About a year ago, Cole Irvin had a decision to make: play for the Ducks or go to the minor leagues. The left-handed starting pitcher had already committed to Oregon, but when the MLB Draft rolled around in June, the Toronto Blue Jays decided to select him in the 29th round.

We all know what happened next. Irvin rejected pro ball to become a Duck, and he has been one of the best pitchers in the Pac-12 this season.

So far, Irvin has a 2.64 ERA, a microscopic walk rate, and has pitched a team-high 92 innings. He’s been especially good in the second half of the season, as evidenced by his two PAC-12 Player of Week awards in the past month and a half.

Yet for such an accomplished, highly touted young pitcher, his stuff is merely good, not great. This would be a concern if he wasn’t so brilliant in the most crucial area of pitching, command.

In fact, his command makes him electrifying to watch because he’ll throw any of his pitches in any count, always coming close to his target.

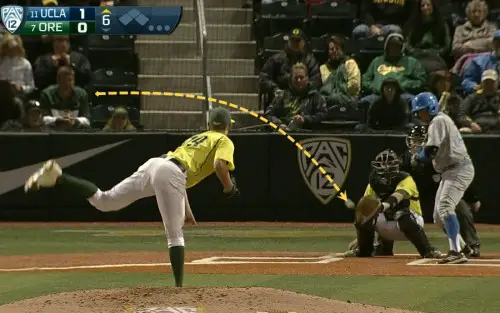

Irvin’s curveball is the best example of his pin-point accuracy:

There are two key points about these pitches: 1) They’re on the first pitch, 2) They’re strikes. Breaking balls are often the hardest pitch for pitchers to control, so in order to avoid falling behind in the count (more balls than strikes), pitchers will generally throw fastballs.

Irvin has no fear of falling behind 1-0 when he throws his curveball, and as illustrated by the shots above, he can keep it in the strike zone – on the corners, to boot.

That being said, a 0-0 count with nobody on base is a very low-leverage situation. Even if those curveballs missed, 1-0 counts wouldn’t be the end of the world. However, Irvin doesn’t suddenly stop throwing breaking balls when runners are on base:

Like the images before, the count is 0-0 and there are no outs in this situation, but there are runners on base and they’re both in scoring position. Pitchers with little control and command of their curveball would probably throw a fastball in this situation in order to avoid falling behind in the count or throwing a run-scoring wild pitch. Not Irvin, who tosses a curveball in for a strike like he’s playing Frisbee with his buddies.

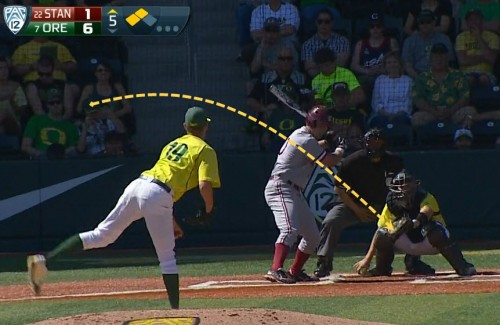

Irvin has shown just as much confidence with his other primary off-speed pitch, his changeup:

At 2-0, this is a “hitter’s” count. Like many batters would in this situation, Stanford’s Brian Ragira looks like he’s expecting a fastball in the strike zone, but Irvin throws a changeup low and outside, causing Ragira to take a goofy-looking swing.

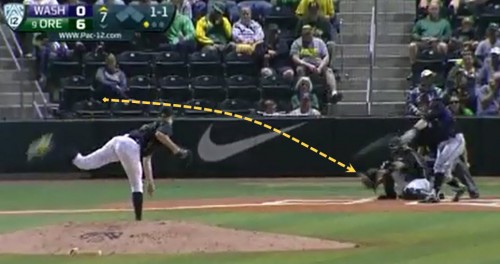

Irvin throws a similar changeup here to Washington’s Ryan Wiggins, resulting in the same type of swing and miss. 1-1 isn’t considered a hitter’s count, but this shot still illustrates how confident Irvin is in his changeup and how nasty the pitch is.

