The Ducks have lost two straight BCS bowl games, including this 22-19 national championship defeat to Auburn last January. Will Wisconsin extend the streak to three?

If you had told me on the morning of January 11, 2011 that I’d ever be ready to forgive Cam Newton, I’d have asked how your straight-jacket is fitting. But just as we sometimes end up learning something cold but truthful about our team sometimes after a devastating loss, so too can going from 0-0 to 1-1 with cancer in a span of weeks give you a whole different perspective – one you never expected.

If I wind the clock backwards, will Oregon get to play the BCS National Championship game over again?

On January 11, 2011, I never made it out of bed. I just stayed there all day and through the evening, writhing under the covers. I never ate a bite all day, and whatever food had been in my stomach was vomited away the night before anyway.

Given the date, Duck fans surely understand the reason for all this. It was the day after Oregon lost the national championship on the last play of the game. Proud as I may have been by my beloved team’s moment in the championship game, I had felt absolutely devastated by the loss, like a skydiver whose parachute had failed to open.

As if the devastating disappointment of missing the chance to win the national championship weren’t enough, I was also over-dosing on moral self-righteousness. I was absolutely certain we had been wronged. The Ducks hadn’t just lost the national championship game, I reasoned (along with hundreds of thousands of others). They had “lost” to a team who’s star player, quarterback Cam Newton, never should have been playing.

Months later, still fuming over the loss of the BCS National Championship and Cam Newton being allowed to participate, I wrote this article about the injustice of it all.

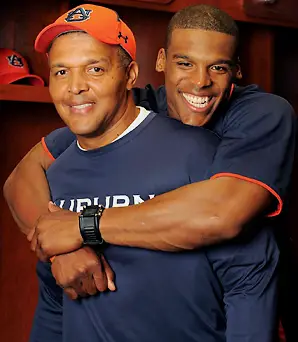

Cam and his dad Cecil, perhaps celebrating the large anonymous donation that led to Cecil’s church being renovated.

Though no smoking gun of evidence ever emerged to convict Newton and his father, Cecil, of a pay-for-play scheme, a Mississippi State assistant coach had gone on record testifying that Cecil Newton had, before Cam signed with Auburn, demanded $180,000 for his son to sign with the Bulldogs.

Former Auburn players also testified that they had received money for playing at Auburn. The NCAA has certainly enacted penalties just on hearsay alone in the past, so why did they so quickly admonish Newton of any wrongdoing?

Then there were the what-ifs of the game itself. What if the referees had called it a fumble when Newton unequivocally fumbled the ball during a sack at the Auburn 19, a sure Oregon touchdown if properly called. What if Oregon had not come up empty handed inside the 5-yard line on four tries? What if Michael Dyer had been correctly called down? What if the field hadn’t been watered down enough to make it ridiculously slippery, something that helped Auburn and hurt the Ducks? Cliff Harris’ interception overturned, lest we forget Auburn scored a touchdown on the next play, so take those points off the board too.

I’m still allowed SOME bitterness over the outcome…right?

It all added up. It seemed karma was out to get Oregon, too many unfair things in the lead-up and during the game to accept it and move on, this loss was going to fester in my gut forever.

Like I said, in those dark days of January 2011 after the BCS National Championship, I had no expectation that I would ever be ready to forgive Cam Newton and to make peace with Oregon’s championship loss, but events beyond our control–much like a poorly refereed game and the circumstances of that day, have a funny way of showing the futility of letting it linger. I thought it was the greatest travesty I would ever encounter in my lifetime, but then a funny thing happened on the way to holding a lifelong bitter grudge…Or, more accurately, something not funny at all happened: two loved ones’ were diagnosed with cancer, and one of them didn’t make it.

Three months ago, on March 15, 2012, my partner of 17 years, Valarie, was diagnosed with breast cancer. As if that news weren’t overwhelming enough, Valarie’s father passed away from his own cancer, within a week of her surgery to attempt to remove the tumors.

Surely everyone has his or her own way of dealing with tragedy. Anger, shock, numbness, fear, desolation, even resolute optimism: any means of coping goes if it works for you. For whatever reason, the first thing I flashed to after getting the news about Valarie having cancer was how emotionally devastated I’d been after the national championship game, not to mention the lifetime of stress and worry I’d accumulated as a passionate Duck fan. I thought of the hundreds of games I’d spent pacing in the basement of my apartment during Oregon games, too nervous to even watch on television. I thought of coming home from scores of games at Autzen Stadium over the years without any voice at all, greeting Valarie with a whispered hello.

The night of her cancer diagnosis, I remember talking by phone to my dad, a 1966 Oregon grad who had started taking me to Duck games when I was in first grade. We’d experienced some of the greatest joys of our lifetimes at Autzen Stadium and in Pasadena. There was the Bill Musgrave-led victory over Washington in 1987 witnessed after seemingly a generation of Husky domination. There were a host of Civil War victories against over-matched Beaver teams throughout the 1980s. There was the Joey Harrington-led triple overtime win against USC in 1999, the Akili Smith and Reuben Droughns domination in early 1998, the Jaiya Figueras sack and fumble recovery for a comeback win against Illinois during the Cotton Bowl year of 1995, and countless other memories that have served as the backdrop to my life.

One of many memories that I’ll always cherish

But on this night, I sobbed into the phone as I confessed to my dad that I suddenly felt absurd, ashamed and stupid for treating Duck games for the past 20 years as life-and-death matters. Now that Valarie was literally clinging to life and her dad was facing death (from an unstoppable pancreatic cancer), the importance of a football team’s fortunes seemed very, very small. And I felt like an utter fool. “I’ll never be the same Duck fan again,” I swore, tears rolling down my cheeks. “I thought it mattered so much, but I’d trade all the Rose Bowl wins and national championships in the world for Valarie and her dad to be okay.”

