It had been a time of great suffering, 26 years to be exact, since Oregon had last played in a bowl game. There had been opportunities, but the heartbreaking trend known as “Duck-Luck” repeatedly reared its ugly head preventing Oregon from elevating itself above the mire; unfortunate injures or odd circumstance always getting in the way. For a time Oregon had been so bad that there was talk of kicking the Ducks out of the Pac-10 conference entirely.

Yet by the mid-80s things looked to be slowly improving, Oregon had talented players that would go on to fruitful NFL careers, particularly the 1986 recruiting class that included names like Derek Loville, Terry Obee, Tony Hargain, Chris Oldham, and a lanky quarterback from Colorado named Bill Musgrave. ‘Duck-Luck’ would continue to haunt Oregon though, as in 1988 a then 6-1 Oregon team failed to win another game in the regular season after Musgrave broke his collarbone vs. ASU, leaving the Ducks once more just out of reach of a bowl game.

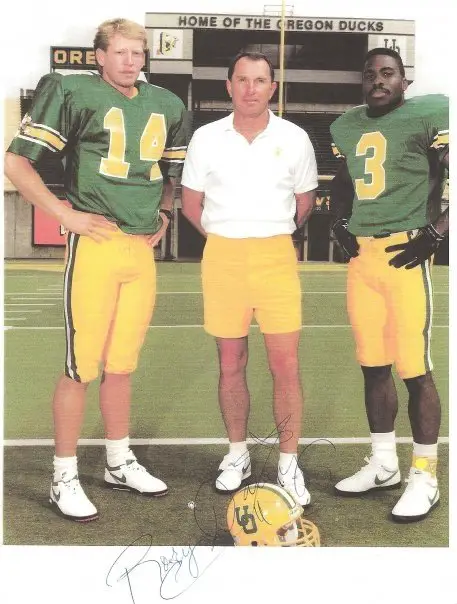

Quarterback Bill Musgrave (left), Head Coach Rich Brooks (center), and safety Rory Dairy (right) spearheaded Oregon’s return to prominence in the late 1980’s.

For the players, it was agreed that it was time to put the bickering and me-first attitudes aside and overcome the long-standing adversity as a team. They did so in 1989, becoming bowl eligible and defeating the Tulsa Golden Hurricane in the Independence Bowl in one of the coldest games any of the participants can ever recall.

In the context of the 1989 football season there was little reason for the public to pay much attention to the two small schools playing in some minor bowl game, but the game would set in motion a transformation of one program to national title contender, while the other would continue its toil in obscurity. At first, despite being bowl eligible, Oregon wasn’t even going to be included, until the University guaranteed to purchase a certain amount of tickets for the game in advance to entice the bowl committee to agree on an Oregon invite. It ensured that the school would likely lose money on the venture, but the pride involved in Oregon finally after long last returning to a bowl game was far more important than any measured dollar amount.

At the time, the Oregon and Tulsa programs were practically mirror images of each other. Both had spent years out of sight out of mind entrenched in a long bowl drought, both struggled to recruit in nearby fertile recruiting grounds having to largely settle for the leftover scraps not consumed by the major conference teams nearby, both had geographic and financial disadvantages. Most of all both programs had a sensation of being perennially snake-bitten, Tulsa also owning a share of the so-called ‘Duck-Luck’ that everyone could sense looming just over the horizon whenever it seemed like things might finally be turning around.

If there was an advantage, it was Oregon’s connection with the Pac-10 conference while Tulsa was an independent, Oregon’s slightly larger enrollment, and Oregon’s coaching staff longevity, while head men at Tulsa viewed their positions as a stepping stone leaving for bigger jobs at the first offer causing almost annual turnover in their staff.

Oregon finished the 1989 regular season with a 7-4 record, Tulsa 6-5; both teams had finally made it over the hump to a bowl game, both hungry to change their losing traditions.

But would you believe that the thing that led Oregon to victory that chilly night in Shreveport, LA in the 1989 Independence Bowl was a pair of hand-me-down black shoes?

To the victor went the spoils, as in the time since Oregon’s narrow 27-24 victory that night, the Ducks have elevated step-by-step to more bowl games, improved facilities and recruiting, national prominence, and a shot at the national championship; while Tulsa descended into a long string of losing seasons until their own recent still-in-progress rise to redemption. Could it be that the difference between one program’s meteoric rise to glory and the other’s downfall was sparked by a pair of cleats? At a school now commonly referred to as “Nike U,” perhaps it is fitting that something as simple as footwear could indeed start a revolution.

