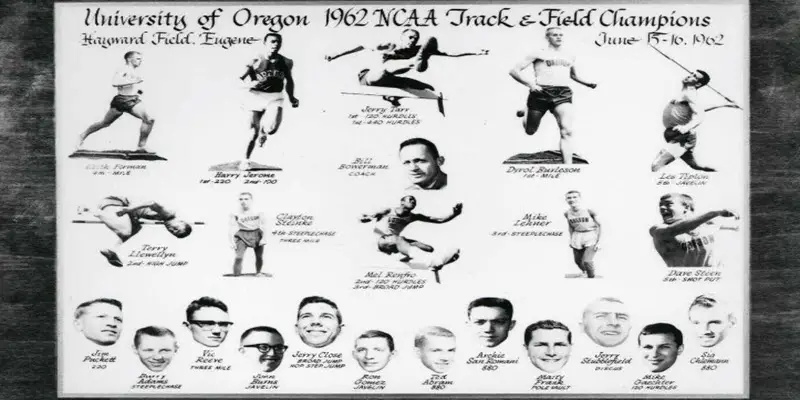

Eugene today is known as Tracktown U.S.A. Nike was founded there, the hallowed track of Hayward Field is like Mecca, necessitating a pilgrimage by the world’s greatest runners to pay homage. Some of the greatest athletes have competed there. Track & Field is synonymous with the University of Oregon, its very identity defined by the glory attained on the historic track.

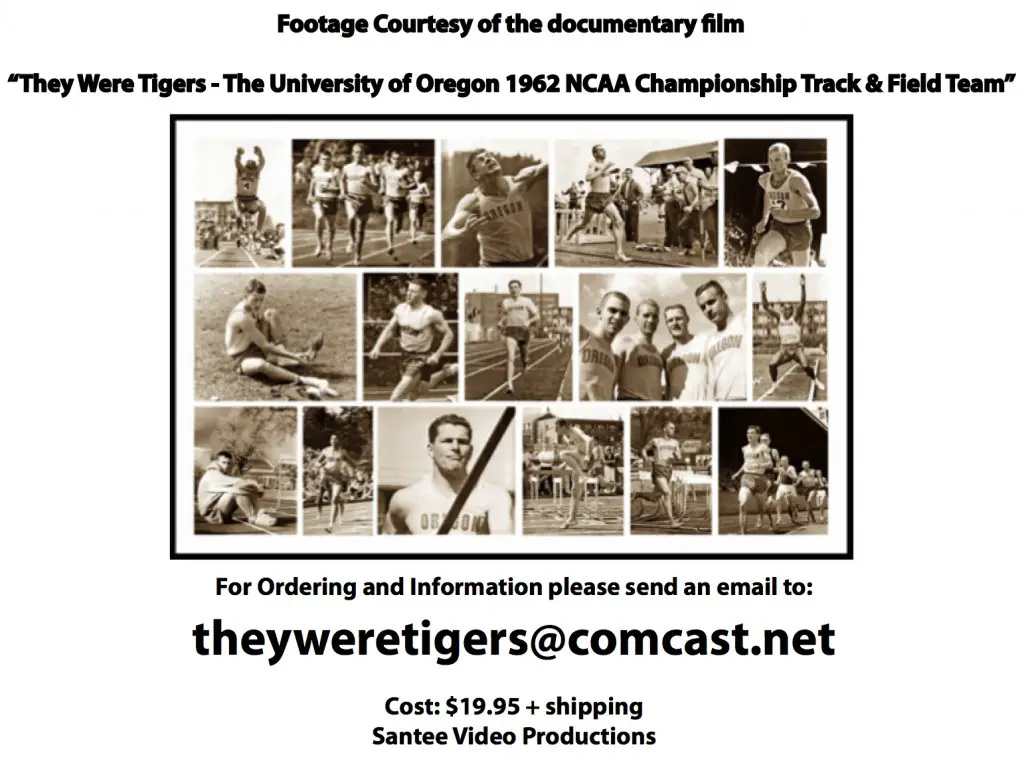

It was 50 years ago that Oregon won its first men’s outdoor track and field championship, the same year that the championships were held at historic Hayward Field for the first time. While Oregon’s place in the sport was established, the Ducks’ dominance was not defined until the year Oregon won it all, the year they became Tigers.

The world of collegiate track and field was very different in 1962. Some of the same track & field events conducted in 1962 are the same as today, but many under different names, as metric system distances weren’t adopted as of yet in the United States except in Olympic years.

Races were measured in yards and miles rather than meters (Olympic years excluding). Decathlons were only held in Olympic years.

Oregon track & field legend Bill Bowerman overseeing his “Tigers”

Some of the events that are still conducted had different names; the triple jump was then the hop-step-jump, and the long jump was called the broad jump. There were also issues with respect to equipment, specifically the pole vault. Prior to 1962 vaulters had been using an aluminum pole, but fiberglass had been recently introduced allowing further heights. There was controversy over whether the new record heights would be recognized. Ultimately, they were.

