Oregon has never been a school to shy away from experimentation over the years. From being one of the first schools to utilize pre-snap motion in the 1940s (known as “Oliver’s Twist,” named after head coach Tex Oliver), to the edge defense in the 90s, and the innovative spread offense the Ducks run today; there has never been a fear to tinker with the game of football.

Keeping in mind Oregon’s ability to be innovative and think outside the box, It should not be surprising that over the past three decades the University of Oregon has had repeated success in taking sought-after track athletes and converting them into quality wide receivers that have excelled in the NFL. Starting with JJ Birden in the 80s, leading into Ronnie Harris and Patrick Johnson in the 90s, and Samie Parker and Jordan Kent in the aughts, the NFL has reaped the benefits of Oregon’s extensive efforts to take pure track athletes over time converting them into wide receivers.

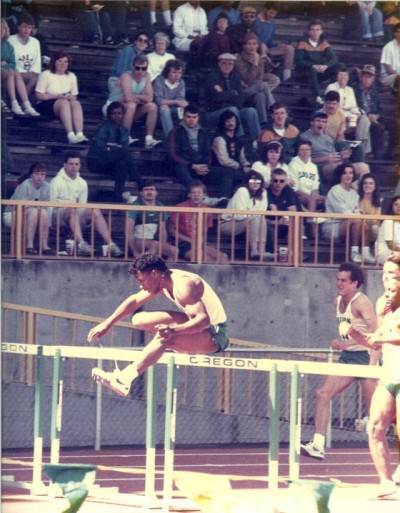

The always popular Hayward Field.

At Tracktown U.S.A., the mecca of running and birthplace of Nike, it seems as likely a place as any to take athletes in one sport and mold them into another. While the overall production of these efforts has been mixed in college, all have gone on to fruitful careers in the NFL.

There’s clearly something to this experiment that the professional ranks find appealing. Is it something in the water or something in the track at Hayward Field? Perhaps it is the Oregon coaching staff, a crew that has been together for decades willing to take a chance on athletes knowing what it takes to be successful? Is it the versatility in skills constantly emphasized by Oregon coaches, or the plyometrics training Coach Jim Radcliffe preaches?

What is it about performing in track & field that compensates for lack of football experience and gives student-athletes a direct path to a professional football career?

For these track stars-turned-football players, all except Jordan Kent had actually played football in high school, but that didn’t necessarily mean that colleges were pursuing them initially for the gridiron.

JJ BIRDEN SETS THE MOLD

J.J. Birden came to Oregon in 1984, an all-state wide receiver at Lakeridge High School in Portland, OR, yet known primarily as a track athlete considered too small to play football.

“The only schools that gave me a chance to try out for football while on a track scholarship were Boise State, Idaho State, and Oregon,” said Birden, now retired after a lengthy NFL career residing in Arizona as a distributor for Xocai Healthy Chocolate. “The track coaches said they would at least ask the football coaches if I could try out, but it didn’t seem like anyone was going to give me a realistic shot.”

Birden immediately began making his mark in track & field, but the thought of also playing football lingered. He would sneak into Autzen Stadium to watch practice, but was never spotted. Birden did participate in intramural football, and dominated. Track and field though remained his passion, his drive, his focus; while football was a lingering pipe dream. Oregon track coaches had indeed reached out to the Oregon football staff, but nothing materialized as far as a tryout.

His sophomore year Birden would finally get noticed, unintentionally so. One day Birden snuck onto the field at Autzen and was hiding behind the goalposts to observe practice. Head Coach Rich Brooks eventually spotted him and walked the full distance of the field towards him, Birden panicking wondering whether or not to run away.

“Coach Brooks approached me and said, ‘Birden, right? I noticed you’ve been watching practice, want to give this a try?’ He said to meet him at his office the next day and we’d talk.”

Birden did arrive at Coach Brooks’ office the next day, and was told that Brooks had spoken with the Oregon track coaches and agreed that they would give him a tryout for a year with the football team. If it didn’t work out, then his scholarship would be switched back to track. Brooks did not guarantee however that if it worked Birden would stick with the football team.