Was Nike inspired to make its iconic early 90s “It’s Gotta Be Da Shoes” ad campaign because of the 1989 Oregon Ducks football team? Only Uncle Phil knows for sure…

The Tulsa Golden Hurricane was a team led by a superstar destined for greatness, wide receiver Dan Bitson. Bitson led the nation in receiving yardage, an unstoppable force putting up gaudy stats every game, it was easy to predict a long NFL career was in his future. He was a Parade All-American and projected early NFL draft choice if he chose to come out early.

“Dan could do anything, so much of our offense was built on just getting the ball in his hands and figuring things out from there,” said Gary Treat, in 1989 the starting senior tight end and co-captain for the Tulsa Golden Hurricane. “When he was on the field nobody could catch him, he couldn’t be tackled, just a great open field runner. He single-handedly won games for us that year, we had a good team but everything was built around him first.”

Tulsa wide receiver Dan Bitson was a Parade All-American, leading the nation in receiving, but a tragic car accident would cut his career short.

Bitson jumped off the film when Oregon prepped for the matchup against Tulsa in the Independence Bowl. “We saw the film on Bitson and he was an absolute beast, the whole defensive gameplan was built around stopping him,” Rory Dairy recalls, then a junior strong safety for Oregon. “We were going to have Chris (Oldham) shadow him all game and I was going to play over the top in a robber technique, everything was built on just trying to cover that guy.”

However, 12 days before the big game both teams would have to scrap their entire game plans, as Dan Bitson’s life would be forever changed in a car accident just a few blocks away from Tulsa’s Skelly Stadium, shattering his body so severely he spent 49 days in the hospital recovering and for a time wondering if he would ever walk again, his shot at an NFL career destroyed.

Information of Dan Bitson’s horrific car accident is detailed here: http://articles.latimes.com/1991-12-27/sports/sp-1068_1_play-football

“Our entire game plan had been built on stopping their wide receiver, so going into the bowl game now we had no clue what Tulsa would do,” Dairy recalls. “We couldn’t notice anything on film because their offense was all about that guy, so we went into the bowl game blind and just had to feel them out.”

“As a fellow receiver, I felt so bad for him that Bitson got hurt that badly right before the ball game,” Tony Hargain remembers, a starting junior wide receiver for Oregon in 1989 who would go on to an NFL career with the 49ers and Chiefs.

