Sitting in purgatory, more commonly known as Bay Area traffic, I had ample time to reflect on the bumper sticker on the car now parked in front of me. “Remember who you wanted to be?” it asked. That’s actually an incredibly loaded question for a weekday. Astronaut … poet … rock star, for most people. The list is extensive. That is unless your name is Dana Dean Altman.

Bay Area traffic blues.

Photo credit: internationaldailymagazine

If there is truly a child inside every man, then the child inside of Dana Altman has to be Opie Taylor. Because every time I see Altman standing on the Oregon bench – tall, sandy-haired, replete in a starched white shirt and conservative tie (never the full suit) – I catch a glimpse of little Opie, “all grownsed up” (thank you Vince Vaughn).

I mean come on, it’s right out of central casting. In the 1960s you couldn’t get a better representation of small-town, down-home Middle America than the ever-thoughtful, always trustworthy Opie. He was the one and true son of Mayberry, a fictional town as homespun and whimsical as Neverland or Oz.

Dana Altman is following in the footsteps of Oregon’s Hall of Fame Coach Howard Hobson.

Photo Credit: Gary Breedlove

Opie playing a young Dana Altman.l

Photo credit: youtube

I might be wrong, but I’m going to bet that growing up and attending high school in Wilber, Nebraska, (population 1,870), as Altman did during that same period, may not have been all that different.

I once drove through that part of the heartland, heading from east to west. It’s a landscape of small Midwestern towns, of hardwood trees, grain silos and open skies, separated by miles and miles of wheat and corn.

Nestled along the banks of the Big Blue River, Wilber is one of those towns. You want city? You’ve got to hop in the car and drive 15 miles or so south to Beatrice, population 12,000. Beautiful.

Altman grew up tall and lanky, an Eagle Scout and two-sport star at Wilber High, before attending and playing basketball at Southeast Community College, only a few miles up the road. He finished his playing career and graduated magna cum laude from Eastern New Mexico with a degree in business (he later obtained his M.B.A.).

By all accounts, Altman was a solid player. But what set him apart, and what coaches recognized from very early on, was that he had an exceptional basketball mind, to the point where he became the de facto assistant coach on his college team, even while he was still playing.

A bit of Nebraska paradise

Photo credit: Michael Peterson

Perhaps this rare early maturity, this ability to gain almost immediate trust from peers and communicate across gaps in age and background should not come as a big surprise.

In 2010 Baylor University completed a study of Eagle Scouts and how they differ from the general population. How they excel in areas such as goal orientation, work ethic, planning and communication.

But what’s really interesting is how Eagle Scouts tested significantly higher in skills that measured morality, tolerance and respect for diversity. Taking a closer look at this skill set, it’s amazing how seamlessly they relate to coaching.

Only a very small percentage (2-3 percent) of all who participate in scouting attain the level of Eagle Scout. Altman was one of those few, because concepts such as morality, tolerance and work ethic were not just words on a page to him, they were hard-wired into his being, the very fabric of his Midwestern upbringing. It was these very same core values, ones that defined him as a young man, that would later define him as a coach.

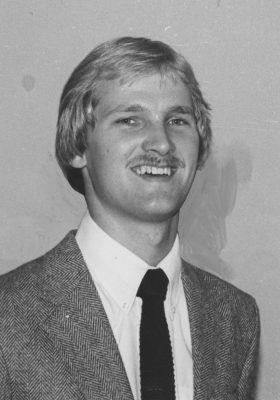

Coach Altman at age 24 at South East Community College

Photo credit: Oklahoma World Herald

At the age of 24, barely older than some of his players, Altman accepted his first head-coaching job back at Southeast C.C. Despite his young age, players on that team immediately accepted, and more importantly responded to him as their head coach.

They spoke of his maturity, his competitiveness, and his vast knowledge of the game. He preached up-tempo offensive and pressure defense, effort and team discipline, all the while walking that ever-so-fine line between friend and coach.

That team went 29-6 and finished 3rd in the junior college national tournament. Altman was named Nebraska College Coach of the Year, all of this in his first year as a head coach.

The fuse was now lit, the trajectory and life course locked in. Even back then, at such a young age, friends and players spoke of how Altman always knew who he was, and, I’m guessing, who he was going to be. An admitted perfectionist, his coaching style reflected his personality. Meticulous scouting and preparation flowed into detailed practices that ran as long as they took until the desired result was achieved.

As a player he took every loss personally, and that trait only became more pronounced as a coach. The energy that wouldn’t allow him to take a seat during games, wouldn’t allow him to sleep after losses. He came up with a simple solution to the problem, just don’t lose.

Nebraska community college basketball drills.

Photo credit: Stack.com

Coaching junior college basketball for the next three years (Moberly Junior College), Altman’s teams amassed an incredible record of 98-14. With the two-year-and-done routine commonplace at that level, Altman became adept at cobbling together teams with players of diverse backgrounds from all parts of the country and quickly molding those varied parts into a cohesive unit.

Sound familiar Duck fans? That skill served him well as he climbed the coaching ladder into Division I ball.

Hitching a ride with one of his junior college recruits (two-time Olympian and future Hall of Famer Mitch Richmond) to Kansas State, Altman spent a brief time as an assistant before landing his first big time college head-coaching job, first with Marshall, then back at Kansas State.

Nebraskan to the core, it was destined that he would once again coach in his home state, and in 1994 he became the head man at Creighton. For the next 16 years, Altman’s name and Creighton basketball became synonymous, as he built that mid-major into a perennial top-25 program.

