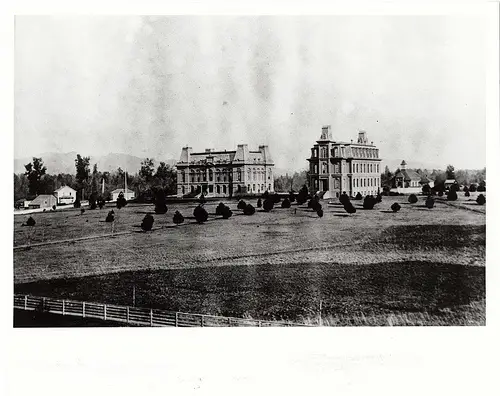

Photo of the first official day of classes at the University of Oregon, October19th, 1876. The third floor served as an athletic facility.

Ask anybody in the country today their impression of University of Oregon athletics, and three words will immediately be uttered: uniforms, Nike, facilities. Oregon’s facilities now are the envy of the country, even many pro teams don’t have the plush amenities that Oregon athletes appreciate today. It didn’t happen overnight though, and over the years of the University of Oregon’s rich history many facilities outgrew their use, many being retired, many others being used long past their usefulness out of necessity.

Villard Hall and Deady Hall stick out in the pastoral lands of the University of Oregon campus circa 1901

With all the talk about facilities, let’s take a look at the history of the venues that have housed the athletes of Oregon past and present, and all it has taken to rebuild the University of Oregon campus from humble old place of learning to athletic jewel of the west.

1873 construction of Deady Hall began, the start of the University of Oregon. Four years later a baseball game was held between UO and Monmouth College. In the first inning Monmouth scored 17 runs, an inauspicious start for the Webfoots, marking the beginning of many more days of sorrow, and some of great triumph and glory, to follow over the course of the next 145 years to present day.

Initially the third floor of Deady Hall was reserved as a men’s gymnasium, but the construction of a gym in 1881 replaced the need for this space. In 1890 a larger gymnasium was constructed, housing men’s athletics (all male students were required to exercise twice a week). By 1909 a new gymnasium was built to house men’s athletic, while the 1890 gym became the women’s gym. It burned down in 1922.

Organized athletics were still in its infancy at the time, while back east collegiate football had been played for some time, in the west collegiate athletics barely registered. The first Oregon football game took place in on March 24th, 1893, in an open field in the shadows of Deady Hall, where Oregon (coached by Cal Young) defeated Albany College 44-2.

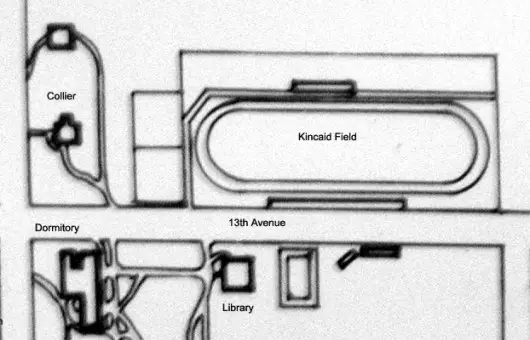

Around this same time a running track was built at the corner of 13th and A Street (now Kincaid Street), as indicated on this campus map from 1894.

1894 campus map. Things have changed quite a bit in the past 118 years…

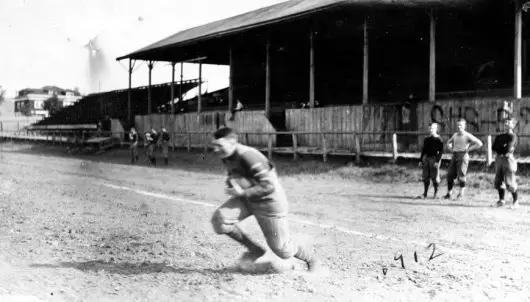

This track would become the site of the first official Oregon athletic facility, Kincaid Field. Bleachers were constructed in 1902, with the university acquiring the property along 13thavenue for an all-purpose venue to hold the Webfoots football and track&field events. Students helped construct the bleachers that would hold the crowds that cheered on Oregon’s highly successful football program in those early days led by coaching legend Hugo Bezdek. With more sports being added (women’s tennis became Oregon’s first female sport in 1909) and collegiate sports gaining in popularity, the need for more buildings to house Oregon’s athletics was apparent. To facilitate larger crowds for big events, often football games were held in Portland at Multnomah Field for matchups that were expected to far exceed what the stands at Kincaid Field could hold.

The pinnacle of these early days came in 1916, the Webfoots football team finished with a 6-0-1 record and represented the Pacific Coast Conference in the 1917 East-West Tournament Game, later known as the Rose Bowl. Oregon defeated Penn in the 1917 East-West Tournament Game 14-0, putting Oregon on the map as a powerhouse in collegiate athletics on the west

coast. With Hugo Bezdek as coach of the Oregon football, baseball, and basketball teams and the school’s first athletic director, the Webfoots were formidable.

