My friends, on Mario Cristobal‘s coffee table in his office in the Mo Center is a big book about Oregon football history that was written by Brian Libby, a professional writer who contributes a guest article from time to time to FishDuck.com. He gives us a perspective that few can, with his incredible knowledge of Our Beloved Ducks. He is also a very intense fan and is truly one of us! Charles Fischer

It was a time of screaming, crying and head-shaking in disbelief. It was a time of jumping up and down and running in circles maniacally. It was a time to collapse on one’s knees.

And that was just the first 60 seconds in my living room as the Rose Bowl went final.

Maybe this wasn’t a National Championship Game like the Ducks played for in January of 2011 and 2015. Maybe it wasn’t the best Oregon Ducks squad of all time, nor even the best of the decade. Heck, the 2019 team arguably wasn’t even the third-best Oregon squad of the decade.

But make no mistake: it’s pretty hard to beat the feeling of winning the Rose Bowl, especially when it represents a moment of, not just victory, but redemption.

While Clemson and LSU will play for the national title tomorrow in New Orleans with the eyes of the college football world watching, that stage itself — grand and glittering as it may be, and for a bigger trophy — is just not as special as Pasadena, California on New Year’s Day, the sun setting over the San Gabriel Mountains in America’s greatest stadium. It’s the year-end contest that has by leaps and bounds the most storied tradition.

There is nothing like the Rose Bowl …

Even in an age when the College Football Playoff has diminished the relevance of the marquee January 1 bowls (the Rose, Sugar, Cotton, Orange and Fiesta), unless the every-third-year rotation has them hosting a Playoff semifinal, the “Grandaddy of Them All” still carries a distinct flair. The Rose Bowl is like that effortlessly elegant guy in a Mercedes-Benz sitting next to luxury Hyundais and Chryslers. They may all have leather seats, but one just has a lot more class and style than the others.

The Oregon Ducks have now played 126 seasons. Only six of those seasons have ended with wins in a New Year’s Six bowl: 1916, 2001, 2011, 2012, 2014 and 2019. For those who like analytics, that’s 3.8 percent of the time. Winning a Rose Bowl has been even rarer: just four times in 126 years (or 3.2 percent). Personally, I put losing the National Championship Game in 2010 ahead of those seasons in terms of achievement. Playing for the title, win or lose, is the one achievement that supersedes winning a Rose Bowl (or any of the other New Year’s Six). And 2014 was obviously both: a Rose Bowl win and a national championship-game loss. But, at most, that makes seven seasons that have been historically great (or only 5.55 percent).

Another measurement we could look at is how 2019 compares to other seasons in terms of year-end rankings, either in the AP Top 25 or the Coaches Poll. Entering the Rose Bowl ranked sixth, the Ducks are guaranteed to finish with the program’s 10th appearance in the Top 10, along with these seasons: 1948 (after losing the Cotton Bowl), 2000 (Holiday Bowl victory over Texas), 2001 (Fiesta Bowl win over Colorado), 2008 (Holiday Bowl win over Oklahoma State), 2010 (lost National Championship Game), 2011 (Rose Bowl win over Wisconsin), 2012 (Fiesta Bowl win over Kansas State), 2013 (Alamo Bowl win over Texas) and 2014 (lost National Championship Game).

The Oregon defense could have given LSU a greater challenge than Oklahoma’s did.

The other question at this point, though, is if the Ducks will finish in the top five. It would require Oregon leapfrogging Oklahoma, which was blown out in the Playoff semifinal against LSU. But it would probably also require that the Ducks hold off Georgia, which torched Baylor. Is Oregon better than Oklahoma? I think so. Is Oregon better than Georgia? I’m not sure. But if the Ducks finish in the top five, it would be for the sixth time in program history, after 2001 (2 in both polls), 2010 (3), 2011 (4), 2012 (2) and 2014 (2).

As a life-long Duck fan, I’ve also asked myself this week, “How does this one rank in satisfaction?” Again, this is where the redemption part comes in.

