Say what you will about the Oregon men’s basketball team, but one thing is for certain: they get buckets. Oregon currently ranks 11th in the nation in points per game with a whopping 83. So, how exactly do they do it? The Ducks run a mean transition offense that consistently gets men to the rim or open looks from the arc.

A transition offense is, simply, the transitional stage from defense to offense. Depending on each coach’s strategic scheme, different teams will transition in different ways. For Oregon, whose legion of speedy players are all capable of running the floor, coach Dana Altman chooses to go with an intense, up-tempo transition offense.

Altman’s aggressive approach does several things for his team. First, it tires out the opponent. The Oregon men are well-conditioned, thus capable of constantly running a break. Many opposing teams, however, are not always prepared to guard a high-octane transition offense for two halves.

Second, it does not allow the opponent to set up a half-court defense. In college basketball, where the zone prevails, teams can often find themselves suffocated by a smart D, but with quick transitioning there’s no time to set-up.

Third, a fast team is a fun team. Much like Oregon football, fans would rather watch our boys put up 100 points rather than 50, any day. Ergo, through a combination of these factors, Oregon is able to score in a variety of ways, consistently.

Although the Duck transition offense looks sporadic and improvised at times, it is actually rather fundamental. There are many minute pieces of the transition offense that could be analyzed, but for the sake of brevity, we’ll look only at how Oregon excels at filling the lanes.

In transition, the lanes refer to the middle area, the left wing, and the right wing. If all lanes are filled correctly, the floor should be spaced enough for an easy bucket. A lot of teams teach their players to fill the lanes, but Oregon players do it with the best.

Middle Lane

The middle lane is typically filled by the first big man up the floor – the 4 or 5 that doesn’t get the rebound. Although it seems as though their job is to just run straight, it is a tad more complex. Above we see forward Mike Moser heading towards the rim as the ball remains within his peripheral vision. Although Johnathan Loyd is on the right wing (ball highlighted in green), he is still looking at Moser as an option.

The middle lane filler must work as both a diversion and an option. Also, as they run through the middle, the point guard or ball handler should be following the large path they leave behind. All the while, this big man should be keeping his eyes on the ball and always looking to score. If they have not received the ball by the time they reach the block, their job is to post-up in hopes of an inside look or a rebound/put-back.

Left Lane

The left lane filler, who is typically the 3, should ideally have triple-threat capabilities. To be a triple threat means to be able to shoot, drive, or pass. Luckily for Oregon on the play above, their best scoring option Joseph Young is streaking down the left side. His job is to run the floor as fast as possible looking for the ball. On this play, we see that Young has actually outrun the opposing team’s transition defense and should be open for a long bounce pass from Loyd.

Right Lane

The right lane filler’s role is practically identical to the left lane fillers, except they are usually a 2-guard. In this play, however, the transition D has pretty much caught up with the O. So, the lane filler must make a decision. If the ball handler drives, he should pop to the corner for an open 3. If his man denies him the ball, he should cut back door for a layup. And lastly, if the spacing is right and the ball handler has nowhere to go, he should look to get the rock himself and take it to the rim off a quick first step.

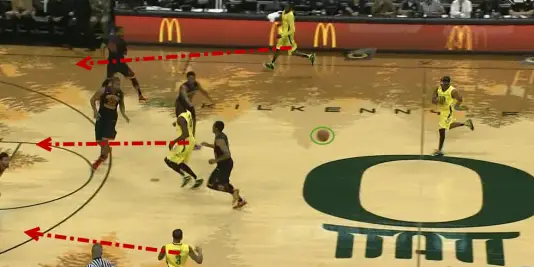

All Together

If all the players fill their lanes correctly nobody should have to fight for spots or accidentally bring their defender onto a teammate, as the spacing is now ideal. As seen above, all lanes are being filled and Loyd is already making a pass towards the left wing. With everyone in their place and the defense off balance, Young makes a hard move to the basket, as a well-timed back screen is set for him. This allows him to not only draw contact for a foul but get the bucket in transition as well.

1 Man Fast Break

Every now-and-again the ball handler beats the lane-fillers up the floor. In this case he may have put himself in a predicament. If he slows down to wait for his teammates he may pass-up an opportunity or even get picked from behind, but if he attacks the rim or pulls up he may miss the shot and ruin the transition altogether. In this play, though, skilled guard Jason Calliste decides to put his defender on ice and drive the basketball for an easy two points.

Oregon’s quick transition works so well it’s almost cheating. The Ducks may not win every game but they will give their all trying, and (usually) score 80 points along the way. Although filling the lanes is only part of the process, it is vital for a team do so if they wish to imitate Oregon’s scoring prowess. And as long as Oregon continues to do one thing well and remains true to their scheme, they’ll be getting buckets.

Basketball is, simply, a complicated sport.

Related Articles:

Seven Offensive Coordinator Candidates for the Oregon Ducks

Five Candidates to Replace OC Marcus Arroyo

Coach Jim Mastro: The Perception, and the Truth

Has Oregon Turned the Corner on Offense?

Ducks, Taggart Punish Beavers; Earn Bowling Trip

Textbook Defense, Herbert's Return Energize Duck Victory; Civil War Next

Lawrence Hastings spent the first fifteen years of his life in Los Angeles, California before moving to Eugene, Oregon. Transitioning to Duck land was easy for him seeing as he was raised a Pacific Conference fan since birth. So Lawrence, loving his new green home, chose to pursue a Sports Business degree at the University of Oregon. In his spare time Lawrence plays and watches sports religiously, with a particular passion for basketball. His favorite Duck of all time is Aaron Brooks, whom he met at local basketball camp as a teenager.