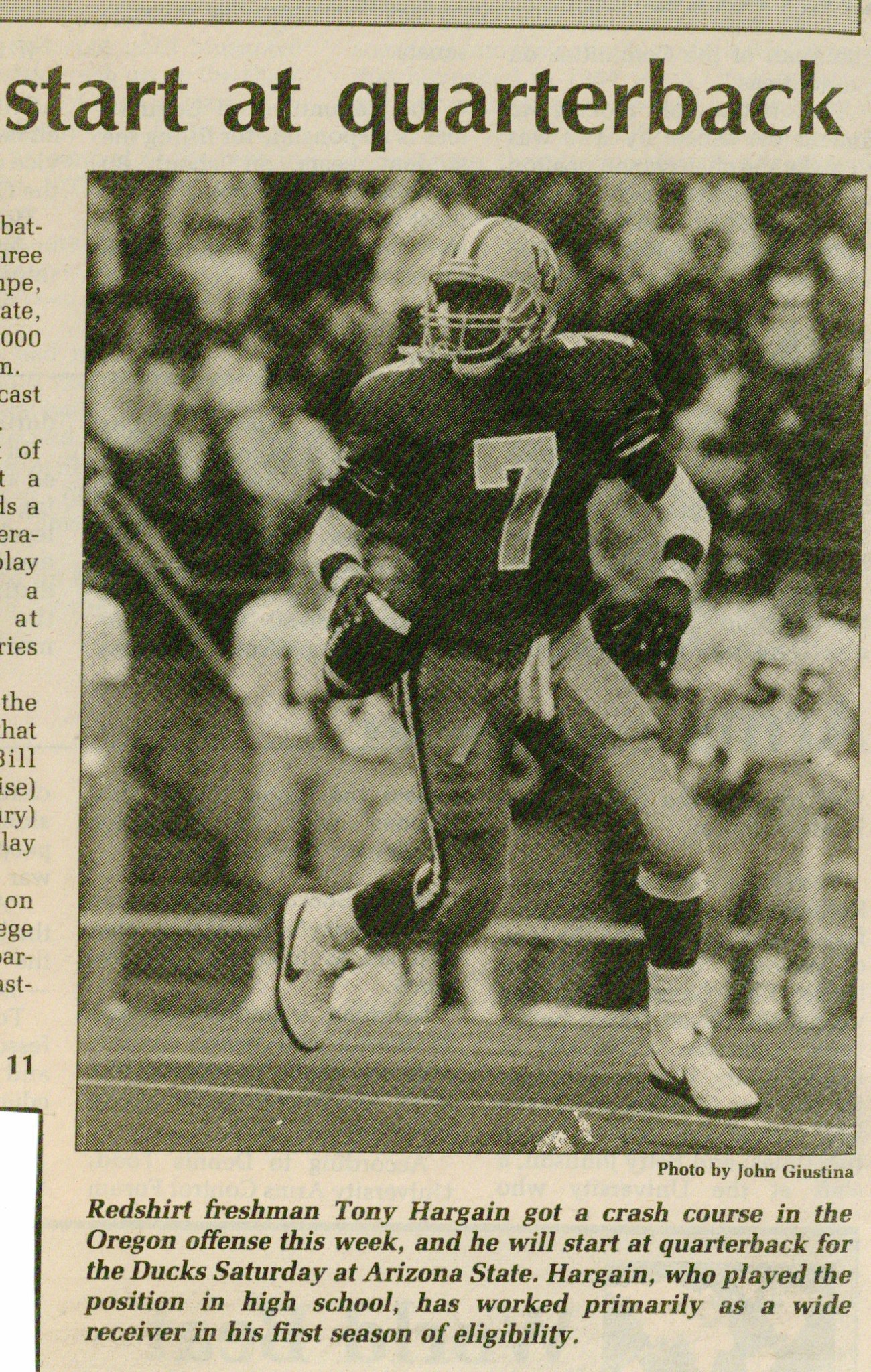

Oregon wide receiver Tony Hargain was a versatile weapon for Oregon, even playing quarterback for a couple games in 1987 due to attrition at the position.

“We had to change our whole game plan, we were totally behind the 8-ball and mentally devastated,” said Gary Treat, reflecting on Bitson’s accident. “We decided to instead concentrate on the running game and underneath passes to attack with Bitson out. Coaches came up with a great game plan to be more balanced than we had all season long, control the ball and the clock. I don’t know if the game would have turned out differently if Dan hadn’t had his car accident, but everyone knew our team was built around Dan, losing him was a huge blow.”

