There’s a lot more to defensive football than many people realize, as this isn’t a little kid’s soccer game with a herd of midgets chasing the ball. What coaches refer to as run fits are more like a well-choreographed dance. Run fits are the defensive responsibilities given to particular players in attacking a blocker or ball carrier either to the inside or outside. While that is a mouthful, I will make it simple for you and thus you will learn some important defensive concepts from your Oregon Ducks in how they stopped the Outside Zone plays of Texas.

Each defender has a job to do. More like two jobs — and which one to perform will depend on the offense’s call – run or pass. The defender has a key — an opposing offensive player – and based upon what that player (or players) does (or do), he gets a read that tells him what type of play is being called.

To go into the keys and reads of each defender of Oregon’s 3-4 Defense would take some time. While the defense is not extremely complex by NCAA Football standards, there’s much more than meets the eye for a casual fan.

When the defense reads a run play, each player executes his techniques for defending the run. The collective effort of all 11 defenders on the field creates your run fit. If just one player on the defense doesn’t do his job, and do it well, the result is going to be a positive offensive play.

But when all 11 Ducks defenders execute their jobs to perfection … man, it is a thing of beauty!

What are Run Fits?

Let’s get into a little terminology here, and do keep in mind that terminology in football is not universal. You may hear other coaches use very different phrases, but I’ll touch on some of the most common ones that you will see in Oregon’s defense.

That Oregon’s new Defensive Coordinator, Don Pellum, was an in-house hire is a big benefit in that regard, since players won’t have to learn new schemes and terminology. Instead they can focus on improving their reads and techniques, building on the solid foundation that has already been laid.

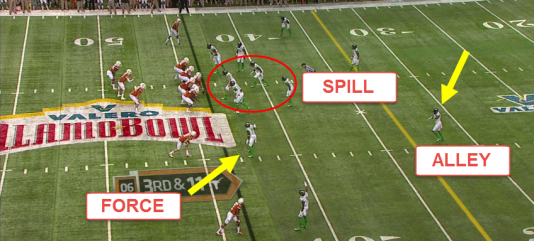

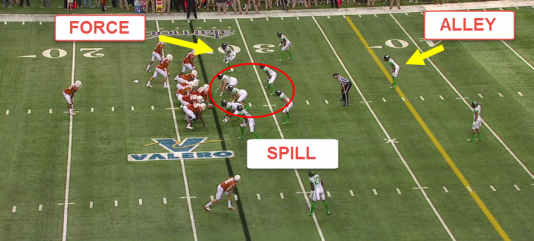

Run defense responsibilities can be loosely grouped into three primary job categories before the snap. In the image above, the interior defenders (Red circle above) are the spill players, preventing the ball carrier from running the ball inside. They include No. 44 DeForest Buckner and he will be the one to eventually make the tackle.

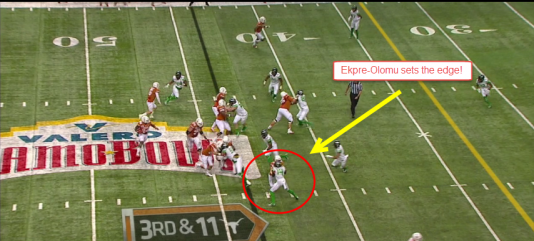

Ifo Ekpre-Olomu, No. 14, is the force player above on a 3rd-and-11 against Texas (Oregon has extra DB’s on the field for 3rd-and-long). Ifo’s job is to set the edge for the defense, and turn the football back inside to the spill players.

The man that ties everything together is the alley player, No. 21 Avery Patterson. He will fit (position himself or fill) between the widest spill player, and the force player. It’s possible that on paper, Patterson was initially the force player, but as the play unfolded, Ekpre-Olomu ended up in a position to force the ball.

Remember that these are jobs for the defenders, not positions. Who will be responsible for each job is dependent on a number of factors. Let’s take a look at each of these responsibilities in more depth.

