As programs look to fill their rosters with new recruits, every year inevitably teams ponder whether or not to consider adding transfers to their ranks. Some come from junior colleges, some from other schools. Sometimes it is due to academics, or disciplinary reasons, or the opportunity for playing time that makes student-athletes pursue alternate choices in their education and football careers.

Whatever the reasoning for the athlete, it is a risky proposition for the program to take on a transfer player. Some may come with a stigma, either spotty academics or disciplinary problems or ego or a wealth of reasons for why they may have washed out at their previous school. For junior college recruits, it is expected that the first season will be largely just adjusting to the speed of the game at the FBS level, it is common practice for JC’s to redshirt if they have one available to spend a year adjusting to the speed of the game. JC’s are thought of mostly as stop-gap measures, a hole in the depth chart necessitating a body to fill for what is hoped to be one solid year of contribution.

Still, transfers have to prove their merit on the team perhaps more than recruits fresh from the prep ranks, having had prior college experience there is added expectation, whether fair or not, that they will be able to acclimate and contribute.

Oregon has had its share of transfers that have panned out well. Former players like Jeremy Gibbs, James Finley, Fenuki Tu’Pou, Palauni Ma’Sun, Pat So’oalo all provided two solid years, while others after their year of learning curve gave one very solid season to the Ducks (Matt Harper and Terence Scott in recent years). But for every success, there are tales of washouts, headcases, and injuries derailing the opportunity transfer players have to make their mark.

Thanks to the recruiting efforts and recent successes on the field, Oregon does not recruit junior college players nor pursue potential transfers nearly as often as they once did. But for a time the Ducks were nicknamed “Second-chance U,” a place where guys could come to redeem themselves for past mistakes. For others who were under-recruited or looking for that opportunity to shine, Oregon became a destination to prove your merits, a place where the chip on that shoulder could be utilized for maximum effort.

It is in this context that for a stretch of 10 years, Oregon consistently found great fortune through transfer running backs coming to the Ducks to become the battering rams in Oregon’s potent offense. From 1993 – 2002, only one season (1995) did the Ducks not have a transfer running back leading the charge through the Pac-10.

The era of the transfer running back being king at Oregon started in 1993, when Dino Philyaw’s long winding cross-country path led him from rural North Carolina to Eugene, OR.

_____________________________________________________________________

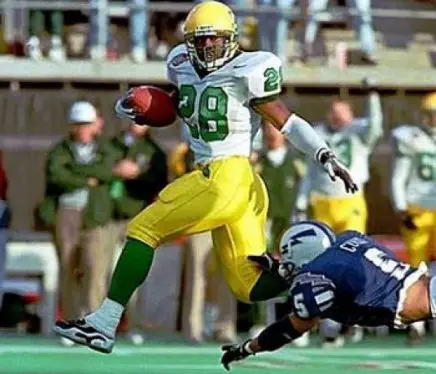

DINO PHILYAW (1993 – 1994)

5’10” 210

Dudley, NC (Southern Wayne High School)

Taft Junior College transfer (Taft, CA)

Dino Philyaw had been one of the top high school running backs in North Carolina, he originally signed a scholarship with Maryland, but not having yet passed the SAT he chose instead to play minor league baseball with the Cleveland Indians when the opportunity arose.

“After baseball didn’t work out, I looked at going to junior college to get back into football,” Dino Philyaw remembers, now retired from football and running his own catering service in the Eugene, OR area. “Taft junior college (Taft, CA) recruited the east coast heavily, there were a lot of guys from back home that came out to play at Taft. I had the opportunity to as well, so I jumped on a Greyhound Bus and rode it cross-country to California.”

After a stellar first year at Taft, Philyaw was declared a preseason All-American in the JC ranks, but an illness limited his playing time his sophomore year. Hoping for a shot at division-1 football, Philyaw sent his highlight film to Oregon, which drew the attention of offensive coordinator Mike Bellotti and running backs coach Gary Campbell.

“I watched the 1992 Independence Bowl when Oregon played against Wake Forest, and I had originally commit to Wake. But I liked what I saw from Oregon, I saw their roster and thought that was the place I needed to be to get to the next level,” said Philyaw.

“I was looking at other schools, at one point I had a flight to Hawaii or last minute a chance to go on a recruiting trip to Oregon, I chose Oregon. I loved the community, the coaches, the team, it just felt right,” Philyaw recalls.