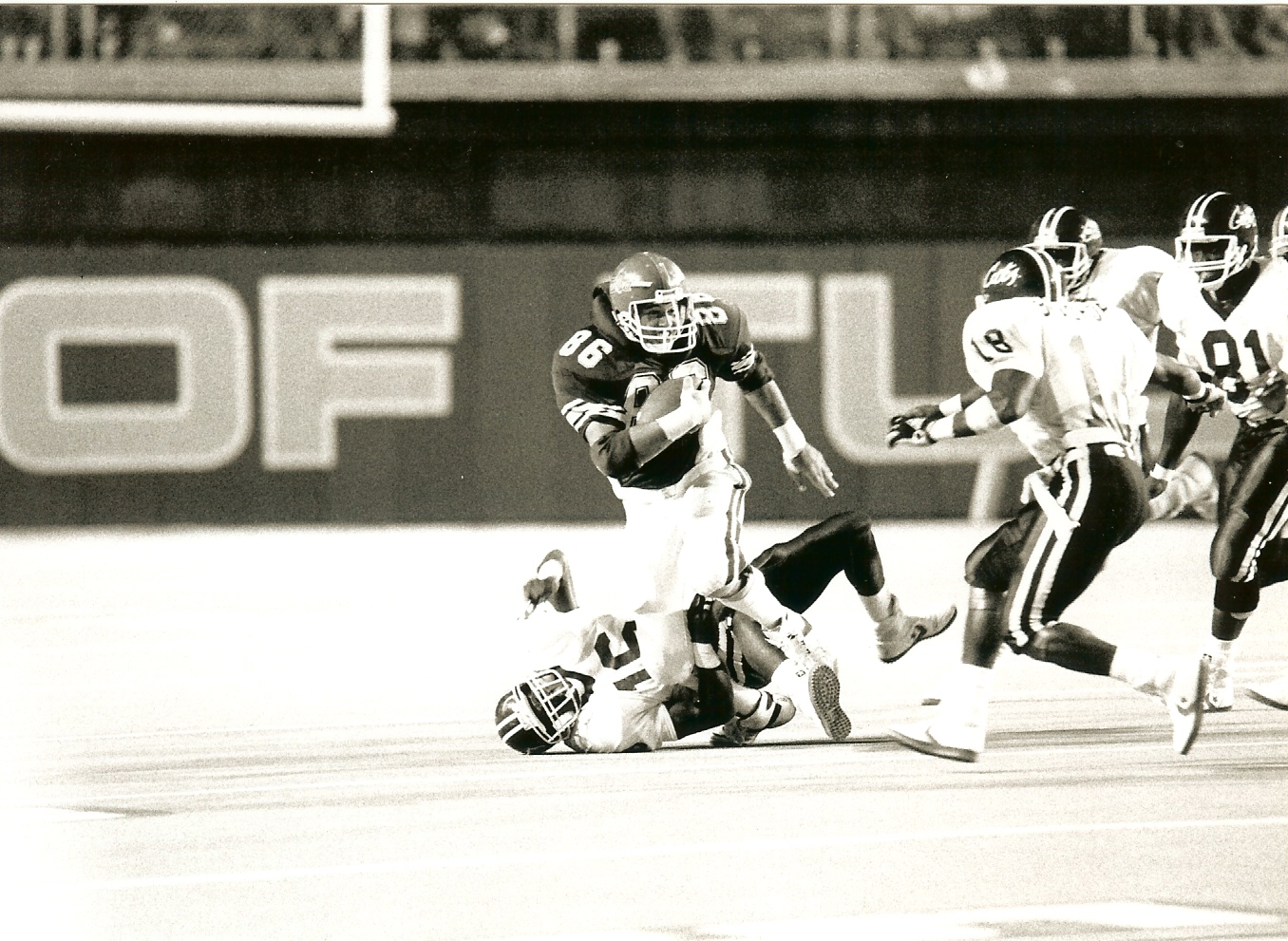

Gary Treat (#86) was a co-team captain his senior year in 1989 as the starting tight end for the Tulsa Golden Hurricane.

Oregon had turned the tide of losing seasons to reach the bowl game, and during preparation for it in practice the players decided they wanted to start their own traditions to keep the good times coming.

“Everyone was so excited just to be a part of the festivities; the pep rally, and being able to practice more after the season was such a big deal,” said Dairy. “We were having so much fun practicing getting prepped for that bowl game, we decided that we should start our own tradition. ‘From now on let’s go to bowl games every year, let’s get family and friends to come to Oregon, let’s make this real. Let’s do anything we can to make sure this happens again and again.’ We all collectively agreed.”

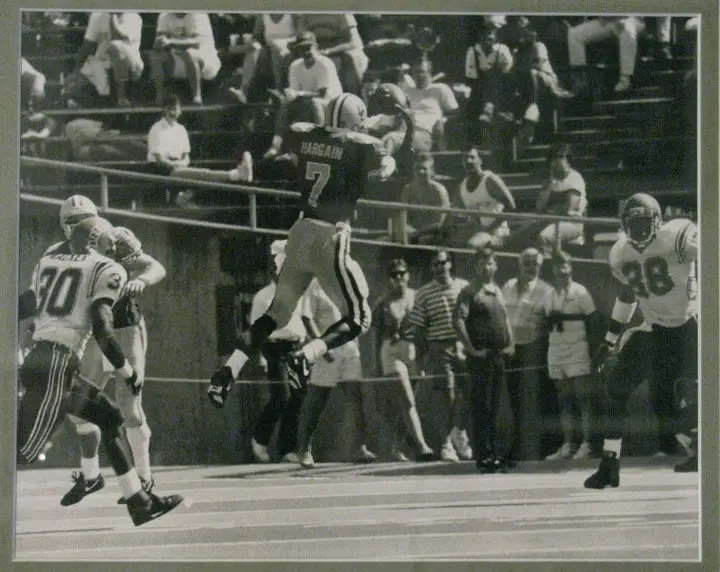

Oregon players, including Rory Dairy (#3-middle), had big aspirations for the Ducks.

Tony Hargain also remembers the preparation for the Independence Bowl, “The main thing was we hadn’t been in a bowl game in almost 30 years, we were all so excited to be the ones that did that. Before that 1986 class the team wasn’t usually winning more than 2 or 3 games a year, it was a big deal for us that we were the ones changing things in Eugene.”

Oregon wide receiver Tony Hargain became a reliable target for Bill Musgrave, and would be a key weapon in the 1989 Independence Bowl.