“So I showed up at camp, and I was pretty fearless for a little guy,” Birden remembers. “First two weeks I was 8th or 9th on the depth chart, but after about a week Coach Bob Toledo came up to me and said ‘wow, we never knew you could actually play this position!’ I told them ‘yeah well you guys never gave me a chance.'”

Within a couple weeks of practice JJ Birden had moved up to second string on the depth chart and his future as a two-sport star seemed bright. Coaches worked closely with him to teach Birden the finer details of the wide receiver position, while simultaneously his career flourished on the track. The two sports did overlap somewhat, meaning that Birden only was able to participate in spring ball once during his time at Oregon, though considering his smaller frame perhaps this wasn’t such a bad thing.

“I don’t think any other guys who went out for both football and track after me got away with only participating in spring ball once, I played four years and only had one spring ball. Because I was a small guy though it was good for me to have less wear and tear on my body, even though spring ball would have really helped me contribute more in college.”

Birden not participating in spring ball shows how far Oregon football has come from the 1980s, when track & field was the premiere sport in Eugene. The likelihood of this happening today, a student-athlete on a football scholarship skipping spring football to focus on track, seems absurd.

Birden trained with the coaching staff, worked closely with strength & condition coach Jim Radcliffe to develop his body more to sustain the blows of football, and learned the ropes of how to play wide receiver in the pro-set offense.

However, all the training and preparation did little in terms of production at Oregon, as injuries unfortunately derailed JJ Birden’s production at Oregon. His junior year (1986) he had a real shot to become a consistent contributor and was playing often, but a broken arm suffered in the third week of the season at Nebraska ended Birden’s year.

1987 Birden again suffered a severe injury, a badly sprained ankle suffered vs. UCLA limited his playing time for much of the season, and Birden would finish his career as an Oregon Duck with only one career touchdown catch.

“I didn’t have much of a college football career in all honesty, I trained hard for it but with the injuries it never quite came together. Plus I was more focused on my track career. That’s why I was surprised when I got invited to the NFL combine, I didn’t even know what it was but figured I would give it a try. So I go there, and I’m sitting at a table with Sterling Sharpe, Michael Irvin, Brian Blades, Tim Brown, and all these other superstars, and little ol’ me at the end wondering what I’m doing here,” Birden laughed. “Talk about intimidating…”

“So I ran and I caught passes, but I figured that was it, I was focused on trying to make the Olympic team, I was going to go back to finish up my season in track, but teams started talking to me. I couldn’t believe they were actually interested in drafting me.”

Coach Rich Brooks helped JJ Birden acquire an agent for the NFL draft, but despite the advice to stay in the dorms Birden chose to skip the draft and go to classes, so convinced that there was no way an NFL team would actually draft someone with such little college football game experience.

“I got a call from Marty Schottenheimer of the Cleveland Browns and he said that they just drafted me in the 8th round, I thought it was a prank call. Marty wanted me to come to Cleveland as soon as possible, and I told him I was in the middle of track season and the Olympic trials were coming up. I was doing great that year competing in the long jump and hurdles.”

Oregon’s track coaches gave Birden permission to travel to Cleveland to participate in the mini-camp, but asked that he do nothing so as to avoid injury…at mini-camp, Birden tore his ACL during the third practice.

Birden finished school and decided that the NFL facilities might help him rehab while on the IR for a year still in the hopes of a career in track & field. After stops in Cleveland and Dallas spending two years on NFL rosters without playing in a single game, Birden found himself once again being courted by Marty Schottenheimer, now the coach at Kansas City.

“If I hadn’t been hurt, I don’t think I would have played in the NFL, I had more of a passion for track than I did football. But after rehabbing for two years I felt ready, I ran the fastest 40 time and looked good. I went through training camp with the Chiefs but got cut, but two weeks later somebody got hurt and they brought me back. I wasn’t trying to be the star, just make the team. I was an overachiever, and I learned everybody’s positions so that they could move me around. A couple games into the season some guys got hurt so I got a chance to play, and I had a game with about 180 yards and 2 TDs, it opened a lot of eyes.”