Coming to play at Oregon in 1993, Philyaw had big expectations for the team. He told head coach Rich Brooks that he had come to Eugene to lead the Ducks to the Pac-10 title and the Rose Bowl, coach may have patronized him at the time but Philyaw’s prophecy would become all too true.

1993 Oregon had a senior running back workhorse named Sean Burwell, who would finish 5th on the all-time rushing yards list at Oregon after four solid years of contributions. Philyaw saw the field as a back-up, but he had difficulty acclimating to the new playbook and speed of the game. It would be the 1994 season, his senior year, when Philyaw would make his iconic marks on the history of Oregon football.

The 1994 Oregon Ducks football season is remembered for many reasons, but often forgotten is the slow start to the season. Philyaw was the primary backup to Ricky Whittle, but a month into the season Oregon was 2-2 heading into Los Angeles to play #5 USC at the Coliseum. Whittle was hurt, along with starting QB Danny O’Neil and All-American CB Herman O’Berry, meaning many of the youngsters would get their first consistent playing time. Most anticipated a bloodbath, what happened instead propelled Oregon towards the Rose Bowl and the rise to national prominence.

“I always felt like the 1994 USC game was the moment when that season turned,” said Philyaw. “Nobody gave us a chance whatsoever, that was the turning point. When we went down there and beat them with the young guys stepping up getting their first real shot, it changed everything. USC doesn’t give anybody respect, they thought it was just a stat game, Keyshawn Johnson told me that in the tunnel, ‘it’s a stat game.’ I never forgot that, I responded, ‘yeah it will be, for me.’ I wasn’t afraid of USC, I hadn’t grown up watching them. I saw UNC and NC State as a kid, I wasn’t being disrespectful, but USC’s history didn’t mean anything to me. I’m from the south, it doesn’t make any difference to me.”

What Philyaw and company did was stomp the Trojans in their own house 22-7 with a lineup comprised of 2nd stringers. Philyaw shined with multiple long runs, none better than this 49 yard touchdown run.

“We had a bunch of guys that were filling in and felt like we deserved to be starters, it was our goal that we were going to go down there and hit ’em. It was our opportunity to showcase what we could do. SC was constantly talking trash, we had a lot of guys getting their first opportunity but we were hungry and weren’t about to put USC on a pedestal just because they were ‘SC. It took a little country boy from North Carolina to say ‘it’s just SC it doesn’t mean anything to me’ to get the rest of the guys pumped. I wasn’t intimidated, it was easier for me to come out and play hard because I had grown up watching a different tradition.”

Coaches knew Philyaw could play, but his stellar performance vs. USC on October 1st, 1994 tallying 123 yards proved that he could be relied on in-game, and a bigger role in the offense soon followed. Whittle and Philyaw began to split time evenly, and the two-headed combo led Oregon on a winning streak that culminated in the Pac-10 title and Rose Bowl berth.

Philyaw would play a vital role in achieving that team goal, scoring both touchdowns in Oregon’s 17-13 victory in the Civil War vs. Oregon State in rainy Corvallis to seal the Pac-10 title.

Even though I grew up back east, the Rose Bowl was a big deal. I used to watch those games on TV and hearing Keith Jackson’s voice, I used to imagine one day Jackson would call my name with me playing in the Rose Bowl. When I caught that screen pass and scored in the Civil War, it felt like that dream for so long was actually coming to reality.”

Philyaw would play a big role in the 1995 Rose Bowl game, as Oregon’s primary weapon of attack vs. Penn State was screen passes out of the backfield to Philyaw and Whittle. Oregon racked up 456 yards passing in the game, but came up short on the scoreboard. Still, it was a great finish to a memorable season.

“My mom got to come watch the Rose Bowl, it was the first time she had seen me play in college,” said Philyaw. “That was a big deal for me. I remember looking around at the stands, it was so packed and the energy intense. Penn State were huge, we had never played guys that big before, but we weren’t afraid of them.”

Philyaw finished the 1994 season with 716 yards rushing plus another 211 through the air, showing his versatility he had over 1,000 all-purpose yards and 11 TDs while splitting time with Ricky Whittle.

Philyaw went on to play in the NFL with the New England Patriots, Carolina Panthers, and St. Louis Rams. He participated in the 2001 XFL season, but after breaking his foot twice that year chose to retire from football. Dino Philyaw now resides in Eugene, OR and operates Philyaw’s Cookout & Catering, remaining close to the Oregon program and forever remembered for his iconic touchdown scored in the 1994 Civil War.

