Eugene, Oregon, despite its predominantly white demographic, has long been a place proud of its diversity and equality. “Keep Eugene Weird” is the popular common slogan used today, though a place where people are allowed to be themselves judged by their actions not the color of their skin or other unfortunate societal misconceptions and stereotypes of the past shouldn’t be a weird concept but a welcome one. Though not without its occasional unfortunate checkered marks in the history books, Eugene has overwhelmingly been a welcoming place for people of all backgrounds to gather uninhibited by their differences.

So too is this true in the history of University of Oregon athletics, where from an early era long before it was deemed popular did the Webfoots feature black athletes. With February being Black History Month, it seems proper to focus on the trailblazers at Oregon; Robert Robinson and Charles Williams, the first two African-American athletes to compete at the University of Oregon.

As organized collegiate and professional sports began to emerge in the later half of the 19th century, black athletes were involved from early on. The first professional black baseball player was Moses Fleetwood Walker in 1884, 63 years before Jackie Robinson broke the 20th century color barrier. Charles W. Follis, better known as “The Black Cyclone,” was the first African-American professional football player, a key cog with the Shelby Blues from 1902-1906 of the Ohio League.

When the NFL was established in 1920, nine black players appeared on rosters, including Frederick Douglass Pollard. “Fritz” Pollard is in both the College Football Hall of Fame and NFL Hall of Fame for his efforts, both on the field and in overcoming adversity. Pollard was the first black head coach in professional football, leading the Akron Pros in 1921 as a player/coach. After him there would not be another black head coach until Art Shell was hired by the Los Angeles Raiders in 1990. Pollard also holds the distinction of being the first black athlete to play in the Rose Bowl, when his Brown University team lost to Washington State in 1916, only the second Rose Bowl game ever held (then known as the ‘East-West Tournament Game’).

Coach John “Cap” McEwan was ahead of his time.

In fact, black athletes’ involvement in college football stretches back even further, predating the professional sports pioneers. In 1892 William H. Lewis became the first black college football player named to the All-American team, a standout at Harvard. That same year, the first game was played between two black colleges, a 5-0 victory by Biddle College (now known as Johnson C. Smith University) over Livingstone College. However, college and professional sports remained predominantly white, societal injustices and pressures of the day often unfairly barring them from regular participation.

While many African-Americans had been active contributors to athletics in the 19th century, something changed in the early stages of the 20th as many sports barred blacks from participation, while other organized sports simply frowned upon it. By 1934 there were no black athletes left in the NFL, nor would any return until 1946 when the Rams, desiring to leave Cleveland for the sunny confines of Los Angeles, signed an agreement to play their games in the Coliseum, grudgingly accepting a clause in the contract stipulating that the team MUST be integrated if they are to call Los Angeles home. Thus with the signing of Kenny Washington and Woody Strode, both UCLA players, the barrier had been broken in the NFL, a year before Jackie Robinson did the same in baseball.

College football did not experience the same kind of outright banishment that professional sports did, however it was not exempt from blatant racism either. Black collegiate athletes were the exception, not the norm. Alabama was the last holdout, not permitting a single black scholarship student-athlete until 1970 when Bear Bryant signed Wilbur Jackson. Within three years, one third of the Crimson Tide’s football roster was comprised of black athletes.

While the University of Oregon was not the first school to feature black student-athletes, in the greater scheme of things amidst the unfortunate inequality that permeated the nation prior to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, Oregon was far ahead of the curve.

In 1926 two Portland, OR residents came to Eugene for their academic and athletic pursuits, Robert “Bobby” Robinson and Charles Williams. They were recruited by new Oregon head coach John J. McEwan, an All-American in 1914 at Army, the school where he later coached 1923-25.

At the time freshmen were not allowed to play on the varsity team, so McEwan would have to wait a year for Robinson and Williams to shine on the field, the first two black athletes at the University of Oregon.