Part of starting that tradition meant changing the look of Oregon. Head Coach Rich Brooks was a stickler for team unity, no dancing or showboating, nothing to draw attention to yourself, a team game requires a total team effort to win.

“You are a spoke in the wheel,” Coach Brooks would repeatedly tell his players, preaching to know your role and do your job, trusting that those around you will do theirs. This team unity concept heralded by Brooks was a top-to-bottom ideology, which included a very specific look for uniforms. Every player was to dress the same, including wearing white cleats. Starters were given two pairs of white shoes, reserves would receive only one pair. Odd to think that at the school where Nike was founded footwear for athletes was both scarce and bland.

“Part of our pact of starting our own tradition was getting our own gear, we decided enough was enough,” Dairy recalls. “My godfather Robin Cole had played in the NFL with the Steelers, and his brother Dennis gave me a pair of his old cleats from when the Steelers won the Super Bowl in 1979. I took those black cleats with me to Oregon, but I never wore them until the Independence Bowl. I decided I was going to break them out for that game. All the guys saw them and wanted black cleats too, so everybody spray-painted their white cleats black the night before the game.

Some of the guys painted their shoes green, Derek (Loville) and Daryl Reed made theirs green, but most went black. Coach Brooks was so conservative about such things he never would have approved it, so we hid them from him. But a few of us put on our cleats for pregame warm-ups and he saw them, so when we all headed back into the locker room he was livid.”

“If this wasn’t a bowl game all of you wearing black shoes would be [expletive] benched!’ coach Brooks screamed.

“Can you imagine a game where Derek Loville, Terry Obee, Latin Berry, Eric Castle, Chris Oldham…half the starting roster for Oregon wouldn’t be playing in the first bowl game in 27 years just because we wore black shoes?” Dairy remembers, laughing hysterically.

Dairy continued, “Coach was furious. He chewed us out so bad I could see guys hearts beating out their chests through their shoulder pads, he was that mad.”

Then Coach Brooks paused, and asked the team ‘ok, how many of you guys painted your shoes black?’ About 2/3s of the team sheepishly raised their hands.

Enraged, Brooks asked the equipment managers if they had enough white cleats for the whole team, they responded no. Growing even more frustrated, Brooks realized he couldn’t bench almost the entire team for the bowl game, so he compromised.

“Ok, you can wear the black shoes, but you better win or there will be hell to pay!” Coach Brooks shouted as he started to storm out of the locker room. The players knew he meant it too, and they would do anything to avoid the ultimate wrath of their head coach, a strict disciplinarian with a reputation for severe punishments if players messed up.

They knew they had to win at all cost. As Coach Brooks was leaving to regain his composure, one of the underclassmen offensive linemen raised his hand again and asked, “Coach, if we win, can we have black shoes next year?”

The team’s lifted spirits from their personalized footwear was somewhat dashed by the poor weather conditions that worsened at game time. Freezing cold, heavy rain, and strong winds made the game a miserable experience for everyone in attendance.

Players and fans tried anything to keep warm during the 1989 Independence Bowl, but little helped to quell the freezing rain and wind. Notice the Oregon Ducks various shoe colors, and Tulsa TE Gary Treat #86 winning the coin toss.

“In Tulsa by late November we’d get a lot of snow, so we had played in cold games before, but I have never been as cold in my life as I was during that entire game,” Gary Treat recalls. “It rained a lot that game, and it was freezing, the wind was blowing. Everyone was wet the whole time, and when you’re soaking wet with the wind blowing it just made for a miserable experience. Everybody huddled around the heaters, but it didn’t help much.”

“Man, some guys actually melted their cleats getting too close to the heaters,” Dairy laughed. “Our motto back in those days on defense was 3-and-done, but that was the only game I ever recall hearing our guys saying that they hoped they would have long drives and score on us just so that we could stay out there running around as it was the only way to stay remotely warm.”

“I actually wasn’t that cold, or maybe I was just so focused on the game I didn’t notice it,” Tony Hargain boasted, “but after the game, yeah I was pretty cold.”