Of course, it wasn’t just that the Ducks finished 4-8 three years ago. On paper, it may have been a relatively steady climb back: to seven wins in 2017, nine last year (including a Redbox Bowl win). But considering these seniors actually played for three different head coaches in four seasons — Mario Cristobal for two, Willie Taggart and Mark Helfrich for one each — it’s even more impressive to have survived that tumult, especially considering that from 1976-2008, Oregon had only two head coaches.

Yet amidst that journey to redemption, I also suspect that the Ducks found a way to turn a weakness into a strength. Constant coaching turnover has the potential to drag a program down by miring it in quicksand: the program is always changing directions but never moving forward. Key players will often transfer to other schools, as well. However, if those dangers can be avoided, I think there’s a hidden asset in having three different coaches recruiting players to the same squad; it can produce a diverse pool of talent that one coach may never have been able to assemble alone.

One of the many heroes of the Rose Bowl, Troy Dye.

Consider it this way: Mario Cristobal has been able to recruit better than arguably any Oregon coach in history, especially if you give him some of the credit for Willie Taggart’s very good recruiting class, but his prize recruits have tended to be line players and defensive players. Mark Helfrich, on the other hand, was the one who brought in the two MVPs of 2019: Justin Herbert and Troy Dye. When I think of 2019, part of me will always remember that Mark Helfrich may have been fired, but his recruits were both the MVPs and the unquestioned leaders of the team on the field.

And speaking of Willie Taggart, the Rose Bowl win also means that it’s time to forgive the head coach who abandoned the Ducks after one season. Don’t get me wrong: I rooted for Florida State to lose, too. Coaches willing to break the unwritten rule that you never take another job after just one year are usually doomed to fail. But we can’t celebrate this Rose Bowl trophy without calling each of the preceding three seasons a step in that journey.

That means Willie Taggart’s name has to be added to the credits rolling at the end of this movie. That means we have to wish him well at Florida Atlantic University and understand that his leaving Eugene wasn’t just one colossal middle finger to Oregon, but an understandable choice at the time, which in hindsight, probably even he would admit was wrong.

Even so, it’s quite something as a Duck fan to consider the rarefied air this puts Mario Cristobal in. Consider this: Rich Brooks never won a Rose Bowl; Mike Bellotti never won a Rose Bowl; and Len Casanova never won a Rose Bowl. Cristobal joins Hugo Bezdek, Chip Kelly and Mark Helfrich as the only Oregon coaches to reach the historic Promised Land of Pasadena and come away victorious. It wouldn’t be fair to make these four the Mt. Rushmore of Ducks football, because those other coaches did foundational things for the program and posted far more wins overall. But it says something significant about Cristobal only two years into his tenure as head coach.

Coach Helfrich won a Rose Bowl and got Oregon to the National Championship Game.

At the same time, given how a coach like Mark Helfrich rose and fell, it’s worth asking ourselves: if Oregon finished the 2121 season at 4-8, would Cristobal deserve to be fired? After all, Helfrich got fired just two years after taking the Ducks to the National Title Game and helping a three-star recruit win the Heisman Trophy. Maybe firing Helfrich was the right call because it allowed 2016 to lead to 2019. But it set a precedent that could someday have a negative effect. Even Cristobal can’t call himself secure like Bellotti or Kelly did. That’s the one price we still pay for firing Helfrich. What if Cristobal’s alma mater, Miami, comes calling in a year or two? Or the NFL? Cristobal might base his decision on how much freedom he has to fail, now and then.

What’s also extra invigorating about this Rose Bowl win is how it potentially changes the narrative. It was starting to feel like we could tie a bow around the years 1994 through 2014 as one continuous climb, and that post-2014 was the inevitable descent — not necessarily into a losing program, but a mediocre one again, relegated to play in tradition-less, manufactured toilet bowls like the Redbox before mostly empty seats. But in reality, there are always ebbs and flows.