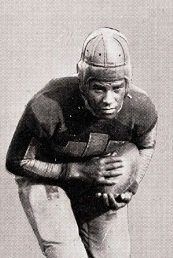

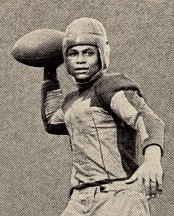

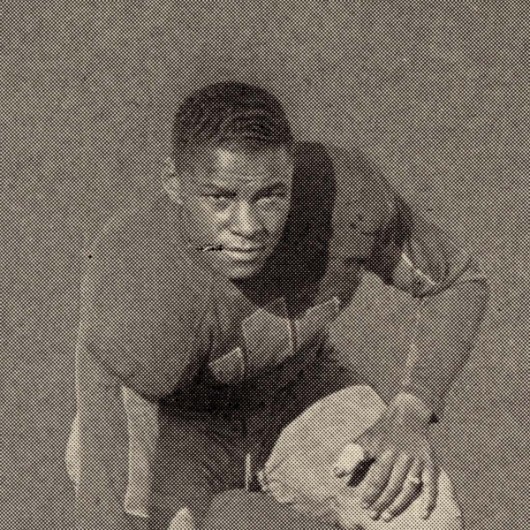

Robinson was a multi-sport star at Jefferson High School in Portland, a gifted halfback on the gridiron and pole-vaulter on the track, as well as baseball and basketball. Williams meanwhile was a bruising runner in his own right coming from Washington High School in Portland. Both were high school friends and rivals, both selected First Team All-City their senior years, and both packing the stands at Multnomah Field on gamedays with eager fans fanatically following their athletic performances.

Together, the two of them would help Coach McEwan usher in a new era at Oregon, both in success on the field and in a far more important way off of it, paving the path for other minority student-athletes to compete at the University of Oregon.

It was not without its difficulties though, as both Robinson and Williams were initially barred from living in campus dorms, having to find housing in off-campus apartments during their freshman year. Their white teammates signed a petition and submitted it to the school under protest demanding that their fellow players be allowed to live on campus in the dormitories alongside their peers. By their sophomore year the university relented, allowing Robinson and Williams to reside in Friendly Hall, albeit separated from others and permitted to enter the building only through their own designated entrance. On road trips too they were segregated from the rest of the team, not permitted to stay in the team hotel, though Williams later confirmed that despite the separate living quarters both managed to mingle with their fellow students and teammates just fine. Often on road trips after check-in at a hotel their white teammates would sneak them into the hotel anyway to stay with the rest of their fellow Webfoots.

Change was afoot at the UO, not only in accepting black athletes, but also in name. Oregon had long been nicknamed “The Webfoots,” but a student vote would give way in 1927 to a new identity: the Oregon Ducks, selected over other choices such as “Timberwolves” and “Fighting Lumberjacks.” Change too occurred in appearance, as the blue and occasionally purple colors that often adorned Oregon’s uniforms were dropped in favor of green and yellow attire. Around campus a handful of students were creating the first ever student-made full length film thanks to some cameras on loan from Hollywood, a silent movie titled “Ed’s Coeds.”

However, success on the field did not immediately follow. The first two seasons were not kind to Coach McEwan, as the glory days of years past under Coaches Hugo Bezdek and Shy Huntington had led into rough times for the Webfoots. Unable to hang onto their prominent position of west coast powerhouse after Huntington resigned, Oregon was not drawing quality talent to the program the way they once had. Since Huntington’s departure after the 1923 season, Oregon had faded into down years under coaches Joe Maddock and R.S. Smith (Smith had previously coached Oregon in 1904 as well) managing to muster only a 7-11-5 record.

Handed a relatively bare cupboard, Coach McEwan did something revolutionary for the time, going even beyond having black athletes on the roster. With Robinson and Williams on the team ready for the 1927 season, McEwan chose to place both at quarterback, putting the ball in the hands of his gifted athletes. In fact Williams and Robinson were used all over the field to maximize their talents. Robinson played quarterback, halfback, receiver, defensive back, and returned punts and kickoffs. Williams played fullback, halfback, quarterback, and defensive back.

Not only were Robinson and Williams the first African-American student-athletes at the University of Oregon, but excluding black colleges, Robinson and Williams may in fact have been the first African-Americans to ever play quarterback at a major college, though a lack of substantial records prevents 100% confirmation of this. It would be decades until the concept of a black athlete playing quarterback would be considered acceptable, the ignorant stereotypes associated with the intangibles of the position, thought to be too complex for black athletes to handle, were thankfully shattered with record-setting hall of fame careers by legends like Warren Moon and Randall Cunningham in the 1980s and 90s.

Coach McEwan wanted to win, and had proven himself a winner at Army before joining Oregon. He was determined to do so by any means necessary, regardless of any social stigmas associated with placing black players at the forefront of his teams leading the charge in a prominent position like quarterback. The best way to success in McEwan’s mind was to put the ball every play in the hands of his best athletes, and in 1927 clearly Robinson and Williams were the cream of the crop.

1927 started off well enough with the Portland duo on the field with the varsity team for the first time. Wins over Linfield and Pacific had the Oregon Webfoots/Ducks thinking that the tide of recent losing had turned, but a 0-0 tie to Idaho followed by four straight losses to end the season dashed those hopes. Despite the 2-4-1 season, Robinson and Williams shined in their roles of team leaders, regardless of their ethnicity and the opinions of some biased outside observers.