Not all events contested during the regular season were contested at the NCAA championships. There were no relay races at the NCAA meet. On the other hand, the NCAA championships featured events not regularly conducted during the outdoor season such as the 3-mile race, 3000-meter steeplechase, 440-yard intermediate hurdles and hammer throw.

Unlike the current era of track and field, Oregon competed as a team in a dual meet, triangular meet, or relays every weekend from mid-March to the end of May. The Ducks were involved in 11 meets as a team, with several members of the team participating in other events such as the California Relays during the season.

Nationally, the teams that dominated outdoor track and field were very different from those of 2012. Yes, the Ducks and USC have had outstanding teams in recent years, but there were other strong teams in 1962, most of them on the west coast–San Jose State and Stanford in particular In fact, of the top-ten scoring teams at the 1962 NCAA championships, six of them were from the Pacific Coast states (Oregon, USC, Stanford, San Jose State, California, and Washington State).

Villanova, which finished second to Oregon at the 1962 NCAA Championships, was the only eastern team that was a legitimate track & field power. Surprisingly, there were no major universities from the south, with the exception of LSU, that participated in the 1962 NCAA meet. Perhaps that was in part because of hesitation to compete against African-American athletes, the south still very much segregated at the time.

One other difference in the NCAA meet of 1962 is that athletes from both the University and College Divisions competed in the same championship meet. In addition to athletes from the major universities such as Oregon and USC, there were athletes from such schools as McMurray, Occidental, Texas Southern, Morehouse, and the University of Puget Sound.

Oregon on the Rise

Oregon began its rise as a national track & field power under the legendary coach Bill Bowerman, who some labeled as the “greatest dual meet coach” and having “no equal.” Bowerman, an Oregon native and former Duck athlete himself, assumed the role of head track & field coach in 1948.

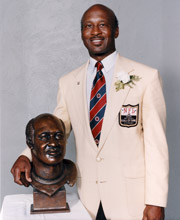

Bill Bowerman is remembered by several of his Tigers, a title he used to refer to the men he coached on the 1962 team, as requiring them to work hard and pay attention to detail. When Mel Renfro, one of three on the team who also participated in the football team (Renfro would go on to a 14-year NFL hall of fame career), was asked to compare his two head coaches at Oregon, Bowerman and Len Casanova, Renfro felt both of them were the same with respect to requiring hard work and attention to detail, but that Casanova probably had more interest in his athletes’ lives outside of sports.

Jerry Tarr, another dual-sport athlete at Oregon and star hurdler who also played in the NFL, recalls that Casanova was probably the more intense of his two coaches. However, that did not prevent Tarr from incurring Bowerman’s wrath one day at practice. Tarr recalls that he and some of his teammates were fooling around with pole vaulting. When Tarr took one vault, he shot up in the air and went sideways, landing outside the pit. Fortunately, Tarr was not injured, but Bowerman lit into Tarr for being “stupid.” Tarr never attempted pole vaulting again.

Even before Bowerman’s association with Phil Knight and Nike, he was attempting to make the uniforms and shoes his teams wore lighter. In 1962, Bowerman (and Oregon) had partnered with Jantzen sportswear to produce lightweight uniforms made from Antron, stipulating that they be 4-ounces or less. This partnership was facilitated by Don Kennedy, a former Duck football player who worked for Jantzen.

As former Oregon broad jump and hop-step-jump competitor Jerry Close told the media, he had to look in the mirror when he put his uniform on to make sure he was wearing something because of how light and form-fitting Bowerman’s uniforms were.

After finishing fourth at the 1960 NCAA meet, and second to USC at the 1961 NCAA Championships; Oregon had set the stage for bigger things. While most track & field experts expected to see USC repeat as national champions, Oregon was going to present a challenge to the developing Trojan dynasty.

Starting Off The 1962 Season Right

Oregon opened the 1962 outdoor track & field season on March 17th, with a dual meet at Fresno State. Oregon would overwhelm Fresno State by a dominating score of 112½ to 17½ .

There were many great performances to open the season.

Archie San Romani, in his first varsity race for Oregon, won the 880-yard race in 1:49.5, which was one of the fastest collegiate times in the country.

Marty Frank won the pole vault at 14′ 8″, which was his then his career-best outdoors.

Terry Llewellyn, despite his diminutive 5′ 8″ stature, won the high jump.

Ted Abram picked up 440 dash title–a race Oregon would win only once more all season.

Other first place finishes included Dave Steen (discus and shot put), Mike Gaechter (another football player) in the 100-yard dash, Jerry Close (broad jump), Harry Jerome (200 yard dash), Mel Renfro (120 yard high hurdles), Bruce Carrington (220 yard low hurdles), Keith Forman (2-mile race), and the team also capture the 1-mile relay.