A plaque now marks the site of Kincaid Field

With the success of the Bezdek era came increased crowds, and it became clear that Kincaid Field could no longer keep up with demand, construction began on a larger facility to house Oregon’s football and track programs, Hayward Field. Built in 1919, its inaugural season saw Oregon’s football team continue its dominance, once again representing the PCC in the 1920 East-West Tournament Game.

The new facility was named Hayward Field to honor the track coach and trainer Bill Hayward (Oregon track coach 1903-1947) during a ceremony on November 15th, 1919 during the game against bitter rival Oregon Agricultural College (now Oregon State). The Webfoots won the game 9-0, but the ceremony honoring the longtime coach Hayward with the name of the facility was noticeably absent one person, Bill Hayward. Nobody had bothered to inform him in advance of the ceremony taking place, and he was back in the locker room providing treatment for the football team at the time. Coach Hayward did not discover that the new stadium had been named after him until he read about it in the newspaper the following morning.

Hayward Field replaced Kincaid Field in 1919 for football, and added a track in 1921

In 1921 a six-lane cinder track was added surrounding the football field to allow for track events, marking the end of Kincaid Field’s usefulness. With Hayward Field now capable of holding football and track&field events, Kincaid Field was closed in 1922. A plaque near the northwest corner of the Museum of Art commemorates the athletes who competed at the site where Kincaid Field once stood.

While construction of Hayward Field was taking place, nearby another building was also taking shape, Gerlinger Hall. Built 1919-1921, it replaced the “old gym” as it was known as a new place to house women’s athletics. The timing turned out to be rather apt, as the old gym burned down in 1922.

The gymnasium, built in 1890, housed many of Oregon’s athletics, before a new gym was built in 1909 and this became the women’s gym. It burned down in 1922.

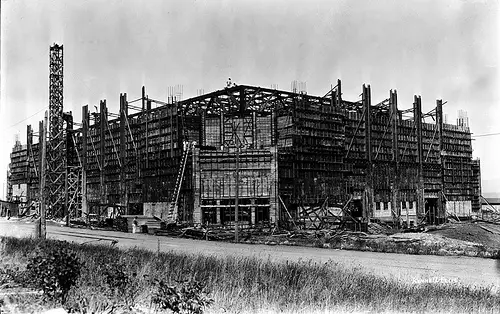

While football and track enjoyed the cozy confines of their new facility, basketball was facing an arena issue of its own, its popularity far exceeding the space available in the men’s gymnasium. Starting in 1926, construction of a new facility to house basketball and other athletics began, McArthur Court.

McArthur Court was a grand multi-purpose facility, named after Clifton McArthur, prominent UO athlete and first student-body president who later became Congressman McArthur. By 1927 the new building was complete and ready for its debut, a 38-10 victory over Willamette University on January 14th, 1927. The new arena featured a capacity in excess of 6,000 (later expanded to seat over 9,000) and athletic offices in the lower level, it was a huge step forward in athletic facilities at the time for the university, though its construction cost was sizable. To fund the construction a $15 fee was added by the Associated Students of the University of Oregon, once finally paid off students held an extravagant “mortgage papers burning” ceremony to mark the end of the imposed arena fees.

In 1937 repairs were made to the roof. Other improvements followed in the 40s and 50s, including the addition of the familiar exterior steel support structures above the roof. Mac Court, or “The Igloo” as it was originally nicknamed later to be known as “The Pit,” proved valuable well past its expiration date. Only recently replaced by the construction of the Matt Knight Arena, it was the centerpiece of Oregon athletics for almost 85 years, becoming the second oldest collegiate basketball arena in the nation behind only Fordham University’s Rose Hill Gym.

For decades minor projects continued, improvements here and there, some older buildings demolished for new structures, but the athletic arenas remained relatively intact. Hayward Field hosted football and track&field, Mac Court had basketball, Gerlinger Hall housed women’s athletics.

But by the late 1950s, it was obvious that football had outgrown Hayward Field and a new stadium would need to be built, even with Oregon playing typically only three games a year on campus at Hayward. In 1959 the university purchased 90 acres of land on the north side of the Willamette River. By 1966 construction was underway for a new stadium, the new mecca of Oregon football, Autzen Stadium. Completed in 1967 just days before the first game slated for September 23rd, 1967, the design instituting an artificial crater with the removed dirt forming the slopes that the grandstands were built upon.

