Welcome to this week’s edition of X’s vs. O’s. Today we return to the “picture book” format! The concept we are discussing today is another new idea that has spread like wildfire throughout the collegiate ranks in recent years.

However, like most “new” things in the world, it is simply a combination of two very old ideas. In this case, the pairing of a counter trey run scheme with a sweep read stresses the defense in ways the two schemes could not if they were ran as separate plays.

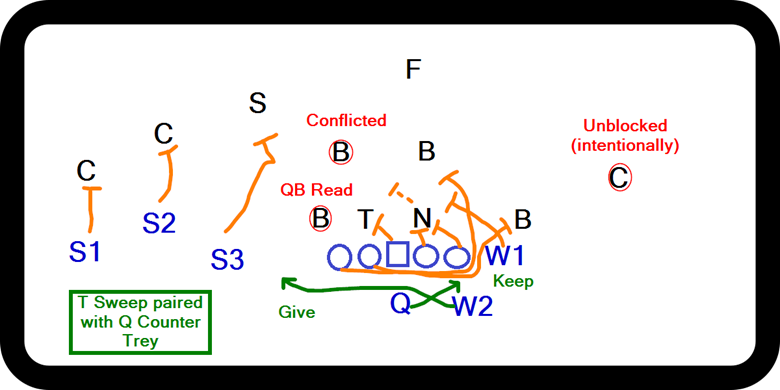

T Sweep paired with Q Counter Trey.

The blocking on this play is a gap scheme. A gap scheme consists of down blocks by the playside blockers, a kick-out block on the playside EMLOS (End Man on the Line of Scrimmage), and a backside puller who blocks the first off-color (defensive player) to show to the playside.

In the above diagram, the center, playside guard, playside tackle, and the tight end are executing down blocks. This is the mantra for down blocks: “Gap, On, Linebacker”. The blockers will first look to block their backside gap and then any player lined up over them.

If a defender doesn’t fit either of these designations, the blocker looks for an away-side linebacker. The purpose of the downblocks are to carve out a running alley to the playside by using a drive block technique.

The kick-out block and the “skip” pull, executed by the backside guard and tackle, respectively, are tasked with prying open the playside gap that the runner will use to gash the defense.

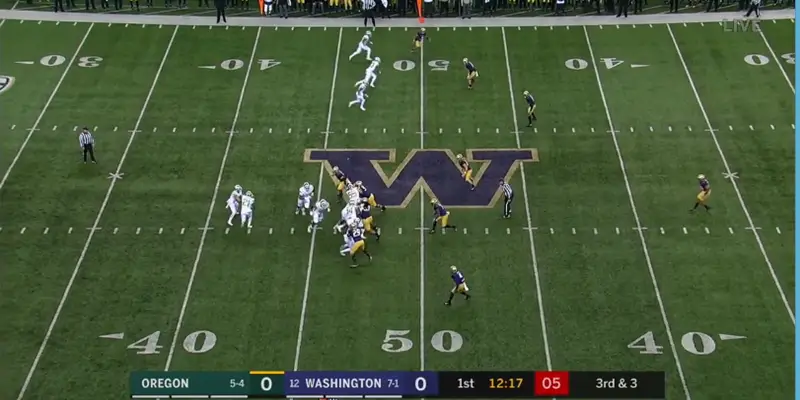

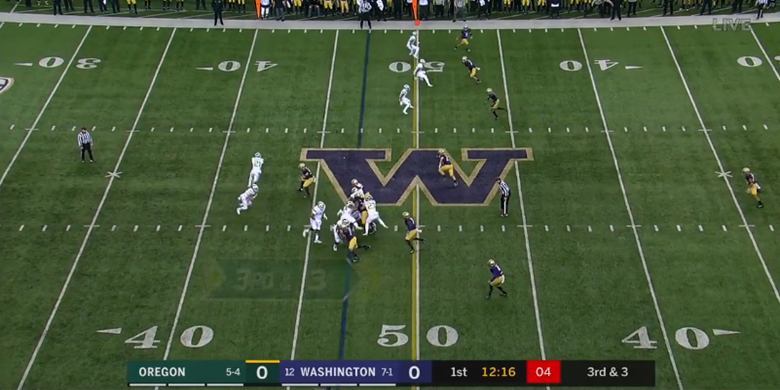

The Defensive Alignment At The Snap.

When the backside tackle and guard both pull on a gap scheme the concept is commonly referred to as “Counter Trey.” In the above photo, you can clearly see the backside tackle and guard begin to pull to the playside. The playside offensive lineman, as well as the tight end, are executing their down block assignments.