Next up for Oregon was a triangular meet on March 24th at Berkeley, with California and San Jose State. Oregon won the triangular meet with 81 points to 62 1/3 for San Jose State and 18 2/3 points for California.

Harry Jerome won both the 100-yard dash and 220-yard dash. Dyrol Burleson won the 880-yard run, setting a new Oregon record at 1:48.2. Jerry Tarr won both the 120-yard high hurdles and 220-yard low hurdles, tying the Oregon record held by former Duck football player Jack Morris at 23.3.

This meet was followed by another big Oregon victory as the Ducks dominated the Far West Relays in Corvallis on March 31st, 1962; defeating former Pacific Coast Conference foes Idaho, OSU, Washington, and WSU.

Now 3-0, BYU would be the next victims of Bowerman’s Tigers, losing at Hayward Field in a dual meet 83-48–the first meet held on the newly installed eight-lane track at Hayward. The expansion caused part of the track to run behind the south end bleachers, obscuring the runners from view of the spectators for part of the race.

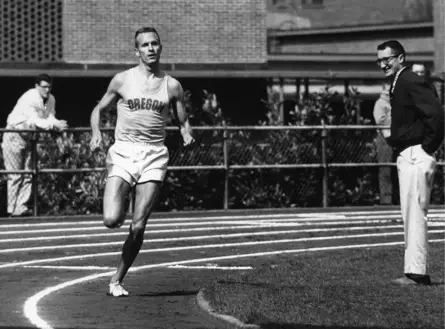

Dyrol Burleson running at Hayward Field in 1962. ©University of Oregon Libraries – Special Collections and University Archives

There were only two events with any significance, the 2-mile race and the 440-yard dash. Dyrol Burleson ran the 2-mile in 8:42.5. This not only was a new Oregon record but a new NCAA record, and the fastest time ever run by an American citizen.

Harry Jerome ran the 220-yard dash and 440-yard dash, winning both events. When asked why he had run the 440 but not the 100-yard dash, Jerome replied that he could not run the 100 every week because it got monotonous. This would be the last time Jerome ran the 440 in 1962, and the last time a Duck would win that event that year.

Oregon remained at home for its April 14th dual meet with Stanford. Again Oregon would prevail, this time with a score of 90 to 41. Sig Ohlemann won the 880 in 1:49.3, then the second fastest time in the country. Oregon now had three of the fastest 880 times in the country by three different runners. Dave Steen (shot put), Jerry Stubblefield (discus), Harry Jerome (100-yard dash), Keith Forman (2-mile), and Jerry Tarr (high hurdles, low hurdles) all brought home 1st place finishes. Once again, Oregon captured the mile relay.

Shocking the Trojans

There was great anticipation for Oregon’s next dual meet. April 21, 1962 was the date for Oregon’s meeting with the defending NCAA champions, the University of Southern California Trojans, set to take place inside the Coliseum.

Coming in, not only had USC won numerous national championships, but hadn’t suffered a loss in 104-consecutive dual meets. It’s interesting to note that while Oregon and USC had both been members of the Pacific Coast Conference for years, they did not compete in a dual meet until 1959, a year after the dissolution of the PCC.

USC had won the first two meetings, however Oregon would win this meet by a score of 75 to 57, ending the Trojans’ winning streak and putting the track world on notice that the Ducks, Bowerman’s Tigers, were the real deal.

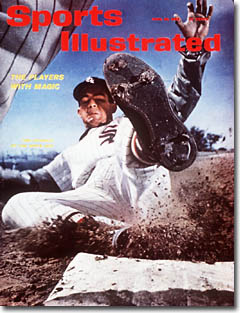

Following the win over USC, Sports Illustrated prominently featured Oregon’s victory in their magazine

Oregon’s victory was led by sophomore Les Tipton, who won the javelin, beating USC’s heavily-favored Jan Sikorsky. On his opening throw Tipton apparently injured his elbow, with the javelin only traveling about 10 feet. That aborted throw drew a response by a typically classy Trojan fan: “Way to go, spastic!” The Register-Guard’s Dick Strite would later label Sikorsky as a “choker,” a comment that would come back to haunt Strite.

Harry Jerome would win both the 100 and 220 sprints, tying the Oregon record in the 220. Jerry Tarr won both hurdle races, setting new meet and field records. Oregon swept the 880, mile, and 2-mile, with Vic Reeve getting the victory in the 2-mile. Jerry Close won the broad jump with a leap of 25″ 1″, setting new meet and personal records.

So stunning was Oregon’s victory over the assumed national champion-to-be USC Trojans, Sports Illustrated ran a prominent feature on the Ducks the following week.

http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1073731/index.htm

Following the meet, Bowerman stated that Oregon still needed to develop talent in the 440-yard hurdles, 3-mile, and hop-step-jump; events that Oregon had not participated in up to that point in the season, but that they would have to deal with if they were to win the NCAA Championships.