Given his deep Midwestern roots it was a surprise to many that he answered Oregon’s call in 2010 and left the heartland for the Willamette Valley.

By all accounts he wasn’t the Ducks’ first or even second choice to take over the reins from Ernie Kent. Given his unprecedented success at Oregon, his Ducks teams having never won fewer than 20 games in any of his seven seasons, that’s a rather scary thought.

Crowned in Yellow & Lemon wins the Midwest Regional.

Photo credit: Ark La Tex

And if Altman’s story were purely fiction, if it were all Opie and Mayberry, we would most likely end it here – our hero and his lovely bride of 30-plus years, Reva (they married as college sweethearts), basking in the eternal glow and appreciation of Oregon fans everywhere. A job well done for finally climbing the mountain and delivering Oregon to the promised land of the Final Four.

But fiction is not reality and life’s journey is never that clear. In life, paths are lost, character is tested and self-doubt becomes a familiar companion. Toward the end of the 2014 basketball season the Oregon program went off the rails. We’ll never know the full story of what happened that night between three Oregon basketball players and a young UO coed, and this article will not try to answer questions on events that will most likely never be fully answered.

Suffice it to say that there was a night where horrible decisions were made and lives were forever changed. The three players, never formally charged, were dismissed from the team and the University made a financial settlement out of court with the young woman.

For Altman, still adjusting to his new surroundings at Oregon, the fall from grace was precipitous. Operating under the guidance of the Eugene Police Department, he was instructed to not dismiss the players in question while their investigation was ongoing. The perception of a look-the-other-way program was swift, and combined with other off-court player infractions (shoplifting, snowball fights, etc.), Oregon was quickly gaining the reputation as an ‘Outlaw” program.

A very trying time for Coach Altman.

Photo credit Craig Strobeck

Altman was reeling. In more than 25 years of coaching, he had never faced a storm quite like this. A now-infamous article by The Oregonian’s John Canzano led the charge for Altman to resign or be fired. It was indeed an ugly time to be a fan of Ducks basketball. That was only three years ago.

Reflecting back I think people were looking for Dana Altman to be something that he wasn’t. They wanted mercurial, not measured, they wanted immediate, not methodical.

Quiet, resolute, solid, Altman is a man of deep religious values and introspection, and has never been one to seek out or be comfortable in the spotlight. But while personally devastated by the event and its aftermath, not even the deepest crisis of his coaching career would alter his essential core. Perhaps Kipling said it best … “If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs …”

Thankfully, Altman was able to keep his job, along with his head. And he did what he’s always done after a major loss – he followed deep reflection and introspection with rigorous work.

In the spring of 2014, Altman set about implementing changes to repair the damage to himself and his program, and to put Oregon back on the rails. He changed his players’ living arrangements, assistant coach monitoring responsibilities and his own recruiting practices.

Amidst the carnage, in quite possibly the most difficult recruiting year of his life, Altman brought in, among others, Dillon Brooks, Casey Benson, and Jordan Bell, foundation pieces to this year’s Final Four team. Master chemist that he is, and all the time using honored team-building skills first honed back in junior college, Altman blended transfers, recruits and some resolute stalwarts who stayed with the program, into a team that went 26–10 and went to the second round of the NCAA tournament.

Upon the completion of the 2014/15 season he was named Pac-12 Coach of the Year for the second time, an astonishing rebound and, for my money, the most impressive coaching performance of his career.

And it would get even better …

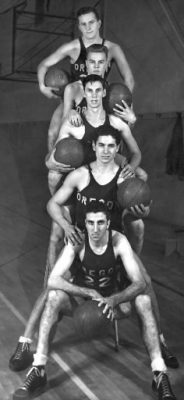

Oregon’s 1939 “Tall Firs”

Photo credit: BBall Oldtimers

Seven deep and not playing their best ball, dazzled by the bright lights on the biggest of stages, the Ducks managed to scrap with the mighty North Carolina Tar Heels deep into the dying seconds of their NCAA semifinal contest. It came down to a single point, a single rebound, a single possession. I’m weak on Shakespeare, but I’m pretty sure it was Richard III who said, “a rebound, a rebound, my kingdom for a rebound.” Son of a … .

So yes, I prefer my characters nuanced, my protagonist’s story complex. It’s closer to what I find life to truly be and what all of us have experienced and can relate to in this existence.

I also prefer my endings to be happy and returning the University of Oregon Ducks to the Final Four after 79 years and getting us a seat at the Big Table certainly qualifies.

Somewhere, Laddie Gale and the rest of the 1939 “Tall Firs” are raising their glasses high. So tonight I’ll raise mine, as well, and add a silent toast: “Coach, native son of Nebraska though you be, I think Oregon shares you now.”

Marc Burton

San Francisco Bay Area

Top photo credit: Mayberry Wiki

Related Articles:

FishDuck Foaming Over Upside of 2026 Diamond Ducks

Unbelievable...Same SEC Stuff, Different Day

Why Oregon Football Always Belongs in the National Conversation

The B1G Won the 2026 Coaching Carousel...Big-Time!

Continuity? Lanning's Hiring Success is Put to the Test

Why Whether Dyer Was Down or Not...Doesn't Matter

These are articles where the writer left and for some reason did not want his/her name on it any longer or went sideways of our rules–so we assigned it to “staff.” We are grateful to all the writers who contributed to the site through these articles.