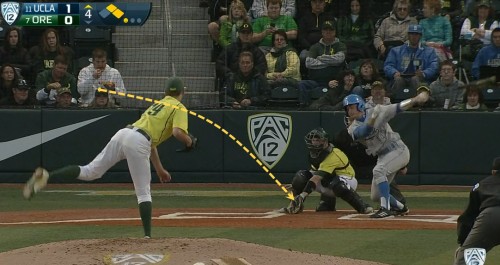

This looks almost identical to the last two screen shots. Irvin throws a first-pitch changeup to UCLA’s Shane Zeile, who suffers the same fate Ragira and Wiggins do; expecting a fastball, getting a changeup, and looking like a fool.

Irvin still throws his fastball more than his off-speed stuff, which is true of basically every pitcher not named R.A. Dickey. Still, Irvin has proven that he is comfortable throwing anything no matter what the situation is, which is especially important for someone who only throws around 87-90 miles per hour with his fastball. Hitters become much more tentative if they can’t predict the next pitch, which results in a lot of weak contact. Watch Irvin’s next start and you’ll likely see an unusual amount of slowly hit ground balls from the opposing lineup.

Irvin wasn’t a bad pitcher in the first half of the season, but coach George Horton did notice something that was holding him back a bit.

“When he got ahead, he threw too many strikes,” Horton said after Irvin’s March 10 start against Vanderbilt.

Throwing “too many strikes” might sound like a contradiction in terms, but there is a lot of truth to that statement, especially when the pitcher has count leverage. If a hitter is behind 0-2 or 1-2, he often becomes more aggressive because he can’t afford to take a strike. The pitcher is doing the hitter a favor if he throws anything resembling a good pitch to hit, so coaches often tell their pitchers to throw outside the strike zone.

If we look closer, however, there’s strategy behind these pitches, even if they aren’t close to the zone. Take this, for instance:

The fastball here is close enough to tempt the hitter into swinging, but it’s too high for the hitter to realistically do any damage.

It also raises the hitter’s eye line. Pitchers generally don’t throw higher than the hitter’s belt, so by throwing a fastball as high as the one above, the hitter’s eyes suddenly have to adapt to a new level of vision. Irvin’s next pitch was a sinking fastball about knee-high, resulting in a swing and a miss. For the hitter, that at bat was like sitting in a bright, windowless room all day when the power suddenly turns off, only for it to turn back on five seconds later.

Pitchers sometimes take the exact opposite approach in favorable counts:

This curveball in the dirt (well, turf, if we’re being literal) essentially serves the same functions as the high fastball; it changes the hitter’s eye level, it’s a terrible pitch to hit, yet it’s close enough to tempt the hitter into chasing.

Irvin said it best after the Vanderbilt game – ”Hitters can get themselves out.” Just look at those three screenshots of Irvin’s changeups. None of those pitches ended up being close to the strike zone, yet hitters swung at them each time.

This is why Irvin’s command is so important. When hitters expect strikes, they’ll be much more likely to swing at pitches like that curveball in the dirt. The pitches don’t even have to be that close, just close enough to get the hitter thinking, ”this might be in the zone.”

Pitchers’ jobs are to make opposing batters as uncomfortable as possible. Irvin forces hitters to be aggressive because he throws a ton of strikes, but he also forces them to be patient because he’s not afraid to throw a ball. Oh, and he’ll throw three pitches with equal confidence… in any count. What’s more incredible is that he’s likely going to improve.

Related Articles:

Seven Offensive Coordinator Candidates for the Oregon Ducks

Five Candidates to Replace OC Marcus Arroyo

Coach Jim Mastro: The Perception, and the Truth

Has Oregon Turned the Corner on Offense?

Ducks, Taggart Punish Beavers; Earn Bowling Trip

Textbook Defense, Herbert's Return Energize Duck Victory; Civil War Next

Victor is a senior at the University of Oregon, majoring in journalism and minoring in psychology. Victor was born and raised in San Francisco, CA. He is a fan of the San Francisco Giants, San Francisco 49ers, and Golden State Warriors and has naturally fallen in love with the Ducks since he became a UO student. He currently works for the UO campus radio station 88.1 KWVA as a news and sports contributor and hopes to one day become a professional sports reporter. While he loves several sports, baseball has always been his greatest passion.