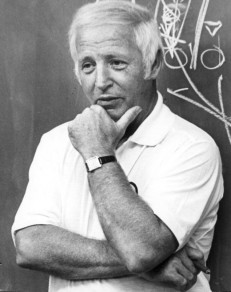

In 1959, Oregon was only a year removed from its first Rose Bowl appearance in 39 years. Coach Len Casanova had, after three losing seasons to begin his tenure from 1951-54, built the Ducks into a consistent winner.

In 1959, Oregon was only a year removed from its first Rose Bowl appearance in 39 years. Coach Len Casanova had, after three losing seasons to begin his tenure from 1951-54, built the Ducks into a consistent winner.

Although the 1958 season had been a disappointment, with Casanova’s team going 4-6 in its conference-title defense, the team’s greatest victory that year was a 25-0 shutout of mighty USC in Portland. So when the Trojans needed to fill their coaching staff for 1959 following two losing seasons, they turned to Casanova’s assistant, John McKay. Then, as today, the conference’s balance of power had shifted—however temporarily—from Los Angeles to Eugene. If they couldn’t beat the Ducks, the Trojans would incorporate them.

A star halfback for the Ducks, who had played alongside Hall of Fame quarterback Norm Van Brocklin, McKay would have been a prime candidate to succeed Casanova, but the 54-year-old coach wasn’t going anywhere; after 1958 Cas would coach eight more seasons in Eugene. The then 36-year-old McKay’s move away from his alma mater in ’59 more than paid off. Trojans head coach Don Clark only lasted one season after McKay came to the Los Angeles, and in 1960 McKay was hired as USC’s head coach (over future Oakland Raiders coach and owner Al Davis, also an assistant there). Within two years, the Oregon grad would guide the Trojans to a national championship, the first of four titles McKay’s teams would win between 1962 and 1974, cementing his legacy among the all-time college football coaching greats.

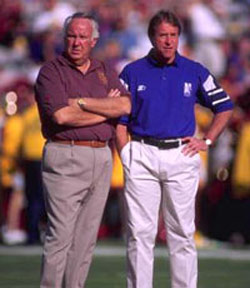

Though Trojans history includes great teams and players from nearly every era, the one coach who stood alongside the great John McKay before the arrival of Pete Carroll was John Robinson. Also an Oregon alumnus, Robinson had played on Oregon’s ’58 Rose Bowl team and joined Casanova’s staff one year after McKay’s departure, in 1960.

For 11 years on the Casanova and Jerry Frei staffs from 1960-71, Robinson guided Oregon’s offense and helped legendary quarterbacks like Dan Fouts and Bob Berry flourish. He too could easily have succeeded Casanova, but Cas (in his new role as athletic director) chose offensive line coach Jerry Frei instead. How differently might Oregon have fared under Robinson instead of Frei? It’s hard to say, because Frei is viewed as an excellent coach despite his firing after five seasons. But there’s no doubting the impact Robinson went on to have in Los Angeles instead.

Robinson had first joined McKay’s staff in 1972, staying for three years, and in ’75 was working as an assistant for the Oakland Raiders under his childhood friend and former Oregon teammate, head coach John Madden. (Madden began his college playing career as a Duck before transferring to Cal Poly.) When McKay decided to leave for the NFL’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers, USC turned to Robinson.

Just as he could have succeeded Casanova as head coach in 1967, Robinson could easily have wound up back in Eugene running the team in 1972 or 1974, when Oregon was replacing Frei and Dick Enright. But his departure from Eugene after the 1971 season had been somewhat bitter. After Oregon had finished 5-6, Frei was told he wouldn’t be fired if he agreed to replace his assistant coaches. Robinson had already accepted an assistant coaching job under McKay at USC, but Frei still refused to replace assistants like George Seifert, who would go on to win two Super Bowls as head coach of the San Francisco 49ers. Robinson would have known first-hand that the Oregon program was experiencing too much internal strife to be successful, with alumni and the athletic department battling for control. Instead of losing and being second-guessed in the Willamette Valley rain, he could be supported in the SoCal sunshine amidst a recruiting gold mine and a matchless football legacy. And indeed, Robinson would go on to with a national championship of his own by his third season as USC’s head coach.

It took Oregon years to regain the momentum it had lost, for the years either McKay or Robinson was an assistant at Oregon (1950-58, 1960-71) represent some of the best seasons the Ducks put together before the program rose to prominence in the mid-1990s. McKay had a losing record as an Oregon assistant coach, at 36-51-4, but that includes years with Casanova rebuilding  the team in the early 1950s. During McKay’s final six years in Eugene, the team went 31-27-3. Robinson’s 11-year tenure saw Oregon compile a mark of 52-46-5. Neither of those marks made them world beaters, especially by today’s standards in Eugene. Yet these coaches were, with Casanova and Frei, the foundational elements of Oregon’s rise.

the team in the early 1950s. During McKay’s final six years in Eugene, the team went 31-27-3. Robinson’s 11-year tenure saw Oregon compile a mark of 52-46-5. Neither of those marks made them world beaters, especially by today’s standards in Eugene. Yet these coaches were, with Casanova and Frei, the foundational elements of Oregon’s rise.

It’s also worth noting how history has changed, and the turning point arguably came in 2000. Oregon had just finished with a season-ending top ten ranking in the Associated Press poll for the first time, after a Holiday Bowl victory over Texas. USC was looking for a new head coach to succeed Paul Hackett. The Trojans offered the head-coaching job to Mike Bellotti, who considered accepting before ultimately turning USC down. The next year, 2001, Bellotti’s Ducks would win their first January bowl game since 1917, a Fiesta Bowl trouncing of Colorado that was, before 2010’s undefeated regular season and national championship game appearance, the greatest in Oregon football history.

USC ended up just fine after Bellotti’s decline: they hired Pete Carroll, who would lead the Trojans to two national titles (one shared with LSU) before the team was later stripped of them. But what if Bellotti had taken the USC job? Sure, the Ducks would have still had Joey Harrington under center and a deep, talented roster in 2001. But would Oregon have won the Fiesta Bowl that year with, say, his former assistant Jeff Tedford as head coach? Likely not.

Today Oregon’s head coach is considered by many to be the greatest mind in all of college football. While it’s likely that Chip Kelly will someday leave Eugene to coach elsewhere, it’s overwhelmingly likely that it won’t be for USC. Although the Trojans will always have a greater recruiting base in their namesake Southern California than the Ducks will have in Oregon and the Northwest, the USC job is, despite the program’s continuing winning tradition, no longer so much better than coaching in Eugene. If Kelly leaves, it will be for the NFL.

It may be true that Oregon can never equal the football legacy of USC. It would take 20 straight Duck victories over the Trojans to equal the all-time series, and the Trojans show no signs of succumbing to a multi-year slumber (even if Lane Kiffin is no Pete Carroll). But consider this: before 1994, the magical Rose Bowl season in which Oregon’s program was all but reborn, the Ducks were a collective 10-32-2 against USC. Since 1994, the Ducks are 8-6, even though those years have been some of the Trojans’ best. A century of history can’t be re-written, but the thing about history is that it continues to unfold.

Related Articles:

Brian Libby is a writer and photographer living in Portland. A life-long Ducks football fanatic who first visited Autzen Stadium at age eight, he is the author of two histories of UO football, “Tales From the Oregon Ducks Sideline” and “The University of Oregon Football Vault.” When not delving into all things Ducks, Brian works as a freelance journalist covering design, film and visual art for publications like The New York Times, Architect, and Dwell, among others.