USC would return the favor, avenging this loss in 1963, halting the Duck’s unbeaten streak in dual meets at Hayward Field.

Riding High, The Ducks Keep Rolling

Oregon would return to the friendly confines of Hayward Field on April 28th, hosting the Washington State Cougars. Another meet another Oregon victory, dismantling the Cougars 98-45.

Bowerman made a decision to limit his multi-event stars like Jerome and Tarr to single events for this meet. Jerome the the 100-yards, Tarr the high hurdles, and Dave Steen the shot put. Tarr and Steen set or tied meet records.

This would be the first meet of the season in which the hop-step-jump was an event, with Oregon’s Jerry Close finishing second. It was also the first time Oregon ran the 440-yard relay in 1962, fielding a team of Mel Renfro, Jim Puckett, Jerry Tarr, and Harry Jerome. They set new meet and field records.

As a side note, this meet featured a 300-yard dash that was run by Oregon freshmen, Emerald Empire Athletic Association runners, and former Oregon great, Otis Davis. Davis won the race.

The first of two dual meets with Oregon State would take place on May 5th in Eugene, The Ducks once more proving the victors 98-45. Having vanquished USC and rolling over all other competition, the Ducks were proving to be the class of the west, quite possibly of the entire country.

Harry Jerome

Oregon set new meet and field records in the 100-yards, 880-yards, 2-mile, 440-yard relay and shot put. Several other records were disallowed because of the wind (both hurdles and the 220-yards).

The next week, May 12th Oregon had a choice to make. The Ducks already had a scheduled dual meet with the Washington Huskies in Seattle. However, the West Coast Relays were also taking place that weekend in Fresno.

Bowerman made an audacious move, deciding to split his team, sending San Romani, Burleson, Reeve, Forman, Jerome, and Tarr to Fresno. The rest of the team traveled to Seattle. The avowed purpose of sending the top distance runners to Fresno was to break the world record in the 4-mile relay, at that time held by the New Zealand National Team.

Oregon demolished the world mark by an astounding 15 seconds, in a time of 16:o6.9, a single college team overtaking what had previously taken an entire country’s best to achieve. In setting the record, Burleson lapped the anchor man for Western Michigan University, the only other school competing in the race.

Meanwhile, the Ducks were demolishing the hapless Huskies in Seattle 98-45. The Seattle print media was not happy about Bowerman’s insult of sending only a partial Duck team to Seattle. Apparently, they believed the Huskies should be blown out by an even bigger score. The Huskies were truly inept in those days, having only one legitimate star, John Cramer, an outstanding pole vaulter.

Oregon would go on to set meet records in the 880, low hurdles, mile relay, and broad jump. In the absence of Jerome and Tarr, this would be the only 1962 meet in which Oregon lost the 100-yards and high hurdles.

Mel Renfro was in Seattle with the track team, while the Oregon football team was playing its annual spring game with the alumni. Contemporary newspaper accounts say Renfro was excused from spring football practice, which would explain why he was able to compete with the track team every week (and why reports on spring practice do not mention his name). Renfro does not recall it that way, remembering that he was only partially excused from spring practice. Gaechter and Tarr had already completed their football eligibility.

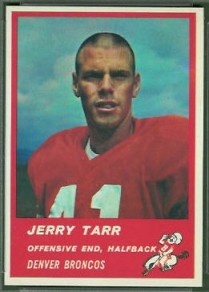

Jerry Tarr

The Far West Championships, essentially a reprise of the Far West Relays, took place on May 19th in Eugene. Oregon would again dominate with a score of 98½ , followed by Oregon State (65 ½), Washington State (39½), Idaho (33½), and Washington (32). Significantly, this meet would feature several new events, including the 440-yard intermediate hurdles, 3-mile, and 3000-meter steeplechase.

Jerry Tarr continued his terrific season, winning both the 120-yard high hurdles and the 440-yard intermediate hurdles, coming 1/10th of a second from capturing the world record in the high hurdles. Terry Llewellyn (high jump), Mike Lehner (steeplechase), Mel Renfro (broad jump), Keith Forman (3-mile), and Dave Steen (shot put) all had 1st place finishes.

Setting More World Records

A week later, Bowerman chose to send some of his Tigers to compete at a meet that had not been on Oregon’s schedule, The California Relays in Modesto, CA (May 26th, 1962). Once again, Oregon’s prominence in track & field was on display, turning heads and setting records.

Harry Jerome won the 100-yard dash in a meet record 9.3 seconds, beating Florida A&M’s Bob Hayes, who had been previously unbeaten. Oregon’s 2-mile relay team of San Romani, Abram, Ohlemann, and Burleson would set an NCAA record. However, they were to be outdone by the 440-yard relay team. Keith Forman would win the mile race in 3:58.3 becoming the third Duck to break the 4-minute barrier. Forman was named the most valuable athlete of the relays.