It’s easy to forget that between taking the Ducks to the Cotton Bowl in his debut season of 1995 and winning the Fiesta Bowl six years later, Mike Bellotti’s Ducks spent a couple of seasons at 6-5. Moreover, before taking Oregon back to a top 10 finish in 2008, Bellotti had overseen a losing season of his own. So now as a decade has concluded, and Oregon didn’t have just a few glory years at the beginning. This program book-ended the decade with trophies.

If those decade bookends naturally connect Cristobal to Kelly and Helfrich, I actually find myself thinking more about that magical 1994 season and how this 2019 team, arriving 25 years later, resembled that Rich Brooks-led squad.

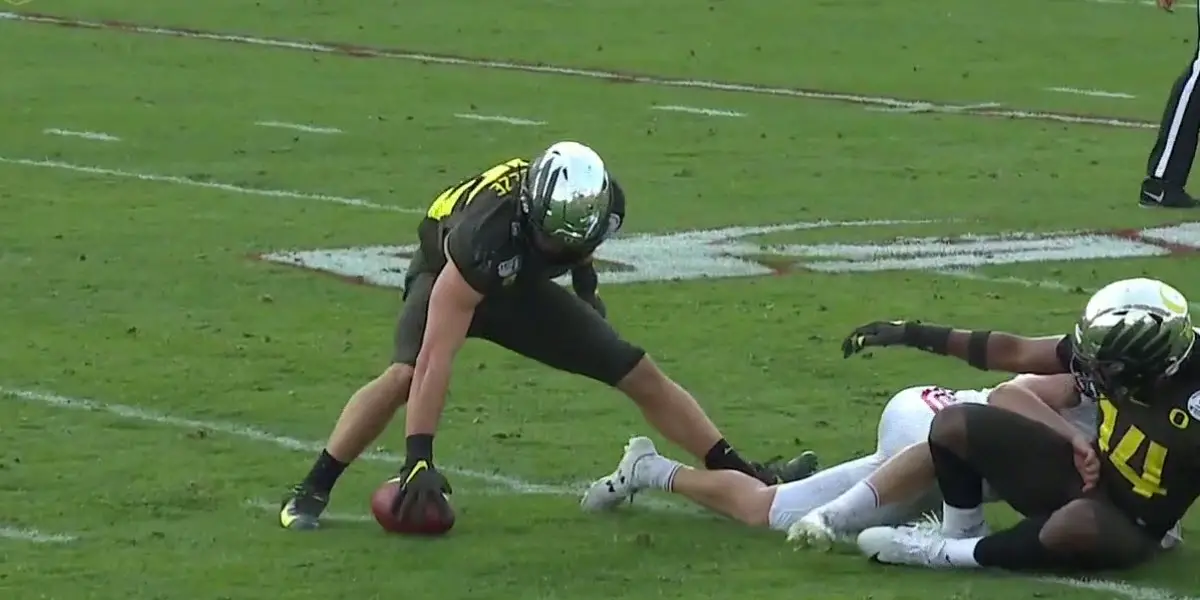

The famous “Scoop and Score” of Brady Breeze.

Brady Breeze, the hero of this Rose Bowl, represents the real DNA connection to the ’94 team as the nephew of the great strong safety, Chad Cota. That’s especially refreshing given how many offspring of ’94 season players wound up playing at other Pac-12 schools: Jered Weaver (son of Jed) at Cal, Elijah Molden (son of Alex) at Washington, Vavae Malepeai (nephew of Silila, Tasi and Pulou) at USC. But the connection isn’t just about genetics. It’s about how they played football.

Back in 1994, no matter how many yards Danny O’Neil threw for, it was the defense that got the Ducks to the Rose Bowl. 2019’s squad is every bit the equal of Gang Green. Back in 1994, it also took some really close wins to seal the deal, including a Civil War that was closer than it should have been. Back in 1994, there were times when the offense could score a lot of points, but there were also times when the Ducks could win a game by the score of 10-9, as they did in come-from-behind fashion against highly touted Arizona.