Spill Players

The spill defenders work to make the ball carrier run laterally, taking away any North-South running lanes. As long as the ball is moving side to side, the offense isn’t gaining any yards. Spill players will attack the inside half of ball carriers and lead blockers to get the job done – Defensive Linemen and Inside Linebackers are almost always spill players.

Force Players

Force defenders attack the outside half of ball carriers and lead blockers, as they are trying to turn the ball carrier back inside to the spill players. There is one force player on each side of the defense, as either an Outside Linebacker, Safety, or Cornerback will be the force player (That assignment is determined by the coverage called).

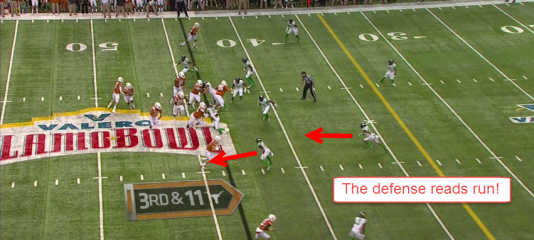

When Ekpre-Olomu diagnoses outside run to his side in the image above, he knows he has to force the play back inside.

A key to being a force player (also known as a box player or contain player) is to keep your shoulders square to the line of scrimmage, and keep your outside arm and leg free. He must force a change of direction for the ball carrier.

In the image below, Ekpre-Olomu diagnoses the run and immediately attacks the outside half of the Texas receiver. He has to really attack the blocker to set a hard edge for the defense.

Simply being outside is not enough, because if he fits (contains or positions himself) too wide — a running lane is opened up between him and the spill players.

Alley Player

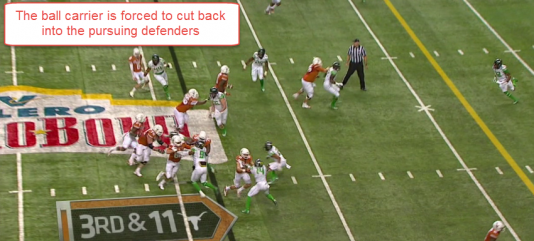

The alley defender is fit (positioned) between the widest spill player and the force player. The alley player caps (takes head-on) the ball carrier, fitting head up on him on an outside run play. The alley player is also a safety valve in case the force player gets caught inside. If that happens, he will adjust his fit (responsibility) to replace the force.

Notice Patterson’s fit in the image below (He is just above and to the right of No. 14, Ekpre-Olomu). He is just inside of the hard edge that Ekpre-Olomu has set, and thus there’s no air between the widest spill player and the force player, because Patterson has capped it. (Mr. FishDuck note: memorize that last sentence and repeat it to others and you will sound VERY football-savvy)

Not all defensive calls have a clearly defined alley player, but when they do it is normally the Free Safety in a Cover 1 or Cover 3 defense.

Secondary Force Players

Any pass-first defenders who are not involved in the primary run fits are secondary force players such as corners that are playing a deep zone, or playing in man coverage, and hence are secondary contain defenders. They do not get involved in defending the run until the ball carrier crosses the line of scrimmage and trick plays like a Halfback Pass are no longer a threat.

Secondary Force (or secondary contain) also will fit in a running play if the outside receiver he is covering does a crack-back block on the force player. In that case, he executes a crack-replace technique, taking over the job of the force player who has been crack blocked.

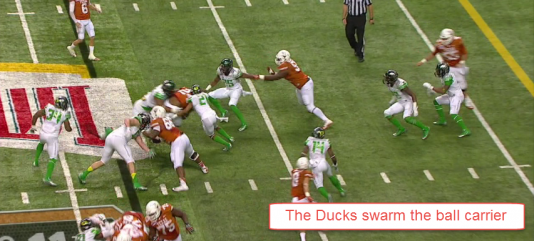

After the start of the play, the corner at the bottom of the picture is gone. He’s the secondary force player pass covering deep and doesn’t get involved on the play. Due to the great force job by Ekpre-Olomu and the perfect alley position of Patterson, the ball carrier had no choice but to cut it back into the relentless pursuit of spill defender Buckner.