But not everything went Oregon’s way. Jerry Tarr lost his first high-hurdles race of the season to his nemesis, Hayes Jones. Tarr had taken the lead over Jones midway through the race, but crashed into the seventh hurdle and did not finish. Jones would set a meet record.

As Jerry Tarr recalls, the morning of that race the Oregon team had gone out for breakfast only to be seated in a booth next to Florida A&M’s team, featuring the great Bob Hayes (who would go on to NFL stardom and Olympic titles). Apparently, nothing was said between the teams.

Later in the day, Oregon lined up against teams from Florida A&M, the Los Angeles Striders track club, San Jose State, and Texas Southern (with future NFL player Homer Jones).

Mel Renfro’s recollection is that he had never seen sprinters as fast as those Oregon was matched with. Renfro opened the race for Oregon, handing off to Gaechter for the second leg. At this point, Oregon was trailing the Striders and Texas Southern. Gaechter took off. Unfortunately, he injured his hamstring just before handing the baton to Tarr.

However, Gaechter was able to make the hand-off, and Tarr took off, closing distance on the opponents to one-half stride. With the transfer of the baton to Jerome, Jerome “exploded,” taking the lead within 40-yards and winning by two feet over the Striders’ anchor man.

Oregon had tied the world record for the 440-yard relay, and according to Tarr would have set a new world record if he had not had to wait for Gaechter’s handoff.

Mel Renfro hurdling during National Championships.

The final dual meet of the season was with Oregon State in Corvallis on May 30th, only four days after the California Relays, again Oregon would win, 85-59. While not a particularly memorable meeting, Oregon did set meet and field records in the hurdles, shot put, discus, and mile. Ron Gomez set an Oregon record in the javelin at 244′ 1″. Mel Renfro set a personal best in the broad jump at 24″ 11 3/4″.

Not all went well for Oregon. The 440-yard relay team was disqualified because of a bad hand-off between Renfro and Puckett. The heralded 2-mile race turned out to be a flop as Forman withdrew, explaining he was tired and did not want to be stale for the NCAA’s, and Burleson pulled up because of a muscle cramp. With that the regular season was now over, all that remained was the NCAA Championships on June 15th and 16th, and it just so happened to be Oregon’s lucky year, as Hayward Field for the first time had been picked to host the event.

The NCAA Championships

The NCAA Championships were conducted over a two day period, June 15th and 16th, featuring many great track and field athletes, and a number of athletes who would go on to play professional football. The preliminaries and one final, the 3-mile, were conducted on Friday, June 15th, and the remainder of the finals on Saturday, June 16th.

Friday, June 15th, 1962

The 3-mile run final

The first final was the 3-mile run, the equivalent of today’s 5000-meters. Oregon’s entrants in this event were Clayton Steinke and Vic Reeve, with Keith Forman and Mike Lehner scratched before the race. Steinke was never a serious contender for points in the 3-mile, and dropped out in the ninth lap. However, Reeve had been counted on to score some points, having recorded the second fastest collegiate 2-mile time in 1962. Unfortunately, Reeve suffered two spike wounds to his achilles ligament and had to drop out on the third lap, furious that he couldn’t identify which runner spiked him. The 3-mile was won by Pat Clohessy, the defending champion, of Houston. Brian Turner of Southern Illinois was second, and Dale Storey of Oregon State was third. Pat Traylor of Villanova was fourth.

100-yard dash preliminaries

The preliminaries in the 100-yard dash featured a number of great sprinters, including Oregon’s Harry Jerome, Frank Budd of Villanova (the co-world record holder at 9.2 seconds), Paul Drayton of Villanova, Dennis Johnson of San Jose State, and Roger Sayers (older brother of Gale Sayers) of Nebraska-Omaha. Bob Hayes scratched from the meet, sending a telegram that it was impossible for him to attend–it was assumed Florida A&M could not afford to send him cross-country to the meet.

Budd won his heat in 9.3 seconds, tying the meet record and beating Jerome’s field record. Roger Sayers was second in Budd’s heat. Jerome won his heat in 9.5 seconds beating Dennis Johnson and Paul Drayton. All advanced to the finals.

Shot put preliminaries

USC’s Dallas Long, the world record-holder and defending champion in the shot put, won the preliminaries with a throw of 64′ 7″, a new meet record. Gary Gubner of New York University was second, and future AFL player Billy Joe of Villanova was third. Oregon’s Dave Steen was fifth in the preliminaries at 58′ 3/4″.

880-yard run preliminaries

Oregon’s runners, Archie San Romani and Sig Ohlemann won their quarter-final heats, but San Romani would fail to make it out of the semi-finals, and Ohlemann struggled in the semi-finals. San Romani apparently was suffering from a virus that sapped his energy, and Ohlemann simply did not run well. Ted Abram did not make it out of the quarter-final heats, and Dyrol Burleson was scratched from the event. Jim Dupree of Southern Illinois had the fastest qualifying time.