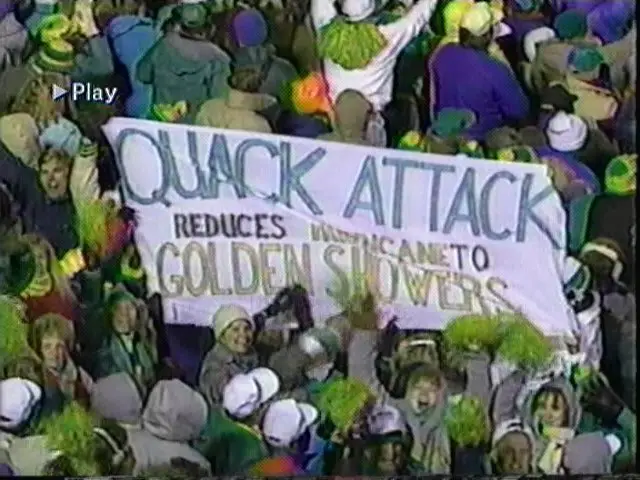

Oregon fans kept their spirits high through freezing conditions at the 1989 Independence Bowl.

Rory Dairy continued, “I can’t imagine how terrible it must have been in the stands, the fans that came out to support us were fantastic, the ones who stayed at the game and hounded it out in that miserable weather and tasted victory at the end with us, I give them the utmost praise and thanks. We were so thankful for them hammering it out with us, but I never wanted to play in a game like that again.”

Despite the frigid conditions, Oregon fans came to Shreveport, LA in droves to cheer on the Ducks with the tongue-in-cheek humor, passion, and boisterous spirit that has made Duck fans world-renowned.

Much of the first half was controlled by Tulsa, dinking and dunking their way down the field moving the chains on Oregon’s defense a couple yards per play.

“They dominated us at the start,” Dairy recalled. “We didn’t get a chance to shine much because our defense was on the field for most of the first half. At key times we made plays, but we never really got our offense going. They outflanked us a couple times, but our D never broke, we never even bent, it was all short plays moving the chains.”

Tulsa looked to take the early lead on their opening drive, but Oregon all-american cornerback Chris Oldham intercepted a pass in the endzone from Tulsa QB T.J. Rubley to give the ball back to the Duck offense.

Oregon cornerback Chris Oldham intercepts a pass in the endzone on Tulsa’s opening drive, a play that would set the tone of the game; Oregon taking advantage of Tulsa mistakes at key moments.

“That play by Chris (Oldham) was huge, it was such a relief,” said Dairy. “When Chris made that pick it felt like the Duck-Luck had perhaps finally been broken, that gave us a lot of confidence.”

Oregon got a couple big plays but couldn’t find consistency to string together drives in the cold conditions, giving the ball back to Tulsa to once again slowly drive down the field.

It wasn’t until late in the first quarter when Oregon got the ball moving, when Musgrave found Tony Hargain on a deep curl for a big gain.

“Tulsa wasn’t doing anything special to shut us down, we just started off the game kind of slow,” said Hargain. “There were a couple dropped passes and we just weren’t moving the ball. That curl pass I caught really loosened things up, it broke the ice. That got us into the flow of the game.”

Oregon wide receiver Tony Hargain catches a pass from Bill Musgrave and is a step away from breaking it for a touchdown during the first half vs. Tulsa.

Shortly afterward wide receiver Terry Obee made a big play on a reverse, setting up Oregon for a field goal.

Oregon wide receiver Terry Obee picks up a big gain on a reverse.

By the second quarter Tulsa maintained a 7-3 lead with their slow-crawl offensive game plan, but the Oregon defense was making it tough.

Oregon safety Rory Dairy was a key cog in the Oregon defense, here tackling Tulsa RB Brett Adams for a 4-yard loss.

Oregon cornerback Chris Oldham was almost single-handedly keeping Oregon in the game, again intercepting a pass when Tulsa tried to strike over the top into the windy conditions.

Oregon cornerback Chris Oldham gets his second interception of the game vs. Tulsa.

Oregon immediately capitalized on the turnover, playing with the wind in the 2nd quarter Oregon quarterback Bill Musgrave threw deep to reliable receiver Joe Reitzug for a huge gain setting up the Ducks with their first realistic redzone scoring opportunity.

Oregon wide receiver Joe Reitzug had a flare for the dramatic, his whole career making spectacular acrobatic catches like this one vs. Tulsa.

Oregon quickly hit paydirt, with wide receiver Tony Hargain spinning out of a tackle and sprinting for the goal line, giving Oregon the lead for the first time in the game, 10-7.

Oregon wide receiver Tony Hargain makes a great spin move and sprints for the goal line for Oregon’s first touchdown of the game.

A blocked punt by Tulsa returned for a touchdown would give the Golden Hurricane the halftime edge 17-10, with both teams sprinting for shelter to the locker rooms to thaw out from the cold and wet conditions.