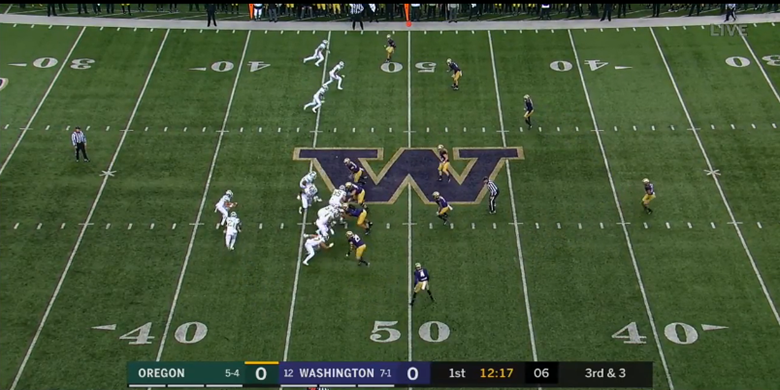

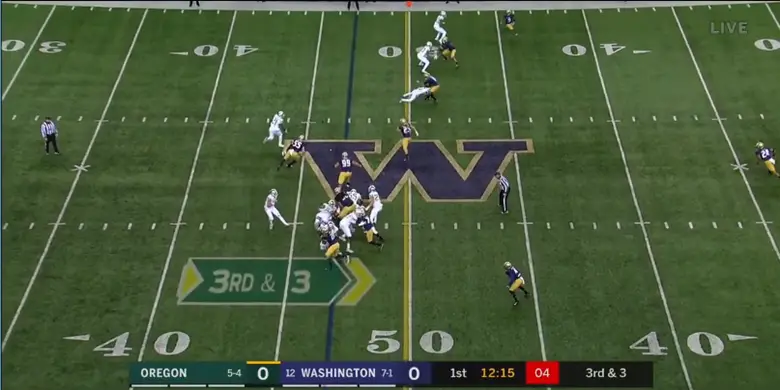

The QB Reads The EMLOS For His Give/Keep Read.

The second half of this combination scheme is a sweep read. Like a traditional read-option, the quarterback is reading the EMLOS on the backside to determine whether to give the ball, or keep and follow the pulling linemen.

In our example, you can see the defender “sat” in his gap, playing the quarterback, leaving space for the running back after the handoff. The three wide receivers will “stalk” block the defensive backs at the top of the image. This leaves the running back one-on-one with a linebacker.

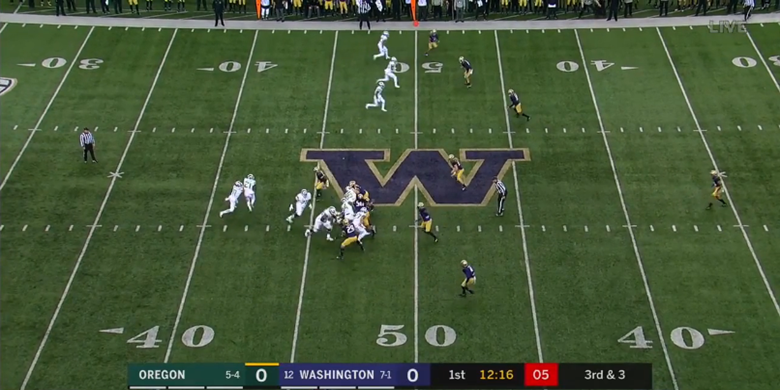

It’s A Footrace!

Now, let’s discuss the conflicted linebacker, who is right in the middle of the purple “W” logo in the above photo. Given that the EMLOS forced a handoff, the strong side linebacker is now responsible for the running back on the sweep. If the quarterback had kept the ball and run to the counter trey action, the backer would then be involved in the run fit to the playside.

When the offense pulls blockers across the formation, they create “new” gaps that the defense must account for in order to avoid being outnumbered at the point of attack. The linebacker here actually recognizes the sweep fairly quickly, but all the Oregon back needs is a step…

The Boys In Blue Are In Hot Pursuit!

The spread offense looks to create these slight moments of hesitation and conflict to gain an edge on every snap. Incremental advantages can quickly snowball into sustained drives. Elite athletes operating in open space are provided a better opportunity to generate explosive plays, and create one-on-one matchups. These are founding principles of the modern spread offense.

Taggart’s offense continues to impress with it’s formation variety, use of motion, and versatile running attack. Even in a down year, I have enjoyed watching his offensive system in action. I’m confident brighter days are ahead. Thanks for joining me for another edition of X’s vs. O’s. Enjoy the bye week!

Zach Pierson

Birmingham, Alabama

Top Photo from Video

Zach enjoys dissecting football gameplans and schemes from the confines of his home office on the outskirts of Birmingham, Alabama. His goal is to provide breakdowns that shed light on the intricacies of football, using simple, easy-to-understand language.