Oregon lost the first game held at Autzen Stadium 17-13 vs Colorado in 1967

John Harrington was Oregon’s starting quarterback for that first game, a close 17-13 loss to Colorado. Years later John’s son Joey Harrington would become arguably the most iconic student-athlete in the history of the program through repeated triumphs in the stadium his father helped open. Autzen featured a grass surface in its first two years of existence, but with the wet climate it was determined it would be far easier and cheaper to replace it with artificial turf.

Finances were a big issue, stark contrast to today’s athletic program. The university in the 1970s and 1980s was strapped for cash, and Autzen Stadium proved to be a financial boon for the program, acting as a host for many summer concerts that would help fund the athletics in the fall. Often it was the student-athletes directing traffic in the parking lot or acting as security at events while artists such as the Grateful Dead and Bob Dylan would rock Autzen.

Meanwhile with football now vacated from Hayward Field, it became a full-time track & field facility. The track was expanded to 8-lanes, and altered to an all-weather rubber surface. With these improvements and the track program flourishing under legendary coach Bill Bowerman and buzz emerging from a brash young runner named Steve Prefontaine, it was decided that Hayward should host the Olympic Trials in 1972. Hayward Field would again host the Olympic Trials in 1976 and 1980, and following an expansion/renovation in 2004 the trials returned to the holy ground of track & field in the city commonly referred to as Tracktown U.S.A. In 2012 Hayward Field will once again be the site where athletes make their first step towards Olympic glory with the trials, scheduled to take place at venerable Hayward Field June 22nd – July 1st.

Women’s basketball made its debut inside Mac Court in 1974, but facing harsh budget cuts Oregon’s successful baseball program had to be cut in 1980. Football was also on life support, dealing with NCAA sanctions for rules violations and the sub-par facilities of the woefully small weight room behind the east endzone bleachers as part of the Barker Stadium Club expansion in 1981, and the locker rooms under the west endzone consisting of little more than three hooks and wood planks for each player. It was clear that fundraising efforts would be needed to put Oregon in a position to be competitive with the rest of the conference. So bad was Oregon’s football team in the 1970s, that there was talk of kicking them out of the Pacific Conference.

It was then that Oregon Athletic Director Bill Byrne developed a novel concept, to make money it was necessary to spend money. Funding was raised for several projects to improve facilities that could then in turn fund further construction, beginning the cycle of modern Oregon athletics as we know it. Better facilities would mean better recruiting, get better athletes to come to Oregon and the improved athletic play would lead to larger crowds, resulting in increased revenue.

It began with the sky-suite complex along the north rim of Autzen Stadium in 1988, moving the press box to the south side under the roof providing space for luxury suites that would serve as the prime financial support for future facilities. Costing $2.3 million to build along with a million dollar press box on the opposite side, it was the first step towards transforming Oregon athletics from the antiquated humble cash-strapped program into the national powerhouse Oregon athletics have become.

The revenue earned through the leasing of the sky suites helped to fund the epicenter of Oregon athletics, the Casanova Center. Located outside of Autzen Stadium, it was built to house all the athletic offices, replacing the overcrowded space beneath Mac Court. Named after legendary coach and athletic director Len Casanova, it was expected to cost over nine million for its construction as part of a 14 million in total planned package to improve Oregon’s athletic facilities, paid for through state bonds and fundraising efforts, but costs inflated to over twelve million before its official dedication on September 27th, 1991. The new home to Oregon’s locker rooms, weight rooms, coaching offices and meeting areas, it didn’t come without controversy, as many in the community balked at the aesthetic additions to the grounds, such as sculptures that cost thousands deemed unnecessary by many.

Coinciding with the unveiling of the Cas Center, Autzen’s carpet also got an upgrade, removing the old Astroturf for a new Omniturf, designed to lessen the impact and turf-burns commonplace of the era from the hard artificial surfaces. The concerted efforts to upgrade Oregon’s facilities coincided with improved on-field play, as Oregon fans reveled in Oregon’s first trip to a bowl game in 27 years when the Ducks won the 1989 Independence Bowl in Shreveport, LA. This was followed the next year with an appearance in the 1990 Freedom Bowl, and it seemed like the program had turned the tide of the ugly days of consistent losing for decades.

Oregon’s athletic programs now had the means with which to compete on an even plane, and compete they did. Oregon went from perennial cellar dweller to one of the most prominent programs on the west coast, and Autzen and Mac Court gained reputations as two of the loudest and most hostile environments for an opposing team to enter.

But costs were mounting, and facing budget cuts a controversial solution was proposed to offset expenses. Oregon Sports Action began in 1991, legalized gambling on professional sports as a means to fund public university athletic programs. While hindered with legal hassles from the get-go, Sports Action did provide much needed funding to the Oregon athletic program.