“At halftime coaches made the adjustment to come up and attack more, knowing Tulsa was trying to beat us with short plays,” Dairy remembers. “We knew if we could force 2nd and long or 3rd and long we could get our offense the ball, but if we let them cut us up with these short plays setting up short yardage they were going to beat us.”

“We wanted to be more aggressive in the second half,” said Hargain. “Joe (Reitzug) came up with some big catches, and Bill (Musgrave) was getting into a good rhythm moving us down the field. We just wanted to attack more than we had, get the ball in the air.”

“We really had every opportunity to win the game,” Gary Treat groaned. “At the time I had a gut feeling that Oregon was somehow going to steal it from us, because we didn’t have the firepower. We were moving the ball and controlling the clock, but a couple turnovers were going to come back to bite us. I knew we hadn’t executed right, we gave up the ball too many times. I give credit to Oregon stepping up and taking it away, but I remember being up by 14 late in the game and feeling like we were going to lose.”

Tulsa TE Gary Treat was expected to be a big part of the game plan with superstar WR Dan Bitson out of the game with major injuries suffered in a car accident.

Tulsa continued their game plan in the 2nd half, adding an additional touchdown to make it 24-10 in the 3rd quarter until Oregon finally started coming alive. In a six minute span stretching into the 4th quarter the Ducks tacked on two touchdowns, first a 9-yard throw to WR Joe Reitzug and then a QB sneak by Bill Musgrave, his first rushing touchdown of his career, to tie the game 24-24.

QB Bill Musgrave throws to WR Joe Reitzug for a 9-yard touchdown to make the score 24-17 late in the third quarter vs. Tulsa.

Oregon QB Bill Musgrave runs for a touchdown to tie the score 24-24 in the Independence Bowl.

It was now up to the Oregon defense to find a way to hold Tulsa. The Ducks had managed to force several turnovers, but Tulsa had moved the ball well all game long.

The game-changing moment would come at midfield, as Tulsa decided to go for it on 4th and short running behind big Gary Treat with tailback Brett Adams, but Oregon LB Mark Kearns came flying into the hole to hold him at the line of scrimmage. The referees measured, and it was just short, Oregon ball.

A couple links of the chain swung the momentum decidedly in Oregon’s favor on this 4th down stop.

Oregon drove down the field to the 1 yard line, but were stopped twice setting up 3rd and goal. Controversy ensued when Musgrave’s foot got caught in the turf as he moved backwards to hand it off, fumbling the ball with a Tulsa defender quickly recovering it. The referees ruled that Musgrave’s knee was down before the fumble, Oregon maintained possession and kicked a field goal to take the lead 27-24.

Did Bill Musgrave fumble, or was his knee down before the ball came out? The Ducks’ would score the game-winning field goal on the next play, capping Oregon’s remarkable comeback in the 1989 Independence Bowl, a win that catapulted Oregon on a path to national prominence while dropping Tulsa back down into the category of also-ran’s.

“He absolutely fumbled, Musgrave absolutely fumbled!” Treat emphatically stated. “It was a horrible call, it’s maybe not what cost us the game, but yeah it hurt. Oregon got the ball back to take the lead, we still had our chance but that fumble call didn’t help.”

Tulsa would get the ball back to try to win it in one final drive, but without their all-world wide receiver Dan Bitson, driving the field with little time left was a tall order.

“We had turned the ball over and missed chances, definitely hadn’t played our best game,” said Treat. “We knew we had to put up some points because Oregon had an explosive offense, and if we let them hang around it would bite us.”

A series of big defensive plays set up a 4th and long, Tulsa needing to convert to keep their chance of victory alive. Tulsa QB T.J. Rubley dropped back, then inexplicably started running backwards some 20-30 yards eluding pursuing defenders before eventually being taken down.

Tulsa QB T.J. Rubley’s last-gasp effort was an odd one, ending in a sack on 4th down giving Oregon the 27-24 victory in the 1989 Independence Bowl.

“Heh, we called that the Rubley Shuffle,” said Treat, chuckling about the strange play that ended Tulsa’s chances of a comeback. “T.J. actually did that a lot during the season, he’d run backwards a ways and make so many guys miss eventually he’d somehow turn it into a gain or usually throw it away. Whenever it happened coaches preached to come back to the ball, but usually I’d start running deep because T.J. had such a cannon for an arm, he could chuck it 75 yards easy. I remember sometimes he’d do his shuffle going backwards, I’d release deep, and he’d overthrow me out the back of the endzone. He wasn’t a fast quarterback, but somehow when he started doing the Rubley Shuffle nobody could catch him.”