“Hardly a day goes by that somebody doesn’t stop me to talk about my touchdown in the 1994 Civil War,” said Philyaw, laughing. “I made other plays too, but I guess it’s great to be remembered for something.”

_____________________________________________________________________

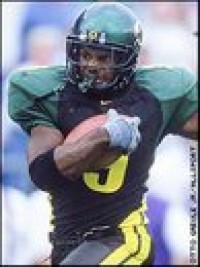

SALADIN MCCULLOUGH (1996 – 1997)

Pasadena, CA (Muir High School)

El Camino Junior College transfer (Torrance, CA)

Saladin McCullough ran a long ways before getting to Oregon, then spent two years running all over the Pac-10. 1995 Oregon was led by senior runningback Ricky Whittle, but the 1996 season brought great uncertainty to the role of starting tailback for the Ducks until McCullough emerged.

He had grown up in Los Angeles dreaming of being a USC Trojan. McCullough was a prep superstar at Muir High School and seemed destined to be the next one to assume the starting role at ‘Tailback U’ under John Robinson in 1993. He passed the SAT with flying colors, but his score raised flags among faculty and his score was eventually invalidated. Refusing to take the SAT again, he sat out a year, then attended Pasadena City College, but the lure of the local neighborhood and its temptations proved difficult for McCullough, who was suspended twice for disciplinary reasons, yet still racked up 725 yards and six touchdowns.

Looking for an opportunity to escape the old neighborhood and focus on football, McCullough transferred to El Camino Junior College in Torrance, CA, and excelled, racking up 1,829 all-purpose yards and 12 touchdowns in 10 games. But despite the great numbers and Associates Degree in hand, USC no longer wanted McCullough. They had recruited other runningbacks in the time since, not wanting to wait on McCullough the Trojans had moved on.

“I sat down with Coach Robinson, and he said that they had people on their board higher than me,” Saladin McCullough remembers, now the runningbacks coach at Pasadena City College. “I had always wanted to be a Trojan, I didn’t know what to do. So I went to 7-11 and bought a college preview magazine. I looked at Oregon and saw that they had just come off the Cotton Bowl and didn’t have a returning runningback, so I called them up. I took a trip up there, they offered me a scholarship, and I took it, I never looked at any other school. I didn’t know what to expect, I just figured I’d go up there and do my best.”

USC’s loss was Oregon’s gain. The Ducks had kept their eyes on Saladin, but knew there was little chance of tearing him away from his dream school of USC. But when USC declined to offer a scholarship, Oregon took a chance on McCullough, signing the junior college to join the team for the 1996 campaign.

McCullough arrived to Eugene amidst a crowded backfield all vying for the starting job. For Oregon’s first game the team took five runningbacks with them to Fresno State for a tailback-by-committee approach until a leader emerged. Initially it was Jerry Brown who got the majority of the carries, in the opening game McCullough only got one carry vs. FSU.

“I was freaking out because I only got one carry, the next game I got a few more, and after that the job was mine,” said McCullough.

Once acclimating to the system McCullough emerged as the clear top-talent among the challengers for the role. By mid-season 1996 McCullough was the workhorse. In the 1996 game against Arizona, McCullough scored five rushing touchdowns, propelling the Ducks to a 49-31 victory. McCullough was a touchdown machine, racking up 15 TDs in only seven games. It was a single-season record that stood until the 2008 season. However, it was a season also filled with injuries and disappointment.

“I sprained my knee and missed a few games. In the 5 TD game against Arizona I could’ve maybe gone for more, but on the last play of the 3rd quarter I injured my hamstring and didn’t play in the 4th. I wish I had redshirted once I hurt my knee, but the team really needed me out there so I rushed back and played hurt.”

But the 1996 season would have disappointing results, finishing 6-5 and no postseason bowl game. However there was hope in Eugene that 1997 could be special, as McCullough had only just started to show what he could do.

1997 was an offensive explosion for the Oregon Ducks. A vaunted passing attack led by the quarterback duo of Akili Smith and Jason Maas was accented with Saladin McCullough’s rushing heroics, and it started in grandoise fashion, with McCullough returning the opening kickoff of the first game of the season 93 yards for a touchdown vs. Arizona.

His run through the Pac-10 would continue in dominant form. McCullough was the complete package, speedy, shifty, powerful, able to catch the ball, could run between the tackles, he was the perfect all-around back for Oregon’s pro set offense. He was the most feared weapon in all of the Pac-10.