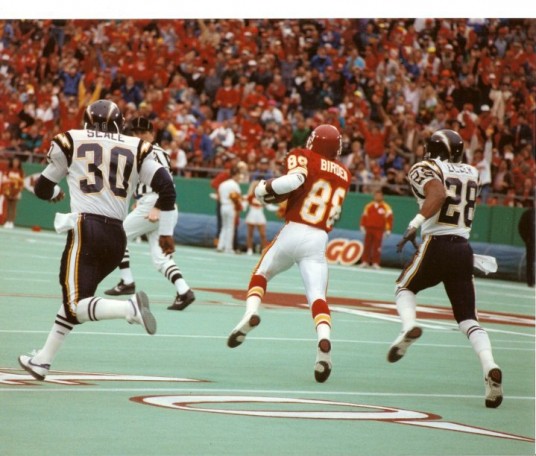

Birden’s NFL career was off and running, one that for the next seven years with the Chiefs and Falcons would make Birden one of the best speedy deep threat wide receivers in the game. Despite his size, the skills and work ethic instilled in him from his time at Oregon with football and track had turned this little guy nobody wanted into one of the top receivers in the pros. Over his career Birden caught 244 passes for 3,441 yards and 17 TDs, including 7 catches over 40 yards while playing with some of the best quarterbacks of the era in Joe Montana, Dave Krieg, and Bobby Hebert.

“I tore up my knee my last year, I could have kept playing but I had spent 9 years in the NFL, which was 9 years longer than I thought I ever would, and I chose to walk away from the game,” said Birden.

“Even though I didn’t play much, I have a lot of fond memories of Oregon. I’m very proud that I was a part of the team in the 80s when things started to turn around, and I worked a lot with guys like Terry Obee and Tony Hargain showing them the ropes…it was kind of funny when Tony (Hargain) and I both ended up playing for the Kansas City Chiefs one year playing side-by-side. I remember one of my first games with the Chiefs I go in for a 4-WR set and I look up and the cornerback covering me is Chris Oldham (Oregon CB 1986-1989). I said, ‘Chris?’ and he said ‘JJ? Is that you?’ Can you believe this is my first game and we’re playing against each other?’ And I remember playing against Anthony Newman and he kept yelling at me the whole game and telling his guys to mess with JJ the whole time…but that was fun, it was great to stay connected with Oregon through the guys that made it to the pros.”

While JJ Birden’s success in the pros was undeniable, the effort put into training him at Oregon had come with little reward for the Ducks. Yet the mold had been set, Birden had proved that coaches could take a raw athlete and convert them into an effective football player, and the Ducks would again find success in converting track athletes to top-level wide receivers.

RONNIE HARRIS PROVES EVERYONE WRONG

One year after J.J. Birden’s unlikely departure for the NFL, another athlete would come to Oregon finding success in both track & field and as a wide receiver, Ronnie Harris.

At Valley Christian High School in San Jose, CA, Ronnie Harris was an accomplished multi-sport athlete despite not looking the part at first glance.

“I didn’t look like a football player,” said Ronnie Harris. “I never played football until I was 15, the coach talked me into playing. I was the kicker for the football team and goalie for the soccer team, played basketball, and ran track. Soccer was my main sport, I was MVP of the varsity soccer team.”

Harris was blessed with incredible foot speed and a long stride, deceptively able to cover a lot of ground for someone of his stature. One day Harris was approached by the football coach and asked what his 40-time was, when Harris responded 4.5, the coach flipped out and demanded he play football.

“He taught me the game, he’d put me outside and say, ‘now just run as fast as you can down the field and we’ll throw you the ball.”