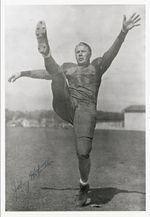

1928 brought a remarkable turnaround and return to national attention for Oregon, led by a new addition from far off Harrisburg, PA, John Kitzmiller, who earned the nickname “The Flying Dutchman.” Kitzmiller would take over the reigns at quarterback that season, moving Robinson full-time into the backfield alongside Williams, though due to political pressure they rarely lined up on the field at the same time.

John Kitzmiller became a 2nd team All-American at Oregon

With the 1-2 combo of Williams and Robinson as ball carriers and the direction of Kitzmiller, Oregon put together a 9-2 campaign, succumbing only to Stanford and Cal. It was the first time in school history that nine wins had been reached, a feat that would not be surpassed until Oregon racked up 10 victories in 2000.

The Ducks ended the 1928 season with two victories in Hawaii, first against a non-collegiate all-star team on Christmas Day, followed up a week later by a win over Hawaii, 6-0. The triumphant win in the tropics earned Oregon the title “Champion of the mid-Pacific,” a moniker given the team during the national radio broadcast of the game, a rare live event for the era.

With Kitzmiller leading the way and the talented Robinson/Williams duo pounding the rock, Oregon had amassed more points in their 45-0 opening day victory over Pacific than they had accumulated all of the previous year. However some in the community had objections to both Robinson and Williams being on the field at the same time, and Coach McEwan often had to grudgingly adhere to pressure from the administration to abide by these unfortunate requests.

Oh, there were racial slurs and negative epithets depicting the duo to be sure, common of the era in a time when the Ku Klux Klan was prevalent in the state of Oregon. However the vast majority of students and fans embraced the talented Robinson and Williams, praising them for their efforts on the field and the classy manner with which they took their adverse conditions in stride.

While Kitzmiller had become the face of the program’s return to relevance, it was Robinson and Williams at the forefront of the fireworks. In the fourth game of the 1929 season while hosting Washington, exactly 65 years and two days before Kenny Wheaton made his legendary interception against the hated Huskies, Bobby Robinson made a nearly identical play, intercepting a pass at the goal line and returning it down the sideline for what would have been an easy touchdown unopposed…had Washington player Larry Westweller not come off the bench onto the field to tackle Robinson as he streaked down the sideline. Referees awarded Robinson a touchdown anyway, and the Ducks cruised to a 27-0 victory.

Expectations were very high for the 1929 campaign at Oregon with the trio of Robinson/Williams/Kitzmiller, many thought that the Ducks could win the Pacific Coast Conference title earning a trip to the Rose Bowl. Alas they could not get past Stanford, racking up a 6-1 conference record heading into the last three games of the season vs. Hawaii, St. Mary’s, and Florida. Worse still, Kitzmiller had broken his leg the week prior vs. Oregon Agricultural College (now Oregon State), though the Ducks had managed to end their 3-game losing streak to the hated OAC with a 16-10 victory in the Civil War.

With Kitzmiller out for the rest of the season, it fell back to Bobby Robinson and Charles Williams to pick up the slack, leading the team through the final three games. A 7-0 victory over Hawaii at home had the team at 7-1 thanks to an impressive defensive effort, but the good times would not last. Oregon suffered a 31-6 loss to St. Mary’s, a powerhouse at the time given the nickname “the Notre Dame of the west,” though the 6-points scored by Oregon were the only points given up all season by St. Mary’s. Licking their wounds, Oregon traveled cross-country by train for the final game of the season to play the Florida Gators in Miami. It was there that the season would end on both a sad and shameful note.

It was in Florida where a sad reality check of the times emerged, as black players that had been accepted on the west coast found things to be far different in the south, where deep-seeded institutionalized bigotry was status quo. Robinson and Williams had carried the team for three years with their stellar play, vital pieces in Coach McEwan’s attack, particularly with Kitzmiller now out of commission they were to play prominent roles in the game against Florida.

The University of Florida however had a strict policy in place, no black athletes allowed. The Gators refused to play the game if Oregon was to field any black players, forcing Bobby Robinson and Charles Williams to skip their final game for the University of Oregon being left back at home. The Eugene community and UO administration were outraged, yet relented and reluctantly agreed to the callous request.

Without Robinson and Williams, Oregon was inept against the Gators, losing 20-6, leaving Oregon without a post-season bowl to attend. The Florida heat may have had something to do with Oregon’s sub-par performance as well as the absence of Robinson and Williams, as many of the Oregon players chose to play the game with their jerseys off amidst the humidity of the deep south.

Not only would the Florida loss be the end of Robinson and Williams’ playing careers at Oregon, but it also marked the end of McEwan’s tenure. Following multiple clashes over forced restrictions on playing time for Robinson and Williams, with a year left on his contract the University of Oregon bought out the remainder of his deal, choosing to bring in C.W. Spears from Minnesota.