During his rampage through the Pac-10 his senior year, McCullough made the Trojans pay for their mistake with one of the most unbelievable runs in recent memory, fumbling a pitch for what appeared to be a 10 yard loss, then somehow evading eight tacklers for a 44 yard gain that left onlookers speechless, including USC coach John Robinson.

McCullough appeared to be gliding when he ran, like taking a nonchalant stroll through a park, but moving at a speed faster than anyone else on the field. He had power to run through defenders, moves to bounce around them, the speed to sprint past them, and was masterful on screen passes.

But the 1997 season was a year of growing pains. McCullough plowed through defenses, but it was a young team still finding their feet. It would be McCullough’s final game as a Duck where the Ducks began to emerge from their shells, previewing what would come in the future years. McCullough made the most of his final game, as he took the second Oregon play from scrimmage in the 1997 Las Vegas Bowl for a 76 yard touchdown run vs. Air Force.

“Patrick Johnson was my roommate, so when he scored a touchdown on the first play of the game I felt like I needed to do something too, when I scored on the second play it was like, ‘ok, hey, the roommate connection!'”

Oregon would dominate Air Force that day, led by Saladin McCullough and the emerging players that would become stars in 1998. McCullough finished his career at Oregon with eye-popping numbers. He finished the 1997 season with 1,343 yards and 9 TDs. In two years of play, 18 games total, McCullough racked up 2,028 yards and 24 touchdowns at an impressive 5.2 yards-per-carry. McCullough could do it all, and he did for Oregon, at USC’s peril.

“I wish I could have had four years at Oregon,” McCullough laments. “I never went through an offseason program before I got to Oregon, never lifted weights. I think if I had four years to be able to train I could have set just about every rushing record, LaMichael would be chasing me. I only got to go through an off-season program once, before the 1997 season. Still, I have a lot of fond memories of playing at Oregon, just hanging out with the fellas or going over to Coach (Gary) Campbell’s house to cook dinner, he’s still like a mentor to me. I’m really happy that I chose to go to Oregon. I hear from people all the time who say, ‘I never knew nothing about Oregon until you started playing there,’ that’s special to me knowing that I did my part to help put Oregon on the map.”

In an odd twist of fate, Saladin’s younger brother Sultan McCullough would attend USC and become the starting runningback for the Trojans. While his career at USC was impressive, he could not match older brother Saladin in overall production.

“I always try to set up an Oregon vs. USC bet with Sultan every year, but he’s scared, doesn’t want to bet,” McCullough laughs. “Especially these days with how good Oregon has become, he never wants to make any family bet on the game.”

Saladin McCullough proved, just as Philyaw had before him, that Oregon could find tremendous talent in the junior college ranks.

Following his career at Oregon, McCullough spent some time with the San Francisco 49ers, then spent several years in the CFL and one season in the XFL. He retired from football in 2005 after being released by the Toronto Argonauts to make room for their newest free agent signing, enigmatic NFL outcast Ricky Williams.

Today Saladin McCullough is an assistant coach with Pasadena City College, with aspirations to return to Eugene someday, this time as a coach. His son, also named Saladin McCullough, is a junior college athlete hoping for a scholarship offer from Oregon to carry on the McCullough legacy.

____________________________________________________________________

REUBEN DROUGHNS (1998 – 1999)

5’11″ 220

Anaheim, CA (Anaheim High School)

Merced Junior College transfer (Merced, CA)

Oregon’s running game had been dominant in 1996 and 1997 with Saladin McCullough at the helm, but once again 1998 loomed with questions of who would take over. Fans had heard rumors about two incoming players, freshman RB Herman Ho-Ching from Long Beach, and Reuben Droughns from Merced Junior College. After the first game of the season, it would be no question whom was taking over the reins.

Reuben Droughns was a powerful bruiser with great speed. He had chosen Oregon out of high school but didn’t qualify academically, choosing to go the junior college route he found himself at Merced JC with an opportunity to hone his skills.

“I didn’t have the grades coming out of high school, but I had the option to go up to Merced. It was the perfect situation for me to go up there and try to groom all of my skills,” said Reuben Droughns, now retired after lengthy career in the NFL that included a Super Bowl victory with the New York Giants in 2007. “I chose to go to Oregon, and I stuck by that promise after my time at Merced. I wanted to leave California, but still play schools in California. Once I saw Oregon it was done, it was a great atmosphere, it was clean and friendly and the coaches were great. It just felt like this was the place. Other schools recruited me, but Oregon was the only place I wanted to be.”