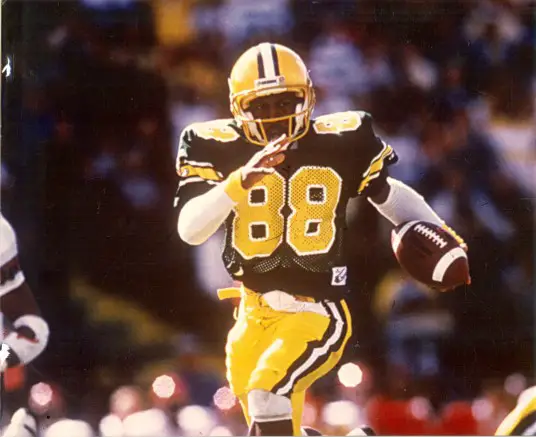

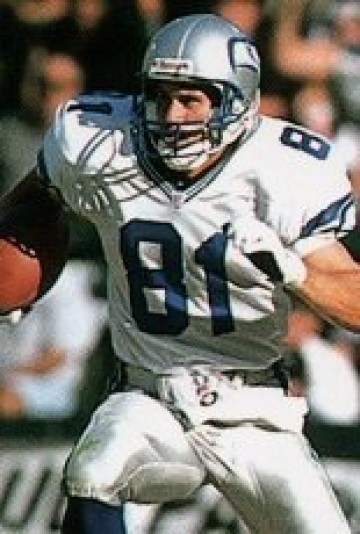

Ronnie Harris played seven years in the NFL with the Patriots, Seahawks, and Falcons

Harris was recruited heavily by Washington, but they canceled his recruiting trip to the UW campus at the last minute because they were closely recruiting another player at the same position, so instead Harris chose to visit Oregon and ended up signing a letter of intent to play football with the Ducks.

“I chose Oregon because of Eugene and the family atmosphere, a college town that rallies around its school, everything it offered in 1988 was really cool to me. I came to Oregon to play football, track was just a bonus. I ran against a lot of athletes in high school in California. I had a good track career, but I didn’t think it would be the main deal for me. I came into Oregon hurt, on crutches because of a hyper-extended knee, and then right before spring ball freshman year I pulled my hamstring, but still ran a 4.3. I hadn’t really talked to anyone about track as I was there with a football scholarship, and I was barely getting by in that as the 6th or 7th wide receiver.”

A phone call from Oregon decathlete Mohammed Oliver would change Harris’ planned football-only career at Oregon. Some athletes on the Oregon track team had been injured, and Oliver asked Harris to run in a meet vs. Nebraska, Harris agreed.

“It was so much fun, I decided that I wanted to do both football and track,” said Harris.

His first couple seasons at Oregon Harris played football sporadically, often injured and still learning how to play wide receiver, working with the coaches to learn the finer details of football. Harris received a blessing from Head Coach Rich Brooks to join the track team full time. Harris spent many hours with Coach Radcliffe fielding punts in Autzen Stadium and running routes, while improving his running technique with Track Coach George Walcott.

“I remember in high school I had an opposing coach tell me that I was the fastest guy he had ever seen that can’t run. I was fast in spite of myself. Over time once I started running track I was able to improve my body mechanics, become a more proficient runner, learn how to improve my momentum. It really helped in football immensely. The first couple years in football were tough on me because I was hurt and not playing much, and I took it so seriously. The dynamics of football vs. track are so different though, it’s a team effort but you’re also out there alone as an individual. I tried to adjust pressure on myself, and running track taught me to relax, and I was able to apply that to football. It made me a better football player.”

Junior year at Oregon Harris’ training efforts in both sports would finally pay off, with veteran wide receivers and sprinters graduating suddenly opening up opportunities for Harris to shine in both sports.

“Early on I was playing hurt a lot and it would set me back, I’d get moved down the depth chart. You only get so many opportunities, and it comes down to what happens in a particular given opportunity, do you maximize on your chance?”

Harris did just that, becoming a go-to wide receiver and runner for the track team on the 4×100 team. Harris, not looking the part of a typical wide receiver, would repeatedly torch cornerbacks for long plays over-the-top on deep slants and posts for 40+ yard touchdowns with his long stride beating guys deep.