Under Spears in 1930 Kitzmiller would earn 2nd team All-American status and tackle George Christensen would be named a 1st team All-American, only the second Oregon player to earn such distinction. Kitzmiller was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1969.

Following the 1929 season, Bobby Robinson was named third team all-Pacific Coast Conference halfback. While Bobby Robinson’s football days were done, he continued to compete in track & field and other sports, including a first place tie for the conference championship in the pole vault. He had a stellar career competing in track & field in Canada, before eventually settling in Los Angeles where he became a social activist in his later years. Charles Williams meanwhile returned to Portland where he married, and worked in a warehouse.

Whatever feats of athletic prowess Robert “Bobby” Robinson and Charles Williams accomplished on the field, it was just as important to the future of the University of Oregon how they carried themselves off of it. Coach McEwan referred to Charles Williams as “the toughest man I ever met,” for his strength on and off the field amidst adverse times. Their efforts at Oregon paved the way so that others too may follow, unimpeded by societal barricades aimed at keeping minorities from being on a level playing field with their white counterparts.

Bobby Robinson at a 1930 golf tournament. From left to right: Wally Boyle, unidentified, Art Schoeni, Bobby Robinson, Faulkner Short.

Their efforts paved the way for other black athletes to shine at the University of Oregon.

In 1931 Oregon was led by “The Midnight Express,” a trio of running backs that included Joe Lillard, one of the last black players in the NFL prior to the 1946 Rams, contributing for two seasons with the Chicago Cardinals prior to the ban on African-American players following the 1933 season. Lillard also played on the Oregon basketball and baseball teams.

In the 1940s Bob Reynolds played for Oregon in 1942, before leaving to fight in World War II, and upon the end of the war returned to Eugene to continue his football career for the ’45 and ’46 seasons. His nephew Walt S. Reynolds would also attend Oregon, playing three sports as a Duck; first as Dan Fouts backup QB on the 1969 freshmen team, then a 4-year letterman at Oregon as a guard for the basketball team and playing two seasons of baseball.

In 1948 and 1949, Woodley Lewis, a transfer from Los Angeles City College, would shine as Oregon’s star halfback. In 1949 the Ducks would play in the Cotton Bowl, with Woodley Lewis named team MVP.

In 1950, Lewis became the first African-American selected in the NFL draft. Lewis remains Oregon’s single-season and career record-holder in kickoff return average (43.2 and 34.1 yards per attempt respectively), and holds the records for the longest punt and kickoff returns in school history.

Many others would follow, as by the 50s seeing black athletes donning the yellow and green of Oregon was common. Willie West and Alden Kimbrough among others would help lead the efforts of the scrappy 1957-58 Oregon Ducks as they fought valiantly with #1-ranked Ohio State in the Rose Bowl, losing 10-7.

A decade later Bobby Moore (now Ahmad Rashad) would become a star at Oregon, eventually becoming the third overall selection in the NFL draft in 1973. In 1979-80, quarterback Reggie Ogburn would be the one-man human highlight reel, leading Oregon in passing and rushing both seasons.

The University of Oregon may not have been the very first school to openly embrace student-athletes regardless of ethnicity, but starting in 1926 it emerged as one of the leaders in the path towards equality. While some parts of the country lagged far behind marred in racism and unfair stereotypes about what black athletes could and could not do, African-Americans and other minorities were welcomed to come participate on an even level of competition at Oregon as student-athletes, bucking pre-Civil Rights Movement socio-economic trends. That proud aspect associated today with Oregon, of embracing equality and the spirit of individuality, was a path set in motion long ago thanks in large part to Bobby Robinson and Charles Williams.

Today University of Oregon athletics feature student-athletes of all discernible backgrounds. Athletes come from all over the globe to train in Tracktown U.S.A., to compete at Hayward Field in the Prefontaine Classic and other events, while the athletic program benefits from the talents of athletes of all ethnicities, creeds, and other differences once thought unacceptable to be mixed on campuses across the country.

At the University of Oregon, truly the only colors that matter today are green and yellow…and black, and steel matte, and grellow; and whatever other fluorescent rainbow uniform combinations may be unleashed in the future. Oregon is a place of innovation and forward-thinking, spurred by the sense of family within the program and universal acceptance in the community. For the present and future grand accomplishments to come at the U of O, we all owe a debt of gratitude to those who have come before, in particular the incredible talents and groundbreaking courage displayed by Bobby Robinson and Charles Williams.

Photos provided courtesy of University of Oregon Knight Library special collections

Related Articles:

These are articles where the writer left and for some reason did not want his/her name on it any longer or went sideways of our rules–so we assigned it to “staff.” We are grateful to all the writers who contributed to the site through these articles.