Droughns set multiple rushing records while at Merced, rushing for over 1,600 yards his sophomore year, considered the #1 junior college runningback, it was a major coup for Oregon to land such a touted player. Still, Droughns had to earn his place, and despite the early production it did not come easy. Droughns arrived in Eugene Associates Degree in hand to prepare for the 1998 season and the first opponent, highly touted Michigan State coming to Eugene for a national television broadcast. The Spartans featured superstar Plaxico Burress on offense and were led by head coach Nick Saban, now the head man at Alabama. Through summer workouts and fall camp Droughns did his best in competition to earn his place on the team.

“I went through summer workouts and camp, but I was still learning. Protections were really tough for me, it took a while to adjust to the system and get comfortable. I was scared when I made it to Oregon. Watching game tape of Michigan State seeing how big those guys were, I knew it was way beyond junior college,” Droughns remembers. “When coach (Mike Bellotti) told me I was starting the first game the fear ran through my bones, I didn’t know what could happen. I knew I was gonna get hit, but I didn’t want to make a mistake…then to come out of that tunnel at Autzen Stadium to see and hear that packed crowd, it was unreal.”

If Droughns felt nervous that opening day of the 1998 season, he didn’t show it. Oregon steamrolled over Michigan State 48-14, and it wasn’t as close as that score suggests. Leading the way was Droughns, who was still learning the playbook but dominating the overwhelmed MSU defense in every way imaginable. With a junior college transfer quarterback, Akili Smith, at the helm, Oregon pummeled Michigan State giving Saban the worst loss of his entire coaching career.

Reuben Droughns capped the game with a 75 yard touchdown run, putting him over 200 total on the day. In one game Reuben Droughns had become a team leader and the star of the #1-ranked offense in the country.

“That Michigan State game, it was so fun,” said Droughns. “For so many of us we were just getting started, Akili it was his first time starting as ‘the guy.’ It was so memorable, just the crowd and the way we played, it was amazing. I didn’t really know the system yet, the coaches basically just said, ‘Reuben, we’ll give you the ball, the endzone is over there, go run towards it.'”

Oregon’s offense averaged over 50 points a game through the first half of the 1998 season led by Droughns, who was averaging nearly 200 yards per game. The Ducks seemed to be unstoppable, and whispers of national championship contender began to spread.

Droughns was plowing through the competition, but it wasn’t until a month into the season when things started to make sense, during week 4 vs. Stanford.

“The Stanford game was probably my favorite as a Duck, it was the first game where everything started making sense,” said Droughns. “I felt like for the first time I knew what was going on, I had acclimated to the system, and everybody was on the same page. Our offense was so good that year, the Stanford game was when we really started realizing how good we could be.”

If Droughns had relied on his superb physical abilities to date, the prospect of Reuben Droughns with a full understanding of the offense and on the same page with weapons around him like Akili Smith and Damon Griffin, defensive coordinators in the Pac-10 weren’t sleeping much trying to come up with any feasible way to slow down Oregon.

It turned out the only thing that could stop Oregon was themselves. In one of the most amazing football games ever played, the 1998 matchup between Oregon and UCLA featured two top-10 teams playing in the Rose Bowl in front of a national television audience, the victor being the clear frontrunner to return to the Rose Bowl in January. The game had literally everything but the kitchen sink, including UCLA quarterback Cade McNown vomiting on the field while under center about to take the snap. A back and forth battle featured Droughns plowing through defenders when the season took a sharp down turn.

Having already racked up 175 yards rushing in the game by the third quarter, on one play Droughns fell to the ground awkwardly without being touched, breaking his leg.

Despite the broken leg, Droughns would not give up. In one of the gutsiest moves ever witnessed in recent football memory, Droughns returned to the game and continued carrying the ball on a broken leg. However the pain proved too great and eventually he was forced to exit for good, his season was done. The game would go to overtime, but Oregon would come up short that day succumbing to UCLA 41-38.

More injuries followed with Droughns being forced to watch from the sidelines, a team that had been the #1 offense in the country in September was reduced to a hollow shell of itself by the end of the year, losing to Colorado in the 1998 Aloha Bowl 51-43 despite a heroic effort by Akili Smith to carry the team, setting nearly every Oregon single-season passing record in the process.