The Outside Linebackers in the Ducks’ 3-4 Defense can be either a spill, or force player. It all depends on the coverage called, as coverage determines the run fits for a defensive play. Defenders that are responsible for the flats in a zone coverage are usually the force player. Defensive Coordinators always have to match the coverage called to the defensive front for the pieces of the puzzle to all fit together.

When all the Oregon players carry out their run fit, the result is a stuffed Outside Zone play (above) for the Longhorns. Each Duck defender knows his role as spill, force, or alley player and executes superb technique to defeat the much larger Texas offensive line.

The Choreographed Dance

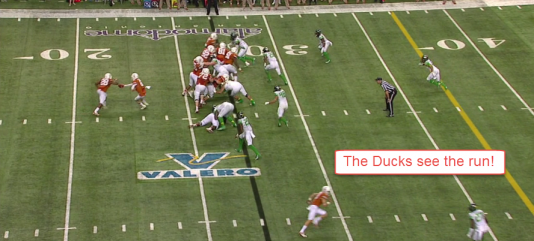

In another play from the same game, Texas (below) has a 1st-and-10 from their own 27 yard line in the 3rd quarter. They have a bunch formation to the left, a favorite formation for Offensive Coordinators to call outside running plays into.

Above, you see No. 91 Tony Washington walked outside of the point man, the receiver in the bunch set who is up on the line of scrimmage. Washington will be the force player.

Brian Jackson, No. 12, is the safety on the 3-receiver side and is responsible for running the alley. The spill defenders are the Defensive Linemen and Inside Linebackers and that group includes No. 66 Taylor Hart, the eventual tackler.

As the Oregon defense sees the run play, the spill players and force player are very fast to react. The Corner, who has secondary force, squats and is much more patient. Remember that his job is still pass first and he cannot jump the run until he’s absolutely sure.

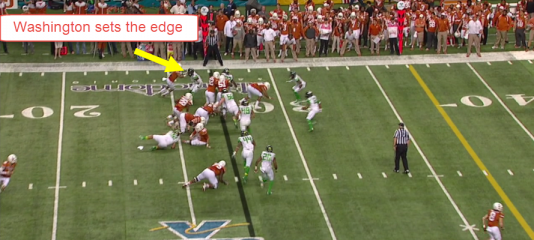

Washington does a fantastic job of setting the hard edge and forcing the play inside. He attacks the point receiver, knowing that if the outside receiver were to come down hard on him, it would trigger the secondary force player to fit outside of him and become the force defender.

With the wall of Duck defenders built, Hart is able to run down the Texas ball carrier from behind for a short, 2-yard gain.

We featured this play in an analysis of Taylor Hart recently from a defensive line technique perspective. This new analysis you are reading has enabled you to see the defensive responsibilities, or the run fits by the Oregon defense that made his tackle as a spill defender possible.

Reading through this can get a little tricky at first, but once you understand these terms and defensive responsibilities, it will increase your enjoyment of Oregon’s 3-4 defense that much more. This begins to provide a defensive background of run fits that will serve you well as you watch so many great running opponents on your schedule. There is plenty more to learn about 3-4 defensive concepts, and I look forward to unfolding them for the special readers of FishDuck.com.

I may be in Virginia, but “Oh, how we love to learn about your beloved Ducks!”

Coach Joe Daniel

Richmond, Virginia

Website: http://football-defense.com

Twitter: @footballinfo (http://twitter.com/footballinfo)

Facebook: http://facebook.com/footballdefense

Joe Daniel (Football Analyst) is the author of Football-Defense.com and Football-Offense.com, and host of The Football Coaching Podcast. Coach Daniel has written over 300 articles and produced six eBooks on coaching football. With 10 years in coaching both High School and College Football, he will be the Defensive Coordinator for Prince George High School in Prince George, Virginia for the 2012 season.