“I’m a white, skinny guy with a long stride, so yeah nobody gave me much respect. I didn’t have the big physique, I looked like a regular dude. But once I started doing really well in football, other guys started going out for the track team too, seeing if they could also improve their speed and technique.”

Senior year in 1992 Harris became the Ducks primary punt returner after an injury opened up a spot, and Harris took full advantage. As both a wide receiver and punt returner, the deceptively fast Ronnie Harris became the primary deep threat for Oregon.

Following his senior year, Harris signed a free agent deal with the New England Patriots.

“My track experience was 51% of why I was in the NFL. At that level they still look at how they can take a raw talent guy and make them better.”

“Teams took a chance and tried to develop me. I had to prove myself every year to make the team as a receiver even though my whole career I didn’t play much receiver, I had to do other things like cover kicks and punts. You have to be sustainable, I learned to become a better receiver in the NFL knowing that I needed to do more than that to stay.”

The versatility and training paid off, as a seven year career in the NFL was to follow with the New England Patriots, Seattle Seahawks, and Atlanta Falcons until retiring in 1999.

Just like in high school and college, Harris didn’t fit the part, but through hard work, raw talent, and training he proved the doubters wrong.

PATRICK JOHNSON BECOMES OREGON’S ELITE DEEP THREAT

With Birden and Harris both in the NFL, in the mid-90s another two-sport star would arrive on campus to continue the trend, lifting Oregon to unprecedented levels.

Patrick Johnson was one of the fastest players in Oregon Ducks history

For Patrick Johnson, athletics wasn’t immediately his goal. He didn’t start running track at Redlands High School in California until his junior year, and finished 4th place in finals at the state meet. His senior year he went out for the football team, becoming a running back. Blossoming into a track star, Patrick became the California State Track Champion in both the 100m and 200m his senior season. Still learning the game of football though, a chance encounter would set Patrick’s course to Oregon.

“Coach Don Pellum is from a place about 20 minutes away from Redlands, so he was in town visiting his mom and randomly came to a game and saw me play. He clearly liked what he saw, because Oregon started recruiting me from there,” Patrick Johnson recalled.

“A couple other schools had recruited me to play defense, Oregon was the only program that wanted me to play offense. I met with John Gillespie (assistant coach under track coach Bill Dillinger) on my visit to Oregon and I asked about running track. They were iffy on it, said we’d talk about it when I got into school. I signed a football scholarship, and then my senior year of high school I got a lot better at track, won the state championship and all of a sudden (John) Gillespie started calling me a lot asking if I was going to run track. I arrived in 1994 knowing I was going to go out for the track team, but I never had the track mentality, I am a football person first who happened to be able to run really fast, but I had only played one year so I still had to learn how to play the game.”

Johnson became an accomplished runner for the Oregon track team, but playing time early at wide receiver was tough to come by, buried beneath veteran wide receivers during Oregon’s remarkable run to the Rose Bowl in the 1994 season.

He defeated legendary track star Carl Lewis in a 100m race at the Drake Relays, and won the Pac-10 championship in the 400m as a freshman, becoming one of the top sprinters in the nation. But for all his success on the track, football remained his primary goal.

“John Ramsey (now quarterbacks coach with the San Diego Chargers) was my receivers coach my freshman year, and then Chris Peterson (now Boise State head coach) was my position coach the rest of the way. They helped me so much in just learning how to play the game. They taught me so much, I had to learn how to catch the ball and I’d spend hours catching passes from them and working on running routes, it took a long time for me. It all really didn’t click until my senior year in 1997.”

Through repetition Patrick Johnson slowly acclimated to college football. Speed wasn’t his problem, any time he stepped on the track or the turf he was the fastest man out there, but learning the fundamentals of football was a different matter.

Just like with Birden and Harris before him, coaches went above and beyond to teach him the finer points of the game and make him as versatile as possible. Johnson learned every wide receiver position; slot, flanker, split end, and how to return kickoffs and punts.

The stability in the coaching staff year-to-year made it possible to work with Patrick on a long-term plan to learn the position and grow as an athlete, while his time on the track team improved his foot speed and body mechanics.