Dave Steen competes at Hayward Field for the National Championship.

Discus preliminaries

Dave Weill of Stanford had the top preliminary mark, followed by Karl Johnstone of Arizona. The Ducks Jerry Stubblefield and Dave Steen failed to qualify for the finals.

Hop-Step-Jump preliminaries

Preliminaries in the hop-step-jump saw UCLA and future NFL star Kermit Alexander place first with a jump of 50′ 11 1/4″, Washington State’s Eilif Fredericksen was second. Oregon’s only entrant, Jerry Close, failed to qualify. Close was noticeably limping, and explained that he had injured his ankle two weeks earlier and re-injured it on his first jump, the injury keeping him from getting much “lift” on his jumps.

220-yard preliminaries

The preliminaries of the 220-yard dash would go much better for Oregon. Jerome won both his quarter-final and semi-final heats, beating Budd in the semi-finals. Jerome’s times tied the NCAA meet mark and bettered the field record. Budd failed to qualify for the finals. Paul Drayton won his quarter-final and semi-final heats.

Broad Jump preliminaries

The broad jump featured two Ducks, Jerry Close and Mel Renfro, but Close failed to qualify because of his ankle injury. Renfro took second place with an Oregon record jump of 25′ 11 3/4″.

It appeared that Renfro’s leap in the preliminaries would be counted as his best jump for determining his finals placing, but Renfro had one leap of 26′ 8″ that he scratched on. Renfro was irritated that he had scratched on this jump. The preliminaries were won by the defending champion, Anthony Watson of Oklahoma, who complained of the portable broad jump runway, feeling that it had no “spring” and gave the jumper a false sense of security.

120-yard high hurdles preliminaries

Tarr handily won his heat in 13.6 seconds despite having hit the fifth hurdle. The next fasted hurdler was timed at 14.4 seconds. Renfro placed second in his heat at 14.0 seconds, behind Russell Rogers of Maryland-Eastern Shore. Renfro’s time was a personal best despite having hit the seventh and eighth hurdles, he was confident he would not hit the hurdles in the finals.

440-yard dash preliminaries

Next up were the preliminaries in the 440-yard dash, an event Oregon had no participants. Rex Cawley of USC would have the fastest time, with defending champion Adolph Plummer of New Mexico also qualifying for the finals.

Les Tipton about to unleash at the National Championships at Hayward Field.

Javelin preliminaries

Despite complaints that the portable runways used for the javelin were too short, Jerry Dyes, the versatile Abilene-Christian athlete, placed first. Jan Sikorsky, the favorite, placed second. Les Tipton of Oregon placed fourth. Fellow Ducks John Burns and Ron Gomez failed to qualify for the finals.

440-intermediate hurdles preliminaries

Jay Luck of Yale won his semi-final in 51.9 seconds, followed by USC’s Rex Cawley at 52.3 seconds. Tarr won his semi-final in 52.3 seconds, explaining afterwards that he had slowed up. Tarr, viewing Cawley as the chief threat in the finals, was hoping all of Cawley’s other races would tire him out.

The first day of the meet had concluded, with mixed results for Oregon. Certainly, the performances of Jerome, Tarr, and Renfro gave the Ducks hope for Saturday’s finals. However, there was disappointment with Oregon’s failures in the 880 and 3-mile.

Saturday, June 16th, 1962

The Finals

June 16th was a sunny, pleasant late spring day. A crowd of at least 13,000 fans had gathered to view the finals.

First up was the hammer throw, was won by Harvard’s Ed Bailey. Jan Sikorsky would win the javelin finals. Les Tipton failed to improve upon his throw in the preliminaries, and placed fifth. After the javelin concluded, Sikorsky went looking for the Register-Guard’s Dick Strite to confront Strite over his article in which Strite had called Sikorsky a “choker.” Fortunately, Strite was not to be found. Sikorsky was one of the throwers complaining about the javelin runway during the preliminaries, but coincidentally after winning the final, thought it was the best runway he had ever seen.

Broad Jump finals

The broad jump finals were up next. Anthony Watson would place first, winning his second broad jump championship with a jump of 26′ 1/2″. Second place would go to future NFL great Paul Warfield of Ohio State, with a jump of 26′ 0″. Renfro placed third, based on his best jump in the preliminary, after fouling on all of his jumps over 26″0″.

Terry Llewellyn climbs the high jump for Oregon.

Renfro credits weight loss and Bowerman’s coaching for his success in the broad jump. Following the final, Watson had more to say. Like Sikorsky he had changed his mind about the runway, believing it to be the best runway he had ever seen. While Watson had heard of Warfield, he claimed to have never heard of Renfro. When comparing Renfro and Warfield, Watson explained that Renfro scared him because of Renfro’s speed, and that Warfield, while not as fast as Renfro, could get great height on his jumps.