1999 Reuben Droughns would return for his senior year, determined to make amends for his shortened season the year before. Droughns would again suffer injuries but play through them showing a grit and blue collar mentality that carried over into his lengthy NFL career. Droughns carried the team in 1999, literally, as the Ducks relied on him almost exclusively to grind out games. In one game vs. Arizona, Droughns carried the ball 45 times, a single game mark that still stands today as the all-time record for most carries in a game for an Oregon Duck.

The Ducks 1999 season would be one of transition, replacing the legend of Akili Smith and starting a new legacy as Joey Harrington took over the starting QB role from AJ Feeley at midseason. There were last-minute heroics, tough losses, growing pains and physical pain, all the while Droughns was the rock to lean on reliable to grind out the tough yards and still capable of breaking away for a long run. The Ducks would finish the year with a victory over Minnesota in the 1999 Sun Bowl.

Reuben Droughns finished his career at Oregon having played in 16 games for a total of 2,058 yards rushing and 18 TDs. No one had ever run harder in their career than Droughns, or dished out more punishment on defenders than him. Reuben Droughns was selected in the third round of the NFL draft by the Detroit Lions, the start of an NFL career that led to the Denver Broncos, Cleveland Browns, and New York Giants before retiring after the 2008 season.

Reuben Droughns will always remain a fan favorite, not just for the plays he made, but how he made them. Fearless, ruthless, the ultimate combination of both power and speed. Yet his legacy is also one of lingering questions, his leg gave out him in the 1998 season but his heart never did. Few ever ran with as much passion for the game as Reuben, and many fans still ponder the possibilities of how far the 1998 team may have gone if Reuben’s leg had been able to carry the team past UCLA that one day in Pasadena.

____________________________________________________________________

MAURICE MORRIS (2000 – 2001)

5’11″ 216

Chester, SC (Chester High School)

Fresno City Junior College transfer (Fresno, CA)

Just as they had with McCullough and Droughns, Oregon again dipped into the junior college ranks for the start of the new decade to fill the role of runningback for the Ducks. Just like Droughns, the Ducks once again found a gem in the California junior college ranks that made an immediate impact.

Maurice Morris was built much in the same way as his predecessor Reuben Droughns, big and powerful but possessing deceptive speed, willing to run through or around a defender. He grew up on the east coast, but moved west to play at Fresno City Junior College. Morris was a two-time JC Grid-Wire First Team All-American, setting rushing records two years in a row tallying 3,078 rushing yards in two seasons, completely shattering every rushing mark at Fresno City College in the process. In 1998, Morris and Texas’ Ricky Williams were the only two runningbacks in the nation to total in excess of 2,000 yards rushing in a season.

By the time his two years were up at Fresno, nearly every major university in the country wanted Morris to be their next great power back. It was Reuben Droughns who would host Morris on his recruiting trip to Eugene and to carry on the now-established tradition of transfer runningbacks at Oregon. Droughns would be gone, so the opportunity to be the man in the powerful Oregon offense picking up where previous backs had left off proved too enticing to pass up. Much like with Droughns, there was little doubt who was the best back in Oregon’s arsenal from the moment he set foot on the field.

Morris was like a carbon copy of Reuben Droughns, much to the chagrin of defensive coordinators. Morris lacked the striding grace of McCullough, in fact when he ran he looked like he had a limp, but what he lacked in style Morris more than made up for in raw power.

It was now the Joey Harrington era, a time when the Ducks found a way to almost always win no matter the odds, when the traditional powers took a back seat to the up-and-comers from Oregon. While Joey got the praise as ‘Captain Comeback’ for his 4th quarter heroics, it was Morris softening up defenses with his powerful runs gaining the tough yards.

The 2000 season with Morris toting the rock was a memorable one for many reasons. ESPN College Gameday made their first of many trips to Eugene, for the September 23rd matchup against highly-ranked UCLA. Lee Corso predicted a Duck victory, and Morris & co. did not disappoint pummeling UCLA 29-10 in front of a raucous Autzen Stadium crowd.

Morris on the year would rack up 1,106 yards and 8 TDs on the ground with another hundred through the air, helping lead the Ducks to the 2000 Holiday Bowl. The Holiday Bowl vs. the Texas Longhorns was a national showcase to prove to everyone that Oregon was a legitimate contender, and thanks to Morris’ efforts, particularly with a long touchdown catch, Oregon was able to hold on 35-30.