By the time his senior year came around in 1997, Patrick Johnson was one of the deadliest weapons in the Pac-10. Being able to play multiple positions and the best return man in the conference, nearly every game Johnson was able to beat opponents deep for long pass completions, matched with two quarterbacks in Akili Smith and Jason Maas with cannons for arms unafraid to just chuck it deep and let Johnson run after it.

During that 1997 season Johnson made one of the greatest touchdown catches in Ducks history in Oregon’s improbable 1997 comeback victory over Washington in Husky Stadium.

Following his senior year, Patrick Johnson was selected in the 2nd round of the 1998 NFL draft by the Baltimore Ravens. He played 8 years in the NFL and CFL, winning a Super Bowl with the Ravens. After a lengthy career with the Ravens, Redskins, Jaguars, and Toronto Argonauts, he retired following the 2007 football season.

Patrick Johnson played professional football for 8 years, and earned a Super Bowl Ring with the Baltimore Ravens.

“The more I knew about being able to play multiple positions on the field, the longer I was able to stay in the league. If you only do one thing, you won’t last. When I got to the NFL there was no learning curve because I knew all the concepts already because of the coaches I had at Oregon, they made my career.”

THE TREND CONTINUES…

The grand experiment of JJ Birden had turned into solid production with Ronnie Harris and the creation of the ultimate deep threat in Patrick Johnson. The mold was set, the project proven. Oregon was a team now defined by speed, and the coaching staff would pursue it wherever they could find it in an attempt to capture the magic once more.

They would repeat this success twice more to date, with Samie Parker and Jordan Kent.

Parker was a star track and baseball athlete in Long Beach, CA, when he was recruited to come to Oregon in 1999. Much like with Ronnie Harris, initially Samie Parker focused only on football, but like the others there were a lot of growing pains learning the position. As a kick returner and deep threat his skills slowly began emerging, right around the same time he joined the track team in 2000.

Oregon wide receiver Samie Parker wore #1, appropriate for the #1 receiver for the Ducks in career receptions and yards

Parker’s career at Oregon would end quite prolifically, with his final game as a Duck in 2003 being one for the ages with 16 catches against Minnesota in the Sun Bowl. The Ducks would lose that day, but Parker became the all-time and single-game receptions leader and all-time yardage leader at Oregon while also setting multiple Sun Bowl records.

His most iconic moment exemplified Oregon’s success in transforming track athletes into wide receivers, catching an 80 yard touchdown pass in the 2001 Fiesta Bowl from Joey Harrington, the signature moment in one of the best seasons in Oregon Ducks history.

Parker’s career at Hayward Field was also fruitful. He finished 4th in the 60m at the 2002 NCAA Indoor Championships and was named an All-American. 2003 he would repeat this feat, as All-American Samie Parker finished 5th in the 100m NCAA Championships and 3rd in the 60m NCAA Indoor Championships.

NFL teams drooled over yet another speedy Oregon wide receiver/track star, and Samie Parker was drafted by the Kansas City Chiefs in the 4th round. Parker played four seasons with the Chiefs, followed by time with the Oakland Raiders in 2009, and has continued his professional football career playing in the arena football league and currently in the UFL with the Las Vegas Locomotives (alongside fellow Oregon wide receiver Cameron Colvin).

Samie Parker played for the Chiefs and Raiders in the NFL, and continues his professional career currently with the Las Vegas Locomotives of the UFL

After Parker, it seemed expected that any time a natural track athlete came to Oregon they would try out for football. Numerous track athletes participated in football as walk-ons, and many football players were now running on the track team, the symbiotic relationship between the two sports now clearly defined as being mutually beneficial.