The watershed moment of this renaissance came in 1994, when the football team, picked to finish 9th in the conference that year, won the Pac-10 conference and was invited to play in the 1995 Rose Bowl, the school’s first appearance in the prestigious game since 1958. The Ducks would lose to Penn State in the Rose Bowl, but the enthusiasm for Oregon sports created in the wake of that run to glory was undeniable. Donations to the program flooded in, season ticket sales soared, suddenly there was nothing cooler than being an Oregon Duck.

Following an impressive 10-win season the next year that ended in bowl disappointment once more, a conversation between head football coach Mike Bellotti and prominent alum and Nike CEO Phil Knight would spark a movement lifting Oregon from being simply on par with their competition to pulling away from the pack with state-of-the-art facilities the envy of the world. Following Oregon’s embarrassing loss to Colorado in the 1996 Cotton Bowl, Knight asked Bellotti what was needed for Oregon to remain competitive. Bellotti responded that they needed an indoor practice facility.

Three years later, Bellotti had his indoor practice facility, and the rest of the conference began taking notice. The Moshofsky Center opened in August of 1998 just in time for football season, sporting a complete artificial turf football field, a 4-lane running track, climate control, medical facilities, and batting cages. Not only did it service student-athletes, but on gamedays “The Mo” as it is known became a hotspot for fans as well, providing space for food vendors and other gameday events catering to the fans, it has come to be called the world’s largest indoor tailgate party. Inside the stadium fans were treated to something that had long been desired at Autzen Stadium, a video replay screen.

New turf was also installed in Autzen Stadium, and with the program now financially stable there was no longer a need to hold concerts or other events inside Autzen to balance the budget, Autzen would be the house of Oregon football and nothing more going forward. The final concert held at Autzen was in 1997, featuring U2 and Rage Against the Machine. A Rolling Stones concert had been discussed a few months later, but the university declined, angering many in the community when news of the refusal became public.

Outside the Moshofsky Center, sections of the Autzen parking lot were converted to football practice fields, soccer and lacrosse fields. The construction of the Moshofsky Center and the surrounding facilities did help improve Oregon compete with the top echelon of athletic programs across the nation, but it was not without its outspoken critics. An outcry over the excess of spending on athletics while education programs were being ignored or outright cut at the university fell on largely deaf ears, and an arms race began that continues to this day. Oregon builds a new facility, competing schools counter with an indoor practice facility or stadium improvement of their own.

The relationship between Nike and Oregon has blossomed in the time since that post-Cotton Bowl conversation between Knight and Bellotti, starting with a focused marketing effort on branding Oregon. It worked. Over time the attempts to market the University of Oregon athletic program have increased in flash and innovation, from new uniforms to promotional campaigns. Through Nike’s efforts working with the University of Oregon, the Ducks have gone from the laughing stock of the west to the most innovative futuristic program in the country, everyone knows about the Ducks, everyone wants to be like the Ducks. If imitation is the greatest form of flattery, then the U of O is clearly the cool kid everyone is trying to follow, and with it the Ducks have gained not only a financial foothold to support the various sports but can recruit top-notch athletes on a national level.

Additional upgrades continue to be made. In 2002 Autzen Stadium was renovated, expanding seating to 54,000 and further improving amenities available within the stadium. So too were Oregon’s football locker rooms inside the Casanova Center, as well as improved treatment facilities and weight rooms.

The Jaqua Academic Center provides the best academic support structure for student-athletes in the country, and renovations to Hayward Field will permit the grand old mecca of track & field to continue to host national competitions. The construction of PK Park east of Autzen Stadium signaled the return of the baseball program to Oregon athletics. Further construction of the Casanova Center is currently underway, adding additional meeting rooms and state-of-the-art technology components to further prepare Oregon athletes for their competition.

Last year the newest upgrade was completed, with the opening of the Matthew Knight Arena. Several years in the making with multiple mis-steps and hitches before its final completion, the arena replaces the beloved but well-past-retirement McArthur Court as the new home for Oregon’s indoor athletics. It already in its short lifespan has hosted multiple concerts, a tennis tournament, and was highlighted by the Oregon men’s basketball team CBI Tournament Championship.

Once the scrappy but underfunded little guy, Oregon now is the big dog. A program once hopeful to win a few games each year, the Ducks now have transformed over time into the home of innovation, new technology, the athletic elite. So is it the facilities or the athletes that have led to Oregon’s vault into national prominence? Perhaps both, the success on the field of athletic competition is determined through the effort given by the person behind the uniform, but by providing elite level facilities and great coaching (a hallmark of Oregon for over a hundred years as a coaching factory and stability in the various sports) it affords the modern Oregon student-athletes the tools needed to give their absolute best effort.

(all photos used courtesy of the Knight Library and UO special collections archive)

Related Articles:

These are articles where the writer left and for some reason did not want his/her name on it any longer or went sideways of our rules–so we assigned it to “staff.” We are grateful to all the writers who contributed to the site through these articles.