Within days of Valarie’s cancer diagnosis and the scheduling of her lumpectomy surgery, we had to fly to Pennsylvania to be with her dad. By this time the doctors had sent him home from the hospital, giving up on chemotherapy or other means of cure. It was time for Hank Smith, a salt-of-the-earth auto mechanic who spent more than 30 years working seven-day weeks (his only days off were Christmas, Easter and a few vacation days each year), to come home and pass away, surrounded by his family.

When we arrived, he was still somewhat lucid, welcoming me to their home and accepting the occasional slice of lemon-meringue pie. Within a few days, though, he had made the final descension from life, his beer-belly long since given way to rail-thinness, and consciousness only a fleeting presence. We were there with him all the while, administering morphine and catheters and preparing ourselves to say goodbye.

One night, though, which turned out to be the eve of Hank’s passing, I suddenly turned another chapter in my Ducks fandom. I’d still felt more distant from the team than at any point in my life as I struggled to keep up with this emotionally overwhelming trial. The idea of football, or caring about it so limitlessly, still felt absurd. But as one sits for hours at a patient’s bedside, it’s natural to reach for a TV or laptop for entertainment. Without quite realizing what I was doing, this evening I found myself going to YouTube for a 39-second clip I had bookmarked earlier in the year: De’Anthony Thomas’ 91-yard Rose Bowl touchdown.

Sitting at Hank’s kitchen table that night, as he lay in a makeshift hospital bed in the next room sleeping fitfully, I felt a stream of tears rolling down my cheeks as I replayed the spectacular Thomas run over and over. I came to know the clip so familiarly that I’d lip-sync Brent Musberger’s call: “And exploding into the middle is De’Anthony Thomas. Can’t catch him! Touchdown, Oregon.”

Whereas I’d felt ashamed about the lengths of my Oregon football passion upon first hearing the news of Valarie’s cancer and her father’s grim chances, now those passions were giving me a kind of emotional life-preserver: something joyous to cling to amidst the sinking ships and stormy seas.

After a few months of off-season reflection, I’m still not sure if my hope going forward as a Duck fan is just wishful thinking or a true change. I feel pretty confident that I’ll be able to keep the stresses of a game in check a little more, knowing it’s not life and death no matter what type of high-stakes or feverishly intense game is being played. But it’s hard to break from a lifetime of habit. After all, I’ve spent years as a head-scratcher to even my fellow Duck fans. I get so nervous during Oregon games that I can’t watch them live on TV. I just scrub floors and wash dishes, or walk endlessly through Portland, obsessively checking and re-checking the score. (Somewhat oddly, I’m only able to watch a Ducks game in person. When you can scream with 60,000 others it makes you feel the ability to impact the outcome of the game – and thus longer so helpless.)

Now, though, I’d like to actually try watching a Ducks outing on TV and maybe even possibly enjoy myself. I’d like to keep the same passion that has made me scream and leap into the air over marquee wins and magic moments, but without such a caustic overpowering sense of devastation. Maybe that’s having it both ways, or maybe that’s called being a saner sports fan. Something about the emotional rollercoaster that I have rode with every snap, every play, even when Oregon might be ahead 50-0, now seems somewhat trivial in the greater context. It is after all (gasp), just a game.

What has truly stuck with me, though, is the desire to stop hating. I used to be very good at hating other teams. I’ve spent most of my life despising the Oregon State Beavers in particular at levels that, like a Spinal Tap amplifier, went all the way to 11. I’d also had a kind of jealous, intense dislike-approaching-hatred towards various squads in Boise, Seattle or sometimes Los Angeles.

Then, after the BCS title game, the hating went off the charts. Auburn made me sure I was Bill Bixby about to go full-on Hulk, anger manifested into physical eruption. (That’s not even getting into hating in other sports. Lakers, anyone?)

To spend one’s time hating rival sports teams is a kind of morbid luxury that I no longer have. In that way, I not only should be ready to forgive Cam Newton of whatever sins I self-righteously convicted him of, but maybe even to thank this outrageously talented quarterback.

To finally break from hating is truly a kind of release of its own. I used to think that hating other teams was the essential flip-side of loving the Ducks, something inseparable from the joy. Now, though, I reject that idea. At the risk of cornball cliché, I’m interested in loving the Ducks, but to hate the Beavers or the Auburn Tigers, or any of the so-called other people in life is a waste of precious time and energy, both of which are hourglasses for us all.

The most important thing to me now is that Valarie’s prognosis seems excellent. The doctors are very optimistic, and life is starting to creep back toward normalcy again. After briefly rejecting my own Ducks obsessions, I’ve got tickets for the season opener, and I can’t wait for the game.

Come Civil War time or a bowl game later in the year, sure, I’ll be nervous. Probably really nervous. But no matter how things end, I’m ready to savor the journey of every Ducks football season more than ever, to hear “Mighty Oregon” and look out at a sold-out Autzen Stadium and remember that the only thing better than the Ducks winning is to actually be a Duck.

Whatever you did or didn’t do, Cam, I’d say I forgive you, but I don’t have the right to judge in the first place. Instead, say hi to Jonathan Stewart for me, and someday lets remember the great game that we, the Auburn and Oregon families, collectively shared while the entire sporting world watched.

Related Articles:

Brian Libby is a writer and photographer living in Portland. A life-long Ducks football fanatic who first visited Autzen Stadium at age eight, he is the author of two histories of UO football, “Tales From the Oregon Ducks Sideline” and “The University of Oregon Football Vault.” When not delving into all things Ducks, Brian works as a freelance journalist covering design, film and visual art for publications like The New York Times, Architect, and Dwell, among others.