film of Philadelphia’s offense. If he had taken the time to sit down and study the Eagles’ attack, it’s unlikely he would have made the same remarks.

Related Articles:

Alex Kirby (Writer and Football Analyst) worked several seasons as an assistant football coach at the high school and college levels and is the author of Speed Kills: Breaking Down the Chip Kelly Offense, now available HERE.