It was a watershed moment in program history, taking down one of the most storied programs in college football history, propelling Oregon towards the success and hype that would follow in the coming years. Oregon was now a national contender every year, a team that was discussed ocean to ocean for more than just their uniforms, these Ducks were serious, and with Morris running and Harrington’s leadership quality the sky was the limit going forward.

2001, Morris’ senior year, would see another transfer runningback added to the fold to compliment Maurice Morris’ skills. Onterrio Smith had sat out the previous year after transferring from Tennessee, a highly skilled runner with all the talents of a NFL-caliber player, but with a troubled past and disciplinary issues with Tennessee that led to his dismissal. Morris was still the man, but now Oregon had a two-headed threat in he backfield, it seemed almost unfair that the two most talented tailbacks in the entire Pac-10 conference would both be playing for Oregon.

Morris wasted no time picking up where he had left off the previous year, being a consistent chain-mover capable of carrying the ball 20+ times a game, softening up the defense for Onterrio Smith’s gashing big play ability in the 2nd half. Oregon in 2001 was the buzzworthy team across the country, spurred by a high-profile Heisman campaign for senior QB Joey Harrington and appearing on national television on an almost weekly basis. Oregon was THE team out west, a top-level program led by the powerful backfield duo of Morris & Smith that had everybody thinking national championship. Morris was the clear starter, Smith the fresh legs. But when Morris got hurt mid-season, Smith stepped into the role in dramatic fashion, as Onterrio racked up 285 yards in one game vs. WSU, setting a team record that stood until last week’s 288 performance by LaMichael James vs. Arizona.

A flukey loss to Stanford in mid-season would be the only hiccup, but it would prove enough to hold Oregon out of the national championship conversation, still thanks to Morris’ hard running the Ducks won their first outright Pac-10 title in decades and earned a berth to the Fiesta Bowl to play Colorado. To earn the title Oregon beat Oregon State in a torrential downpour at Autzen Stadium in a hard-fought low-scoring game, with Maurice Morris scoring the game-winning touchdown.

Colorado had become the talk of the college football world, having shocked in back-to-back weeks Nebraska and Oklahoma to win the Big-12. Through a fluke in the BCS calculations (which has since been fixed in the formula) Nebraska despite finishing third in their conference would play Miami in the national championship game at the Rose Bowl that year, leaving Colorado and Oregon to fight it out for #2. Based on the way Colorado had ended the season many predicted the Buffaloes to steamroll Oregon, Colorado being in the media’s mind the team deserving to play in the title game.

It didn’t take long for Oregon to prove who was the better team. Oregon’s defense completely shut down Colorado’s touted rushing attack and forced them into a pass-first offense trying to keep pace with Oregon, who through the hard running of Morris and precise passing of Harrington took a commanding lead. The Ducks controlled the game, showcasing a confident bravado and panache for the big play that had many wondering if it should have been Oregon playing in the national championship rather than Nebraska. No play better defined Oregon’s dominance that day than Maurice Morris’ touchdown run, where he rolled over a defender without touching the ground and continued down the field for a long touchdown, completely demoralizing Colorado. When the dust settled, Oregon had won 38-16.

Morris and Smith together became the first runningback tandem at Oregon to both rush for 1,000 yards in one season, leading the charge to the Pac-10 title and Fiesta Bowl victory. Never before had Oregon had such a dominant ground game, but going forward it would be Onterrio’s show. Maurice Morris finished his two years at Oregon with 2,066 yards and 16 TDs on the ground, and was drafted in the 2nd round of the NFL draft by the Seattle Seahawks. Morris continues to play in the NFL to this day, currently a backup on the Detroit Lions.

________________________________________________________________________

ONTERRIO SMITH (2000 – 2002)

Onterrio Smith became the focal point of Oregon’s attack in 2002

5’10″ 214

Sacramento, CA (Grant Union High School)

University of Tennessee transfer (Knoxville, TN)

Onterrio Smith had the skills to do anything on the football field. His speed was unrivaled, his moves jaw-dropping, his ability to plow over defenders surprising, his ability catch the ball majestic.

Coming out of Sacramento, CA, Smith set numerous rushing records in the prep ranks before deciding to attend the University of Tennessee, fresh off a national championship led by Peyton Manning the previous year. Smith’s first year at Tennessee was a tumultuous one, and after disciplinary and drug issues Coach Philip Fulmer chose to dismiss him from the team.