High Jump finals

California’s Roger Johnson won the event, beating defending champion and world record-holder John Thomas of Boston University. Oregon’s Terry Llewellyn would tie with several jumpers for second place at 6′ 9″. This was unexpected as Llewellyn was competing against jumpers who had gone higher than Llewellyn, including two jumpers who had gone over 7′ 0″.

1-mile run final

Oregon got its first championship in this event, with Dyrol Burleson winning in a time of 3:59.8, a new meet record. Oregon’s Keith Forman managed a fourth place finish, explaining later that he was spent by the final lap.

Shot Put final

The shot put would be won by USC’s Dallas Long, while Dave Steen improved his distance from the preliminary but could not move up from his fifth place finish.

440-yard dash

The 440-yard dash was won by Hubert Brown of Morgan State.

Pole Vault final

Oregon’s Marty Frank failed to place in the pole vault, with a height of 14′ 9″. All the top finishers had vaulted at least 15′ 3″.

100-yard dash final

Harry Jerome would next get his chance to beat Frank Budd, the defending champion and co-world record holder, in the 100-yard dash. Unfortunately, Budd prevailed with Jerome finishing second, defeating Jerome by .01 seconds in a time of 9.20. According to Jerome, Budd had simply gotten off to a fast start the Jerome could not overcome.

120-yard high hurdles final

Jerry Tarr would take first place in the high hurdles in 13.5 seconds. However, Mel Renfro had been leading the race at the half-way point and might have won, had he not hit the final hurdle. Renfro would finish second in a time of 13.8 seconds.

880-yard finals

The race would be won by Jim DuPree of Southern Illinois. Sig Ohleman was Oregon’s only entrant in the finals. Ohlemann would be third in the race after the first quarter, but was bumped by DuPree on the final lap and finished last.

Discus finals

No Ducks were in the finals of the discus, which was won by Stanford’s Dave Weill.

220-yard dash finals

Seeking redemption from his .01 loss in the earlier finals, Jerome would get his opportunity for a championship in the finals of the 220-yard dash. Jerome won the race in a time of 20.8 seconds, nipping Villanova’s Paul Drayton at the tape.

Hop-step-jump finals

UCLA’s Kermit Alexander would win the hop-step-jump.

440-yard intermediate hurdles finals

Oregon’s Jerry Tarr would win the race going away, setting a new meet record of 50.3 seconds, thanks to a suggestion from Coach Bowerman about mapping out when to kick, taking advantage of Hayward Field’s architecture to avoid the wind down the stretch.

Steeplechase finals

The final event of the 1962 NCAA Championships was the 3000-meter steeplechase. Oregon was well in the lead for the national championship at this point, but This was Oregon’s chance to put the championship away. There were four Ducks entered; Keith Forman, Barry Adams, Clayton Steinke, and Mike Lehner.

Adams and Forman would fail to finish the race. However, Lehner and Steinke would place third and fourth respectively. The race was won by Pat Traynor of Villanova, followed by Jeff Fishback of San Jose State. With the finishes by Lehner and Steinke, Oregon’s first national championship was complete.

Oregon Ducks, Now National Champions, Compete in AAU Events

Oregon had won its first NCAA Championship with a score of 85 points. While Oregon would win Championships in 1964, 1965, and 1970, it would not score this many points to do so. It was not until 1984 that Oregon scored more points (113) in the team title.

Harry Jerome, Dyrol Burleson, Jerry Tarr, Mel Renfro, Mike Lehner, Keith Forman, Clayton Steinke, Dave Steen, and Les Tipton were all named All-Americans based on their efforts at the Championships–nine from a single school.

There were certainly questions following the meet, such as why had Dyrol Burleson only competed in the mile given his success at other distances. Both Tarr and Renfro believe that it was Bowerman’s decision to limit Burleson to the mile to ensure that he would complete his career at Oregon as an undefeated champion.

However, the NCAA Championships would be Burleson’s last meet for Oregon. Following the meet, Burleson announced that he planned to take the summer off and would not be competing at The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) meet the following week, or the United States vs. Poland and United States vs. Russia meets in July. This decision brought down the wrath of some in the media, accusing Burleson of being unpatriotic.

Burleson relented and entered the AAU meet in the 3-mile. That was not enough to satisfy some, including former Oregon runner Jim Grelle, who accused Burleson of not competing in the mile because Burleson was afraid of losing to Jim Beatty. The 3-mile race did not go well for Burleson, he dropped out after seven laps, the first time he had lost a championship race.

Dyrol Burleson

Mel Renfro was not subjected to such criticism for choosing to not compete in the AAU meet, he was engaged with plans to get married in July.