But Rubley was caught, eventually, and following an Oregon kneel down the Ducks victory was complete. The players celebrated with the fans that had stuck through the horrible weather, then rushed into the locker rooms to escape the bitter cold.

“Knowing that we not only made it to a bowl game but won was huge for us,” said Hargain. “Looking back to that 1989 team and 1986 class knowing that we had finally turned things around was a great source of pride.”

“When we won we were all back in the locker room jumping around chanting ‘We’re gonna get black shoes next year! We’re gonna get black shoes next year!’ For us that was a huge deal,” laughed Dairy.

Perhaps in the corner taking notes was then first-year offensive coordinator Mike Bellotti, recognizing that something as trivial as a little originality in uniforms could loosen up players and motivate them. Changing uniforms would become a trademark for Oregon on an almost annual basis starting in 1995 when Bellotti became head coach, a trend that has continued to this day in sharp contrast to the strict uniform specifications demanded under Rich Brooks.

“I do remember that my senior year (1990) for the first time we were issued black cleats,” said Tony Hargain. Coach Brooks may have been strict, but he was fair, and a man of his word.

The shoes would stay, as would other small changes. Something as simple as one hand-me-down pair of old black shoes had inspired others to follow the trend, to find an identity for Oregon and start their own traditions. In the coming years coaches would relax a bit, trusting players more for their own accountability, originality, and listening to their ideas. Players would form tight family bonds that remain today, and convince others to come to Oregon, establishing the talent pool that propelled the Ducks to its success in the coming seasons. Not a bad legacy to leave behind for an old long-forgotten pair of black NFL Super Bowl cleats.

As for Tulsa, they would get a small taste of redemption, winning the 1991 Freedom Bowl, but the revolving door of coaches and difficulty in recruiting would catch up to the program as the 90s would spawn 11 consecutive losing seasons.

“That was tough, losing in my last game,” reflected Gary Treat, who never got a chance to play in the professional ranks following the Independence Bowl. “But I’m proud of that team, we didn’t have Bitson but we fought hard, things just didn’t roll our way. I got to be a team captain on the first Tulsa team to go to a bowl game in 13 years though, and that’s pretty cool.”

Gary Treat (#86) never got a shot to play in the pros, but did earn a role as co-captain of the Tulsa Golden Hurricane his senior year.

Eventually Tulsa would start to turn it around in the early 2000’s, running a new spread attack offense long before it became the popular trend in college football. Led by then head coach Steve Kragthorpe (who later went on to become Louisville’s head coach, and would have been LSU’s offensive coordinator in Oregon’s matchup with the Tigers September 3rd if not for a recent diagnosis of Parkinsons Disease that has forced Kragthorpe to step down), Tulsa led the nation in total offense in 2003 and 2004. They repeated this feat again in 2008 and 2009, becoming the first school in NCAA history to lead the nation in total offense in successive years on two separate occasions. Tulsa was playing in bowl games again and making its mark, including last season’s shocking victory over Notre Dame and the dismantling of Hawaii in the Hawaii Bowl, 62-35.

Yet Tulsa remains a program unable to take the next step above that of mid-major juggernaut into the primetime the way that Oregon has in the years since the 1989 Independence Bowl. It is easy to ponder the what-ifs though…had Bitson not been injured, had Oregon not stopped Tulsa on 4th down, had Musgrave’s fumble been ruled a fumble–had any of these circumstances that swung the game in Oregon’s favor instead gone Tulsa’s way, would it be Tulsa that followed the path Oregon has ascended for the past 20+ seasons while the Ducks assumed Tulsa’s role of a stepping stone?

These are questions that Tulsa players and fans will be left to ponder forever while their program continues to struggle to break into the mainstream, but thanks in part to an old pair of black cleats Oregon’s long-standing Duck-Luck foe had been vanquished, raising the program to heights never before achieved.

“After that bowl game we started getting TV attention, we had almost never been shown on television before that,” Tony Hargain remembered. “The program just started building from there, that bowl game is what changed everything.”

Oregon fans can now dream of very realistic Pac-12 titles and national championship trophies for the foreseeable future, thanks to Robin Cole’s grungy old Super Bowl cleats and the student-athletes who decided to buck the old ways to create their own winning traditions.

Related Articles:

These are articles where the writer left and for some reason did not want his/her name on it any longer or went sideways of our rules–so we assigned it to “staff.” We are grateful to all the writers who contributed to the site through these articles.