After sitting out a year, Onterrio decided to give “Second-Chance U” a try, to wipe the slate clean and start over in the friendly confines of Eugene, OR. Due to NCAA rules he had to sit out the 2000 season watching fellow transfer RB Maurice Morris lead the Ducks to a Holiday Bowl victory, but rumors started to spread about this new guy in practice named Onterrio that was destroying the Oregon defense.

The 2001 season brought with it much hype, and the long-awaited debut of Mr. Smith comes to Eugene. Extensive playing time didn’t immediately come though, as Oregon already had a dominant runningback demanding the ball, Maurice Morris now in his senior year. Smith showcased his talents in limited roles early in the season, but when Oregon traveled to Pullman, WA to face Washington State it became Onterrio’s time to shine. An injury to Morris put Smith in the spotlight, who ran past, around, and through the WSU defense for a school-record 285 yards, a single-game mark that stood for a decade.

Suddenly everyone was talking about Onterrio Smith, and the prospect of Smith and Morris playing together. This SEC castaway had re-emerged as a force to be reckoned with out west, no longer when Morris stepped off the field could defenses rest easy, now they had an arguably even more talented runner coming straight at them with fresh legs. For teams it was simply too much to deal with, the combo of Morris and Smith was too good, a 1-2 punch nobody could counter.

Smith, acting as the backup to Morris, led the team in rushing in 2001, racking up over a thousand yards. With the Fiesta Bowl victory and departure of Morris and Harrington to the NFL, 2002 suddenly Oregon became Onterrio’s team. Replacing two legends wouldn’t be easy, but people knew that if Onterrio was given the ball, magic could happen. Smith graced the cover of ESPN the Magazine for their college football preview, all eyes were on #2 and what he could do when no longer sharing the carries with another transfer runningback.

The 2002 season started off exactly as predicted. Onterrio Smith was the centerpiece of Oregon’s new offense, and things were rolling. Big victories also matched big numbers by Smith, and the hype campaign was in full swing for his likelihood to be a Heisman candidate. Onterrio did everything; run, catch, return kicks. Scouts drooled over the prospect of drafting him, the anticipation being that Smith would forego his senior year for a shot at the NFL.

But things would derail sharply mid-season. After leading 21-3 over ASU at halftime during a home game for the 6-0 Ducks, Oregon’s secondary collapsed as ASU QB Andrew Walter set new Pac-10 passing records leading an unbelievable comeback that ended in a 45-42 loss for the Ducks. Worse still, Onterrio Smith suffered an ankle injury that would slow his season from there, later aggravated forcing his season to be shut down entirely. Smith’s chances for the Heisman were over, and with his departure from the lineup Oregon limped through the rest of the season losing 5 of their 6 including an embarrassing defeat to Wake Forest in the 2002 Seattle Bowl.

Still, despite missing much of the 2nd half of the season, Onterrio Smith racked up 1,141 yards and 12 TDs, back-to-back thousand yard seasons. As predicted Smith chose to leave school early, and was drafted in the 3rd round of the NFL draft for the Minnesota Vikings, where he played for three years until legal issues prematurely ended his career.

________________________________________________________________________

In the time since Oregon has once more dipped into the transfer ranks, bringing in RB LeGarrette Blount from a Mississippi junior college for the 2008 season. Blount and Jeremiah Johnson would each have thousand yard rushing seasons in 2008, while Blount set the new single-season rushing touchdown mark at Oregon with 18, a record previously held by Saladin McCullough with 17 in 1997.

But things had changed. Oregon’s recruiting in the 2000’s improved thanks to the success on the field and improved facilities. No longer was it a necessity that Oregon dip into the junior college ranks as a stop-gap measure to find a runningback, now it was a luxury they could do only if a player was special enough to bring in, like Blount. Oregon would rely on runningbacks recruited from the high school ranks, to prep and mold them over time maximizing their abilities rather than thrusting players directly into games out of need like with the transfer runningbacks of the previous years.

Yet the legacy remains. For a ten-year stretch, Oregon achieved heights never before realized, thanks largely to the efforts provided by the transfer runningbacks that chose to call Eugene home for the remainder of their collegiate careers. From Dino Philyaw starting in 1993 to Onterrio Smith in 2002, the decade-long stretch of transfer RB’s at Oregon set the precedent for success, the piledrivers in Oregon’s offensive weaponry that opened eyes, wowed a nation, and proved that Oregon was here to stay.

Related Articles:

These are articles where the writer left and for some reason did not want his/her name on it any longer or went sideways of our rules–so we assigned it to “staff.” We are grateful to all the writers who contributed to the site through these articles.