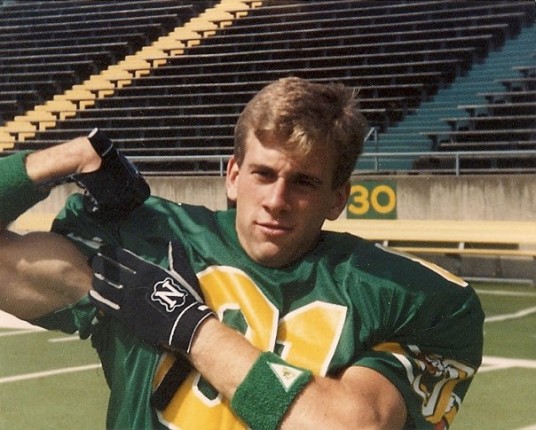

Jordan Kent had not played organized football at any level, a local product from Churchill High School and son of Oregon men’s basketball coach Ernie Kent. Yet after two years of playing basketball and running track for the Ducks, the constant nudging of Oregon coaches to try out for football convinced him to do so. He had never even put on a football uniform before prior to 2005 when he became one of only a handful of athletes to letter in three sports at Oregon, the first since World War II, and the first in the Pac-10 since 1970.

In 2005 Jordan Kent became the first Oregon Ducks athlete to letter in three sports since World War II

Like had been done before with his predecessors, coaches worked with him extensively teaching him the fundamentals of football. Recognizing his pure athletic abilities, they trained him on how to run a route tree, how to catch, how to block, how to take his track and basketball abilities and apply them to the game of football.

By mid-season 2005 Kent was ready, and against Washington State the third catch of his career would be a long touchdown that proved key in Oregon’s narrow victory over the Cougars in Pullman, WA.

Kent’s contributions during the 2005 season were minimal, but his speed and athleticism shined when he was on the field. 2006 he dedicated his efforts to football, choosing to not participate in basketball.

His senior year in 2006 Kent finished 2nd on the team in receptions and was a lethal deep threat, going from raw athlete to talented veteran receiver.

Jordan Kent had never played organized football prior to his junior year of college, but became a viable weapon for the Ducks

On the track Kent was a four-time All-American, anchoring the 4×100 relay team and 4x400m relay, and as a runner in the 200m. His relay team finished 3rd in the 4×400 and 6th in the 4×100 at the 2005 NCAA Championships and Kent was named an All-American. 2006 the team would return, becoming Pac-10 champions in the 4x100m relay, and finishing 7th in the 4×100 and 6th in the 4×400 at the 2006 NCAA Championships.

Once again the NFL immediately took notice. At this point based on the success of Birden, Harris, Johnson, and Parker it was expected that any track athlete Oregon converted into a wide receiver would make it in the NFL. The Seattle Seahawks drafted Kent in the 6th round of the 2007 draft, and he played several years with the Seahawks and Rams.

Now whenever Oregon’s football recruiting classes are announced it is an expectation that many of the wide receivers, running backs, and cornerbacks will also compete in track & field for the Ducks. Track athletes in turn are occasionally nudged to perhaps give football a try as well. Oregon coaches encourage the overlap to refine their athletic skills. The NFL has taken notice, with more Oregon athletes entering the professional ranks than ever before, the tradition established by Birden, Harris, Johnson, Parker, and Kent will continue for the foreseeable future.

-After retiring from the NFL J.J. Birden invested in several successful businesses. He lives in Arizona and is a distributor for Xocai Healthy Chocolate, http://www.jjbirden.com.

-Ronnie Harris is a youth pastor in Bothell, WA, who remains close to the Oregon Ducks traveling to games often with his family.

-Patrick Johnson is retired from the NFL and living in Dallas, TX, the VP of Investor Relations at 1st Resource Group.

-Samie Parker continues to pursue professional football, currently playing in the UFL with the Las Vegas Locomotives alongside fellow former Oregon Ducks wide receiver Cameron Colvin.

-Jordan Kent continues to pursue track aspirations while working as a trainer with Edge Combines, and co-hosts ‘Talkin’ Ducks’ on Comcast Sports Net.

Related Articles:

These are articles where the writer left and for some reason did not want his/her name on it any longer or went sideways of our rules–so we assigned it to “staff.” We are grateful to all the writers who contributed to the site through these articles.