Spoiled. Of the hundreds of words spoken on that show, it was the one that resonated. Yet, unlike most sports talk shows, that label wasn’t thrown at a player, but this time aimed at fans. Not the fans of the opposing team, either, but the very fans of the team around which the program centered.

It was an episode of CSNNW’s ”Talkin’ Ducks” following the first UO game that Autzen Stadium had failed to sell out since 1999. When the topic came up of why Oregon failed to sell out, various theories were debated by the panel. That it was Labor Day weekend (which hadn’t prevented every other Labor Day game during the streak from selling out), that it was an FCS opponent (ditto) or even that concerts six hours away might impact attendance.

When it was former Oregon quarterback Joey Harrington‘s turn to address the question, he could have given an answer along the lines of, “Demand didn’t exactly equal supply for tickets as the result of a price point set by the athletic department to place an emphasis on maximizing gate revenue over guaranteeing capacity attendance.” That would be the succinct, correct, boring answer. What did he think was the cause of the less-than-capacity crowd?

“People are spoiled. Duck fans are spoiled. Let’s be honest. Let’s call a spade a spade.”

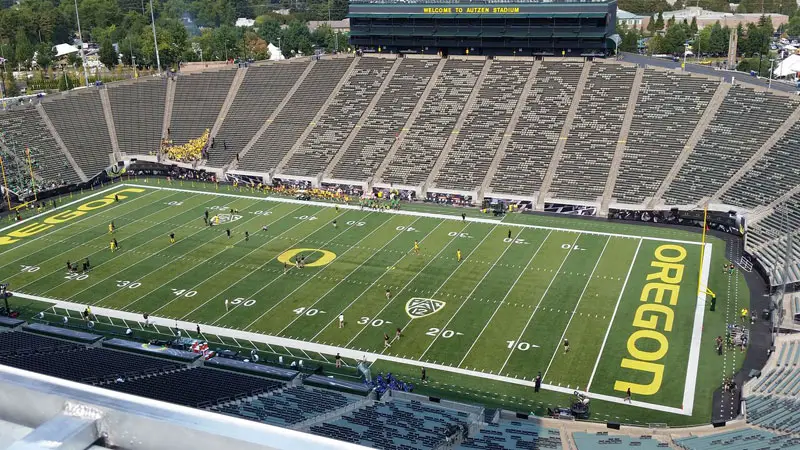

Photographic rendering of attendance against UC-Davis (approximation).

Based on his comments to the Statesman Journal last fall, I assume the target of Harrington’s comments were not the generational die-hard fans but rather the fair-weather fans whose only loyalty to any given team is dependent on the game’s outcome. (We need a good name for these types of fans, like “Drakes” or “Chesneys” or something.) Those fair-weather fans have piggy-backed on Oregon’s recent success. Unfortunately for the less-funded die-hards, many people in that group tend to have money, or at the very least are willing to pay more for a ticket.

With more fans came higher demand for seats and with it a dilemma for the athletic department: keep prices lower to reward loyalty and guarantee sellouts or increase prices to a threshold that would allow for a capacity audience but not guarantee it in the event of demand shift. Given that no team in the history of sports has ever chosen the former, it was inevitable which direction the pricing model was going.

The risk involved with that strategy is that the team has to stay competitive or it will lack a guaranteed revenue base to fall back on. If that price is pushed past the brink of elasticity, even the slightest hiccup can result in a loss of revenue. A hiccup like, say, suffering the biggest halftime collapse in bowl history in the game prior to the one it is trying to sell out.

So, for the Davis game, the price was too high for some die-hards, the team wasn’t ranked high enough for some fair-weathers but 53,817 people decided the cost of a ticket was worth it. Oregon has had a certain amount of success, and that success has generated interest. Prices were set based on that interest, and purchases were made based on that value. After 17 years, the market for Oregon tickets discovered what its equilibrium is, with supply finally outpacing demand, however narrowly.

Fans who stayed home missed the debut of Oregon QB Dakota Prukop.

If you want to know what spoiled looks like, you would want to find a team that has gone so long without finding its equilibrium, one that has experienced so much success historically that it doesn’t even know where its place is in the sport. That would be the only two schools that had longer sellout streaks than Oregon: Notre Dame (going on 43 years) and Oregon’s opponent Saturday, Nebraska (54 years and counting.) While their sellout streaks are held as banners of fan loyalty, they are also the two fan bases who have demonstrated some of the most outsized expectations in college football.

Nebraska fans love their Huskers, and have shown it by selling out every game going back to 1962, the first year of legendary coach Bob Devaney‘s tenure. Devaney was succeeded by his offensive coordinator, Tom Osborne, and the pair combined for five national titles as head coach from 1962 to 1997. For 35 years, Nebraska was as good as any team in college football. However, Nebraska hasn’t won a conference title since 1999 – only two years after Osborne retired in 1997.

The last time Nebraska won a national championship, former Oregon OC Scott Frost was its QB.

Despite the lack of success, Nebraska has sold out every game during that stretch. While some might characterize that type of purchasing power as a sign of loyalty, that loyalty hasn’t come without a mountain of expectations and demands.

Osborne was replaced by offensive assistant Frank Solich, who went 58-19 at Nebraska, and to date has won the school’s only conference championship since Osborne’s departure. But after going 9-3 in 2003, he was fired as head coach by athletic irector Steve Pederson who stated, “I refuse to let the program gravitate into mediocrity.”

Sadly for Huskers fans, it did anyway. Pederson hired Bill Callahan, whose 27-22 record was the chief reason Pederson and Callahan both are no longer there. Next came Bo Pelini, defensive coordinator under Solich, to replace Callahan, whom Pederson had passed over on the previous hire to instead land Callahan. Pelini led the Huskers to nine wins or more all seven seasons in Lincoln, which was deemed insufficient for a coach at that program. Pelini was then replaced by Mike Riley, who has won more than nine games just once in his college coaching career.

Nebraska fans endured all that for nearly two decades and still continued to sell the stadium out. The 35 years before were so good that 19 years later, despite the lack of top-end success, they are still expecting the program to be an elite contender. A fan base that has so overvalued the financial value of ticket that Saturday’s game, a matchup of teams with a combined 15-11 record last season, that the “get-in” price, the cheapest ticket available, is $200. That’s the seventh-most expensive game in college football this season. The six games ahead of it are all matchups of two teams who have been ranked in the top 11 at some point in 2016.

When demand makes the price of ticket that high despite the team not even being ranked? That’s a case of a team so spoiled by success it quantifies this matchup with marquee prices, even if the game is no longer hosted by a marquee team.

Oregon sideline vs Virginia.

The end of the sellout streak prevents Oregon from ever dealing with that delusional state. Fans sold out the stadium when the team was good and the games were affordable, and it sold out when the Ducks were great and expensive. But fans have shown they won’t accept good and expensive.

It’s now up to the program to decide which team it wants to be.

Top photo from video

Nathan Roholt is a senior writer and managing editor emeritus for FishDuck. Follow him on Twitter @nathanroholt. Send questions/feedback/hatemail to nroholtfd@gmail.com.