However, several ducks did participate in the AAU meet. Jerry Tarr won both the high and low hurdles. In winning the high hurdles, Tarr finally beat his nemesis Hayes Jones, the first race Jones had lost since 1960. For Tarr, his victory over Jones was a “big thing,” doing so on the final hurdle. Tarr was less enthusiastic about winning the low hurdles, which he did not feel like running.

Harry Jerome lost to Bob Hayes in the 100-yards, and decided to not run the 220-yard dash. Frank Budd tore a muscle and failed to finish the 100. This would be the only time the three premier sprinters in the world would ever run against each other.

Archie San Romani still had not recovered from a virus, but managed a second place finish in his 880-yard heat. However, he would finish no better than eighth in the mile. Sig Ohlemann reached the finals of the 880 with a career best of 1:48.7. Unfortunately, he would only place eighth in the finals.

Mike Lehner dropped out of the 6-mile race on the 13th lap. Lehner would not fare much better in the steeplechase, missing out on sixth place. Clayton Steinke place even further back. However, Keith Forman managed to finish second in the steeplechase despite not having run the event since high school.

Forman would go on to finish third in the steeplechase in the meet against Poland, and third in the 1500-meters in the meet against the Soviet Union.

Tarr would win the 110-meter hurdles against the Soviets, beating Hayes Jones for the second time.

Track & Field, or Professional Football?

With the conclusion of the United States vs. Union of Soviet Socialist Republics track meet, Tarr had some decisions to make about his future.

Tarr had been a two-sport star at Bakersfield Junior College before coming to Oregon. He was being recruited by USC, but USC wanted Tarr to decide between playing football and competing in track. Tarr wanted to play both sports. His coach at Bakersfield put Tarr in contact with Jerry Frei, the Oregon’s line coach, and Tarr decided to come to Oregon.

His first season at Oregon (1960), Tarr played right end on offense and defensive end. He got several starts. His second season at Oregon was marred by the death of his father, which caused him to miss practice time and games, causing Tarr to fall down the depth chart.

Bowerman clearly did not want Tarr to turn to pro football, believing that by the 1964 Olympics Tarr would be the best hurdler in the world. That generated speculation that Tarr would join the military, where he would be in “special services” and permitted to continue his track career.

However, then stories started circulating that Tarr had been spotted at the Denver Broncos training camp, and had been offered a $10,000 contract–these stories turned out to be true.

Tarr signed with the Broncos, ending his track career. He explains that he needed to get out in the world and earn a living, and playing pro football would be one way to do that. Tarr’s career with the Broncos lasted only one season despite some very respectable statistics. However several concussions

When asked why his pro career last only one season, Tarr explains that over time he had suffered a number of concussions. After suffering more concussions with the Broncos, Tarr decided to give up football, explaining that he lost his nerve.

Perhaps the better explanation is that he realized that the concussions were having a long-term impact, and it would be better for his long-term health to retire from the game. While his NFL career was short, Tarr has no regrets about having given up his track career to play football.

With the graduation of Burleson and Tarr, and Harry Jerome not competing for the Ducks in 1963, Oregon placed third at the 1963 NCAA Championships. 1963 was not a good year for Mel Renfro on the track, while he continued to compete in the broad jump and hurdles he did so with less success than in 1962. Perhaps it was his sore left knee that hindered Renfro in 1963, as he failed to qualify for the finals in his events in 1963.

On the football field however Renfro shined. As the starting halfback for the Ducks, Renfro led the way to Len Casanova’s only bowl-winning team as an Oregon coach and best single-season victory mark, culminating in a Sun Bowl win over SMU. Renfro turned heads on both sides of the ball. Once again, the NFL came calling for one of Bowerman’s best.

Renfro was drafted by the Dallas Cowboys, but could have still competed for Bowerman’s team in 1964, but once he signed a contract with Dallas it negated his eligibility, Renfro had turned pro. Renfro, of course, would not regret that decision, a 14-year NFL career (including 10 pro bowl selections) and election into the NFL Hall of Fame as one of the greatest players in professional football history.

Jerome would return in 1964 to win the 100-meters at the 1964 NCAA Championships, and Les Tipton won the javelin, helping lead Oregon to its second team national title, accumulating 70 points. It was good enough to be the best in the nation, but the total wouldn’t come close to matching the performance displayed by Bowerman’s Tigers during Oregon’s first national championship.

Bill Bowerman’s Tigers certainly roared in 1962, winning every meet they participated in, setting or tying numerous records, including two world records, and setting the stage for future championships.

Kurt Liedtke

Klamath Falls, Oregon

*Special thank you to Jerry Tarr and Mel Renfro for providing interviews for this article, and to Jeff Eberhart of the University of Oregon for facilitating the opportunities to speak with Mr. Tarr and Mr. Renfro.

Related Articles:

These are articles where the writer left and for some reason did not want his/her name on it any longer or went sideways of our rules–so we assigned it to “staff.” We are grateful to all the writers who contributed to the site through these articles.