The 1994 season also reminds us that there is an inextricable relationship between a defense’s ability to be great and the approach an offense takes. It wasn’t just unfortunate or a coincidence that Oregon teams in the Kelly-Helfrich era sometimes gave up a lot of points. It was because the offense tended to score so quickly that the defense hardly got a rest. When you’re as good as Oregon’s offense was from 2009-14 or so, that’s mostly okay.

But those teams always eventually met a defense that could stop them, be it Stanford during the regular season or Auburn and Ohio State at the end. Cristobal’s 2019 squad wouldn’t beat the nation’s top teams, and he’s arguably way too focused on running the ball up the middle. Yet Cristobal is right that controlling the line of scrimmage, engaging in some modest ball control now and then and enabling great defense along the way may ultimately be the truer route to a future national championship.

Marcus Mariota was one of the few winning QBs for Oregon in the Rose Bowl.

I feel a little silly at this point because I’ve barely mentioned Justin Herbert at all. But without a doubt, the kid from Eugene has joined the pantheon of heroic Oregon quarterbacks: names like Norm Van Brocklin, Dan Fouts, Bill Musgrave, Danny O’Neil, Akili Smith, Joey Harrington, Dennis Dixon, Darron Thomas and Marcus Mariota (perhaps among a few others).

Herbert didn’t put up impressive passing stats in the Rose Bowl at all. He didn’t throw a touchdown pass, and Wisconsin led Oregon in not only passing but first downs, rushing, total yards and time of possession. But you know what? Danny O’Neil had a record passing day in the 1995 Rose Bowl, and we all would trade that record for a win over Penn State. Herbert has what O’Neil wanted and what we wanted: the trophy. And while he didn’t throw for much in this game, no one doubts what a great passer he is and what a good leader he has become.

Herbert didn’t necessarily own the identity of the comeback artist like Joey Harrington. He may not throw the bomb like Fouts, have the Xs-and-Os knowledge of Musgrave or the astonishing athleticism of Mariota. But he has pieces of all of those great predecessors. And he did something that Mariota and Harrington, despite their own January-bowl glories, never had a chance to do: he led the Ducks from a losing season all the way back.

Oregon fans received in the Rose Bowl what they lusted for during the season: a running quarterback!

As Herbert’s college career ends, there are four years of memories to look back on and a tumultuous journey that makes this Rose Bowl win all the sweeter. But in the end, I will always remember five words, which I will have to type using the all-caps button in order to evoke broadcaster Chris Fowler’s call of Herbert’s winning touchdown run:

“QUARTERBACK IN THE CLEAR!”

When I repeat the phrase to myself, it sounds a little bit like the most famous game-call phrase in Oregon history, courtesy of Jerry Allen: “Kenny Wheaton’s gonna score!” Maybe that play still stands tallest because it enabled the 25 years of glory that have followed. But Fowler is right: Indeed you are in the clear, Justin. And at least for now, so are we.

Brian Libby

Portland, Oregon Top Photo by Scott Kelley

FishDuck Note: Brian is a professional writer who contributed this for fun, but he did write a wonderful book about Oregon football that I highly recommend for you and for your Duck fan friends as a present. Being so busy, he cannot write for us often, but I am a big fan of his work and am very grateful. Charles Fischer

Related Articles:

Unbelievable...Same SEC Stuff, Different Day

Why Oregon Football Always Belongs in the National Conversation

The B1G Won the 2026 Coaching Carousel...Big-Time!

Continuity? Lanning's Hiring Success is Put to the Test

Why Whether Dyer Was Down or Not...Doesn't Matter

How to Analyze Football Talent Like a Pro

Brian Libby is a writer and photographer living in Portland. A life-long Ducks football fanatic who first visited Autzen Stadium at age eight, he is the author of two histories of UO football, “Tales From the Oregon Ducks Sideline” and “The University of Oregon Football Vault.” When not delving into all things Ducks, Brian works as a freelance journalist covering design, film and visual art for publications like The New York Times, Architect, and Dwell, among others.